Richard Tapper Cadbury’s second son, Joel, was able to fulfil his father’s own dream of seeking his fortune in America, and set sail in 1815 at the age of sixteen. The stormy Atlantic crossing took eighty days in high winds and rough seas that washed a man overboard and prompted seasoned sailors to say they had never seen such a sea. Joel eventually settled in Philadelphia, and became a cotton goods manufacturer. He had a family of eleven children, and established a large branch of Quakers on the east coast of America.

Richard’s third son, John – the father of Richard and George – born in 1801 above his father’s draper’s shop, was destined to have a very different fate. According to an account handed down through generations, John’s far-sighted father, having passed on his business to his oldest son, Benjamin, asked John to investigate the new colonial market in Mincing Lane, London. He was curious about a new commodity, the cocoa bean, which was arriving from the New World.

Today, among the gleaming black façades of City office blocks, there is little to give away Mincing Lane’s colourful past. The only hint of its nineteenth-century purpose survives in the name of a building halfway down the street: Plantation House. But when John Cadbury visited in the 1820s, it was a teeming market where colonial brokers met to trade in commodities from Britain’s growing empire. There were sale rooms where frenetic auctions were taking place for tea, sugar, coffee, jute, gums, waxes, vegetable oils, spices and cocoa. Prices and details of business were written on a blackboard, and samples of goods from warehouses in the docks along the nearby Thames were on display. They included the cocoa bean, or ‘nib’, from South America, which looked like a huge chocolate-coloured almond, still dusted with the dried pulp that surrounded it in the cocoa pod, and baked by the tropical sun.

At a time when cocoa was purchased primarily to produce a novelty drink for the rich, John’s mission was to ascertain whether there might be a future in this unpromising black bean.

John Cadbury, like his father before him, had set out to learn his trade at a young age as an apprentice. In 1816, aged fifteen and proudly dressed in the best-quality cloth from the family’s draper’s shop, he took the coach journey to Leeds, where he was apprenticed to a Quaker tea dealer. It appears he made a good impression. His aunt, Sarah Cash, who visited the following year, declared, ‘John is grown a fine youth, he possesses a fine open countenance, is vigorous of mind and body and desires to render himself useful.’ Others commented that the plain Quaker boy, soberly dressed in dark colours, stood out next to the rough Yorkshire boys. It seems the owners were soon content to leave the care of their tea business with John when they had to travel, and he was rewarded on his departure after seven years with a fine encyclopaedia.

John went to London to be apprenticed at the teahouse of Sanderson Fox and Company. While in London he went to see the warehouses of the East India Company, and watched the sale of commodities such as coffee and cocoa. He wrote to his father that he was convinced that there was potential in the exotic new bean, although he was not yet clear what that potential was.

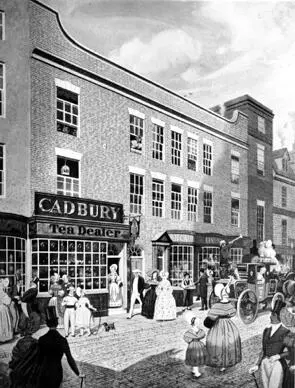

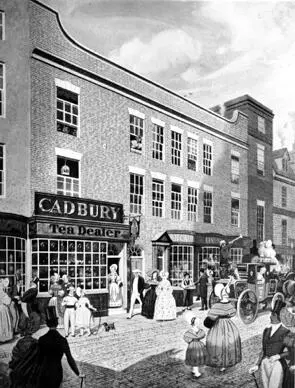

In 1824 the twenty-three-year-old John returned to Birmingham and set up a tea and coffee shop of his own on Bull Street, next door to his brother Benjamin’s draper’s shop. His father lent him a small sum of money and said he must ‘sink or swim’, as there were no further funds. John proudly announced the opening of his shop in the local paper, Aris’s Birmingham Gazette , on 1 March. After setting out his considerable experience ‘examining the teas in the East India Company’s warehouses in London’, he drew the public’s attention to something new: a substance ‘affording a most nutritious beverage for breakfast . . . Cocoa Nibs prepared by himself’.

John Cadbury’s tea and cocoa shop in Bull Street, Birmingham, in 1824.

John Cadbury took advantage of the latest ideas to draw business to his shop, starting with the window. While most other shops had green-ribbed windows, John’s had innumerable small squares of plate glass, each set in a mahogany frame, which it was said he polished himself each morning. This alone was such a novelty that people would come to see it from miles around. On peering through the glass, prospective customers would be intrigued to see a touch of the Orient in the heart of smoky Birmingham. The many inviting varieties of tea, coffee and chocolate were displayed amongst handsome blue Chinese vases, Asian figurines and ornamental chests. Weaving his way through all this exotica was a Chinese worker in Oriental dress. Those who ventured inside were greeted by the rich aroma of coffee and chocolate; John ground the cocoa beans himself in the back of the shop with mortar and pestle. Word of John Cadbury’s quality teas and coffees soon spread amongst the wealthiest and best-known families in Birmingham: his customers included the Lloyds, Boultons, Watts, Galtons and others.

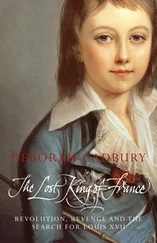

Meanwhile, through the Quaker network, John met Candia Barrow of Lancaster. The Barrows and the Cadburys had already developed very close ties through marriage. In 1823 John’s older sister Sarah had married Candia Barrow’s older brother. This was followed in 1829 by the marriage of John’s older brother Benjamin to Candia’s cousin, Candia Wadkin. So in June 1832, when John married Candia Barrow, it was the third marriage in a generation to link the two Quaker families. It proved to be a very happy union.

As John’s shop prospered, he could see for himself the growing demand for cocoa nibs. He took advantage of the large cellars under the shop to experiment with different recipes, and created several successful cocoa powder drinks. So confident was he of the future of this nutritious and wholesome drink that he decided to take a further step: into manufacturing.

In 1831, John rented a four-storey building in Crooked Lane, a winding back street at the bottom of Bull Street, and began to test produce cocoa on a larger scale. The idea of using machines to help process food was in its infancy, but to help him with the roasting and pressing of beans he installed a steam engine, which evidently was a great family novelty. According to his admiring aunt Sarah Cash, everyone in the family ‘had thoroughly seen John’s steam engine’. After ten years he had developed a wide variety of different types of cocoa for his shop: flakes, powders, cakes, and even the roasted and crushed nibs themselves.

Candia at the time of her marriage to John Cadbury.

Meanwhile, Candia and John started a family, and moved to a house with a garden in the rural district of Edgbaston. Their first son, John, suffered intermittently from poor health. Richard Cadbury, their second child, was born on 29 August 1835, and was followed by a sister, Maria, and then George, born on 19 November 1839. The arrival of two more sons, Edward and Henry, would complete the family.

To the boys’ delight their parents placed a strong emphasis on the enjoyment of an outdoor life. Their house had a square lawn, recalled Maria. ‘Our father measured it round, 21 times for a mile, where we used to run, one after another, with our hoops before breakfast, seldom letting them drop before reaching the mile, and sometimes a mile and a half, which Richard generally did.’ Only then were they allowed in for breakfast, ‘basins of milk . . . with delicious cream on top and toast to dip in’. After this early-morning ritual, John set off to work. ‘I can picture his rosy countenance full of vigour,’ says Maria, ‘his Quaker dress very neat with its clean white cravat.’

Читать дальше