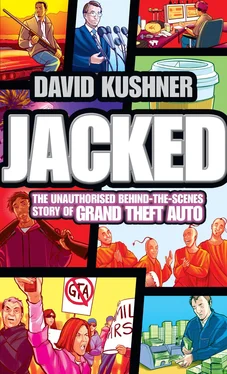

This wasn’t just fun and games, though. DMA exemplified the DIY spirit of the times: all you needed was a computer and a dream. Jones was on a mission to make games as cool and fast as his sports car. “We have three to five minutes to capture people,” as he once said. “I don’t care how great your game is, you have three to five minutes.” The edict worked again. Blood Money , billed as “the ultimate arcade game,” came out in 1989 and sold more than thirty thousand copies in two months. Jones felt elated. He was on his way.

In the competitive arena of game making, developers would compete to exploit the latest, greatest programming innovations. One day, a DMA programmer discovered how to animate as many as a hundred characters on screen at a time and made a demo for the team. Jones watched in awe as a line of tiny creatures stupidly marched to their deaths—smashed by a ten-ton weight or incinerated in the mouth of a gun. It was just the sort of dark Scottish humor that got everyone laughing. Let’s make a game out of that!

They called it Lemmings. The object was to save the creatures from dying. Jones’s crew devilishly dreamed up the most punishing fates for the little beasts: falling into holes, getting crushed by boulders, being incinerated in lakes of fire, or getting ripped to shreds by machines. To survive, you had to assign each creature a skill, from digging to climbing, building to bashing. With more than 120 scenes of zig-zagging creatures, the game didn’t only play—it teemed with life.

Lemmings was released on Valentine’s Day 1991 with a warning label: “We Are Not Responsible For: Loss of sanity. Loss of Sleep. Loss of Hair.” Lemmings became an immediate hit, selling fifty thousand copies on its first day alone. The game would go on to earn DMA more than £1.5 million, selling nearly 2 million copies worldwide. “To say that Lemmings took the computer gaming world by storm would be like saying that Henry Ford made a slight impact on the car market,” one reporter wrote.

Just twenty-five, Jones was one of the wealthiest—and most famous—game designers on the planet. His journey from drop-out to millionaire made him one of the industry’s biggest success stories. Ecstatic, he treated himself with his flashiest sports car yet, a Ferrari. Jones hit the road, speeding through the grim city past the gangs. If only there was a game in that.

“FUCK! Fuck! Fuck!”

It was just another day at DMA, and the biggest and most pungent coder on the team was having one of his tantrums again. Game making could be a mind-numbing craft—fashioning living worlds from abstract code—and sometimes this guy had to blow off steam. But as he stood banging his head against a wall and shouting, he saw a sprightly Japanese man beside him. “Oh, my God,” muttered another coder nearby, “that’s Miyamoto!”

Sure enough—it was him, Shigeru Miyamoto, the elfin genius of Nintendo, the inventor of Mario . Not long before, it would have been unthinkable that the biggest name in gaming would grace this little indie start-up in Dundee. Yet with the extraordinary success of Lemmings , Jones had scored a multimillion-pound contract to create two games for the Nintendo 64. “We think David Jones is one of the very few people in the world that are in the Spielberg category,” Howard Lincoln, now the president of Nintendo of America, told the press. Miyamoto, who took the screaming coder in stride, had come to experience the magic of DMA firsthand.

Flush with cash, DMA had moved to a 2,500-square-foot office in a mirrored, militaristic building inside the Dundee Technology Park on the west end of town. Jones invested £250,000 in outfitting their rooms with the best technology they could buy. DMA was said to have one of England’s biggest installations of refrigerator-size Silicon Graphics computers—so big that the minister of defense expressed security concerns. DMA needed the muscle power to bring Jones’s geekiest dream to life: “a living, breathing city.”

Virtual worlds were the stuff of science fiction but still not much of a reality in gaming. The appeal was obvious. Real life could be unpredictable and frustrating, but a synthetic world was something you could control. Jones had, as he put it, “a fascination with how alive and dynamic we could make the city from very little memory and very little processing speed. How could we make something living inside the machine?”

Jones set his team free to come up with their answers. Programmer Mike Dailly engineered a cityscape from a top-down point of view. Another DMAer coded dinosaurs running through the streets. Another replaced the dinosaurs with something cooler, more contemporary, and closer to the boss’s heart: cars. As Dailly watched the little virtual cars speed through the city, he thought, “We have something.”

Jones liked the concept of Cops and Robbers —casting players as the police out to bust the bad guys. “Cops and robbers is a natural rule set that everybody understands,” he said. “They know how to drive a car. They know what a gun does.” Thinking Cops and Robbers too generic a title, they renamed it Race ’n’ Chase instead.

Walking into DMA was like seeing a bunch of grown men playing with a Hot Wheels set—except on their PCs. From the overhead view onscreen, tiny pixilated cars cruised the streets, blips of people climbed onto buses and trains that stopped along their routes. Jones pushed for a more and more realistic simulation. Though cars could speed down the street, they had to stop at traffic lights that blinked from red to green. Jones watched gleefully as his little world teemed with life.

When a demo was ready, he took the game to a prospective publisher in London, BMG Interactive. The company wooed Jones heartily, eager to get into business with the UK’s boy wonder of gaming. Jones left with a deal to deliver four games over the next thirteen months for Sony, Sega, and Nintendo. He retained ownership and received an estimated £3.4 million. “They will treat computer companies in the same way that they treat their music companies,” Jones effused to a reporter.

Back in the BMG office, Sam and the others booted up Race ’n’ Chase. There was just one problem: the game kind of sucked.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.