LEVIATHAN

The Rise of Britain as a World Power

DAVID SCOTT

For Sarah

CONTENTS

Title Page LEVIATHAN The Rise of Britain as a World Power DAVID SCOTT

Dedication For Sarah

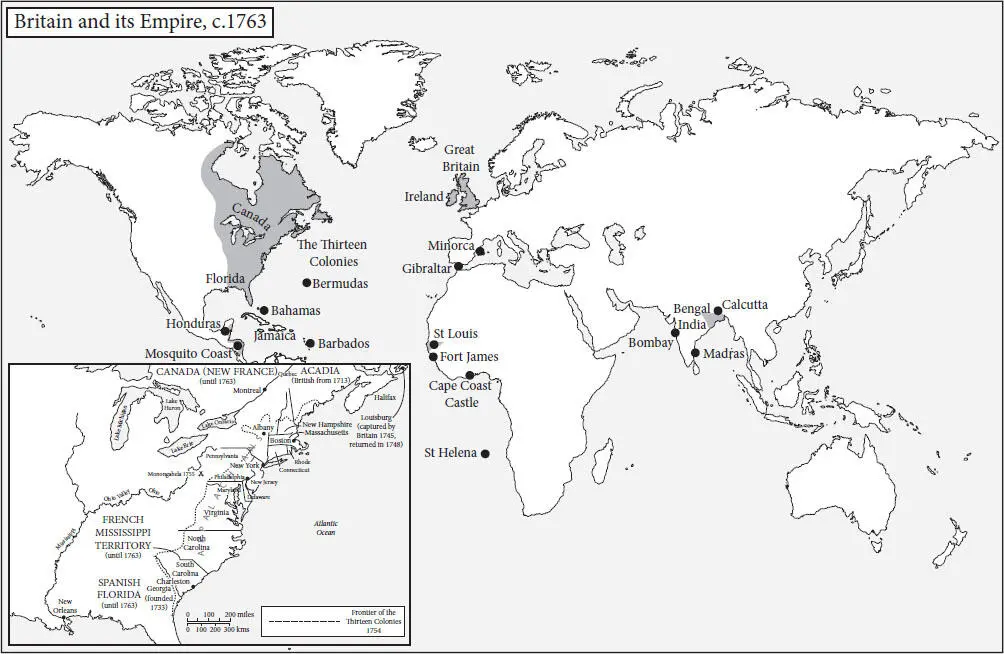

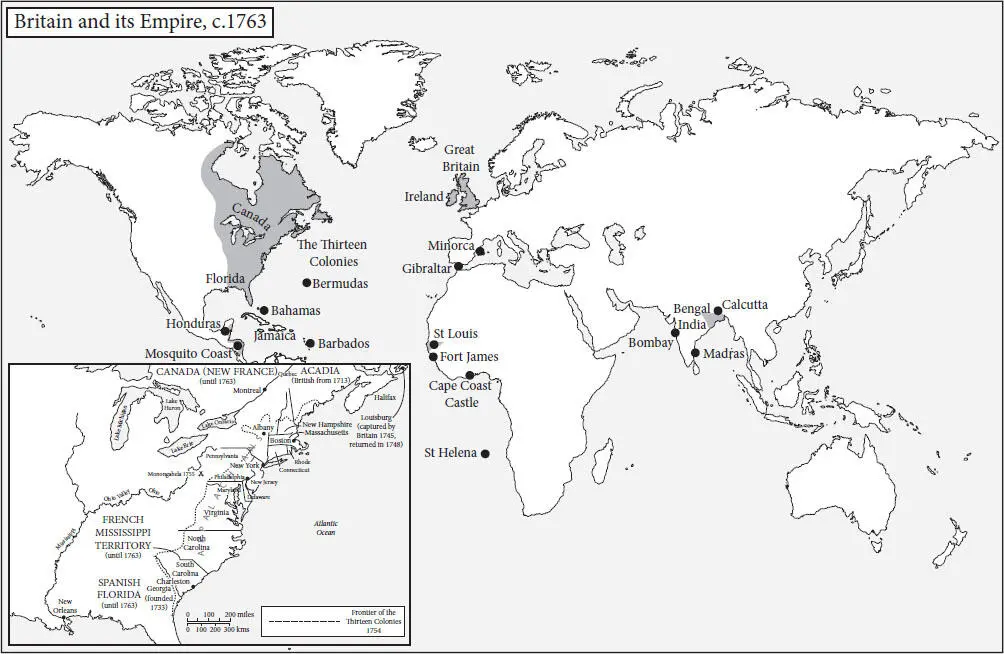

Maps

List of Illustrations

Preface

Lost Kingdoms, 1485–1526

The Protestant Cause, 1527–1603

Free Monarchy, 1603–37

Behemoth and Leviathan, 1637–60

The French Connection, 1660–1714

The Balance of Europe, 1714–54

Greatness of Empire

New World Order, 1754–83

Epilogue

Bibliography

Notes

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Also by David Scott

Copyright

About the Publisher

1. King Henry VII by unknown Flemish artist, 1505 ( © National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG 416 )

2. From The Image of Irelande by John Derrick, 1581 ( Courtesy Edinburgh University Library )

3. Armada playing cards, 1588 ( © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PU0214; PU0183; PU0181; PU0179 )

4. From Narratio regionum indicarum per Hispanos quosdam devastatarum verissima , 1598 ( Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de France. BNF C43328 )

5. Equestrian portrait of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck, 1633 ( Supplied by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2013. RCIN 405322 )

6. The Tiger by William Van de Velde the elder, c. 1681 ( © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PZ7304 )

7. View of the beheading of Charles I by unknown artist ( Private Collection / © Look and Learn / Peter Jackson Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library )

8. East India Company Ships at Deptford by unknown artist, c. 1660 ( © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. BHC1873 )

9. Duke’s plan of New York, 1664 ( © The British Library Board. Maps K.Top.CXXI.35. 008318 )

10. Engraving of London before the Great Fire by Pieter Hendricksz Schut, mid-17th century ( Courtesy Guildhall Library, City of London )

11. A Representation of the Popish Plot in 29 figures , c. 1678 ( © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 1871,1209.6512 )

12. The Common wealth ruleing with a standing Army , 1683 ( © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 1868,0808.3297)

13. Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme by William Hogarth, 1721

14. Excise in Triumph , c .1733 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

15. Idol-Worship or The Way to Preferment , 1740 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

16. The Lyon in Love , 1738 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

17. O the Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais) by William Hogarth, 1748, engraved by C. Mosley ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

18. Beer Street by William Hogarth, 1751

19. Gin Lane by William Hogarth, 1751

20. The Abolition of the Slave Trade by Isaac Cruikshank, 1792 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

21. Slaves processing sugar cane, c. 1667–71 ( © The British Library Board. C13236-18 )

22. Fort St George on the Coromandel Coast by Jan van Ryne, 1754 ( © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PU1845 )

23. The Ballance, or The American’s Triumphant , 1766 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

24. The Mob destroying & Setting Fire to the Kings Bench Prison & House of Correction in St Georges Fields , 1780 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

25. The Free-born Briton or A Perspective of Taxation , 1786 ( Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University )

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in future editions.

As Britain entered upon another global war with her old enemy France in the mid-1750s, the Royal Navy took timely delivery of the largest warship in the world. Built at Woolwich Dockyard and launched in 1756, the three-decker Royal George was a vast and intricately designed killing machine. Her construction had taken almost ten years and had consumed the wood of more than 5,000 oak and elm trees. She carried the tallest masts and the greatest spread of canvas of any ship in the navy. A crew of 867 men and boys was needed not only to sail her but also to work the hundred guns she mounted, which included twenty-eight massive ‘full cannon’ – the heaviest pieces of ordnance afloat – each firing a hull-smashing 42-pound ball. One broadside alone would throw over 1,000 lb weight of metal. Two broadsides were enough to sink the French 74-gun Superbe at the battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759 – the decisive naval engagement of the Seven Years War. Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar in 1805, named Victory to commemorate Britain’s ‘year of victories’ in 1759, would be modelled on the Royal George . Ships of the line such as these were the ultimate expression of Britain’s determination to stamp her naval superiority on every European rival, or indeed combination of rivals. The British would tolerate no balance of power at sea as they would on the Continent. But the Georgian navy served a larger purpose than engaging enemy fleets, for it kept the sea lanes open to the stream of goods to and from Britain that invigorated its industries, powered its economy towards the industrial revolution, and sustained the military expenditure of an altogether deadlier war machine: the British imperial state.

This book is partly about how and why the British and Irish peoples acquired the kind of state that could outdo the French and every other European power; that could build the Royal George and keep her, and hundreds more warships, at sea around the globe for months on end. It is a story that grew to encompass all of Britain and Ireland, and many other lands besides. But it began life in England. And here I must pause to make the familiar confession of English historians writing supposedly ‘British’ history. It was said of Georgian Britain’s longest-serving prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, that his political genius consisted in ‘understanding his own country, and his foible, inattention to every other country, by which it was impossible he could thoroughly understand his own’. 1Though I do not lay claim to Walpole’s superlative mastery of his art, there is no doubt that I share his foible. In my own defence I would argue that in writing a narrative history that covers (if only loosely) Britain and Ireland, it is almost impossible to avoid focusing on England. There is no ignoring the fact that England was the largest, the most populous and the most aggressive of the states that occupied the British Isles during the period covered by this book. Events in London and lowland England were bound to exert a greater influence over Scotland and Ireland than the other way round.

Читать дальше