Riddell’s successor was Major General Christopher Airy, the former commander of the army’s London District. Airy was hired only after being vetted, at Charles’s request, by Jimmy Savile. The TV personality, dressed in a silver tracksuit and sporting gold bangles, had met the candidate in Kensington Palace. ‘My job,’ explained Savile, ‘is to persuade you not to take the job. That’s what Prince Charles has asked me to do.’ Airy was bewildered. How, he wondered, had Savile – posthumously exposed as a serial predatory paedophile – induced the royals to allow him to make unannounced visits to Kensington Palace and be invited to Charles’s fortieth birthday party? The prince had even sent Savile a box of Havana cigars – a gift from Fidel Castro – with a note: ‘Nobody will ever know what you’ve done for this country, Jimmy. This is to go some way in thanking you.’ On his second interview, Airy was told by Savile that his appointment had been approved – but to expect lengthy waits whenever summoned by Charles.

The prince’s misjudgement about Savile coincided with his sympathy towards another sexual offender. He allowed Peter Ball, the Bishop of Lewes and Gloucester, to live in a property in Somerset provided by the Duchy of Cornwall despite the prelate’s admission that he had abused boys. The police, documents would later reveal, had cooperated with leaders of the Church of England, particularly George Carey, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to ‘prevent a scandal’, partly because Ball was ‘friendly with Prince Charles’. ‘I wish I could do more,’ Charles wrote to the paedophile in 1995, angry that Ball had not been re-appointed as bishop. ‘I feel so desperately strongly about the monstrous wrongs that have been done to you and the way you’ve been treated.’ Ball would be jailed in 2015.

These shameless relationships were unfamiliar to Airy. Within a year of his appointment, the ceremonial guardsman was reprimanded for suggesting to Charles that a forthcoming and unwelcome visit was ‘your duty, sir’.

‘Duty is what you do!’ Charles shouted at him. ‘Duty is what I live – an intolerable burden.’

Soon after, unaccustomed to his employer’s campaigns about poverty and his propensity for flying to hot climates for environmental summits, Airy was summarily fired – knifed, some speculated, by Aylard, his successor. Airy’s misery on his dismissal was later rekindled by gratuitously unpleasant comments about him in Jonathan Dimbleby’s book. Charles was a bad enemy. He carried grudges. That was the background to his disillusionment with Aylard. The fallout from the Dimbleby project exposed Aylard as hidebound by court procedure and unable to think outside the box. His lack of sympathy for new ideas increased the temptation for Charles to recruit Mark Bolland. He needed a saviour to relieve the agony of the previous fifteen years.

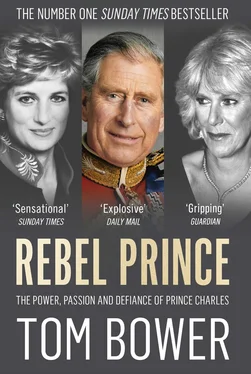

Ever since 1981, when a billion people around the world had watched his marriage to Diana, the battle of the Waleses had aroused global fascination. The accepted story of a selfish and cruel older man betraying a beloved icon was, Charles believed, the product of mismanagement by his advisers, although Charles conceded that even the best spin doctors would have been overwhelmed by the revelations about his private life.

Ken Stronach, a junior valet, had written a book about Charles’s affair with Camilla and was suspected of taking photographs of the royal bed; Wendy Berry, a Highgrove housekeeper, claimed to have witnessed not only Charles’s trysts with Camilla but Diana’s affair with her riding instructor, Major James Hewitt. But in November 1995 both scandals were eclipsed by Diana’s television interview on the BBC’s Panorama . After reciting her rehearsed criticism about the royal family, she admitted her adultery with Hewitt, and voiced her doubts about whether Charles would ever be king. The next moment, she accused Camilla of committing adultery with Charles from the first day of her own marriage, even intimating that her rival had slept with Charles the night before their wedding. Camilla, claimed Diana, was a permanent presence on their return from honeymoon: ‘There were three of us in the marriage, so it was a bit crowded.’

Britain was divided about where the guilt lay. The majority, especially women, blamed Charles. They believed the version written by Richard Kay, the Daily Mail journalist and Diana’s confidant: ‘I knew a girl of utter simplicity, even naïvety – frightened, uncertain and delightful company. She needed to be understood. She was not manipulative, but pushed to extremes of misery by the commentators. She just dreamed of being ordinary with a humdrum routine. “They don’t know how lucky they are,” she said about the millions of anonymous women envious of her looks and lifestyle.’

Visitors to Balmoral described a very different figure. Their accounts portrayed a manipulative woman intent on wrecking relationships, especially her own with Charles and with his mother. Some recalled an occasion when the queen, happily anticipating walking through the fields with her grandsons during an autumn pheasant shoot, was taken aback to be told that Diana had insisted instead that her children go swimming in a local public pool. Those same eyewitnesses blamed Diana for deceiving her staff about her covert cooperation with both the Morton book and the Panorama interview. They indicted royal advisers, especially Fellowes and Aylard, for failing to prevent the recurring crises.

Blame also fell on Camilla. Many times, her critics believed, she could have stood back to allow Charles and Diana to reconcile. Instead, she coldly pushed her rival aside. The climax was a confrontation between the two women sometime in 1989, when Diana arrived unexpectedly at a birthday party at Annabel Goldsmith’s house in Ham, near Richmond. Charles was with Diana, while both the Parker Bowleses were already there. As the rest of the room fell suddenly silent, Diana challenged Camilla to leave Charles alone. While acknowledging the hurt she was causing, Camilla controlled her fury and commented only about Diana’s ‘unacceptable behaviour in a private house’. The princess, she said was poorly placed to complain. While Camilla confined herself to a single, conventional relationship, Diana, she had been told by friends, was ‘working her way through the Life Guards’. Camilla’s intimates blamed the bruising encounter on Diana for creating ‘such a public scene’. Others accused Camilla of bitchiness.

Following Diana’s Panorama interview, the queen and Prince Philip – neither of whom Charles viewed as well-meaning advisers – told him that he could not rebuild his image nor dampen the controversy about the succession until he broke with Camilla. His misery deepened, and under pressure from his mother he agreed that he and Diana should divorce. Racked by self-doubt, he telephoned friends for reassurance, often talking well into the night. He mainly sought consolation in long calls with Fiona Shackleton and Camilla. ‘No one else,’ he later remarked, ‘was willing to lift a finger to help me.’ Less than twenty miles from Highgrove, damned as a marriage-wrecker, Camilla hid out in her house. Fuel was poured onto the flames by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who privately let it be known that, while he would crown Charles, he would not crown Camilla.

‘What more do I have to do?’ Charles tearfully asked Sandy Henney, a media adviser on his staff, and Aylard, her superior. ‘What’s the solution?’ He took the advice on offer, then made his decision: first, he ordered Aylard to announce that he had no intention of remarrying. Second, he followed Henney’s suggestion: ‘Push the PR to show “business as usual”. Project your work, sir.’

Читать дальше