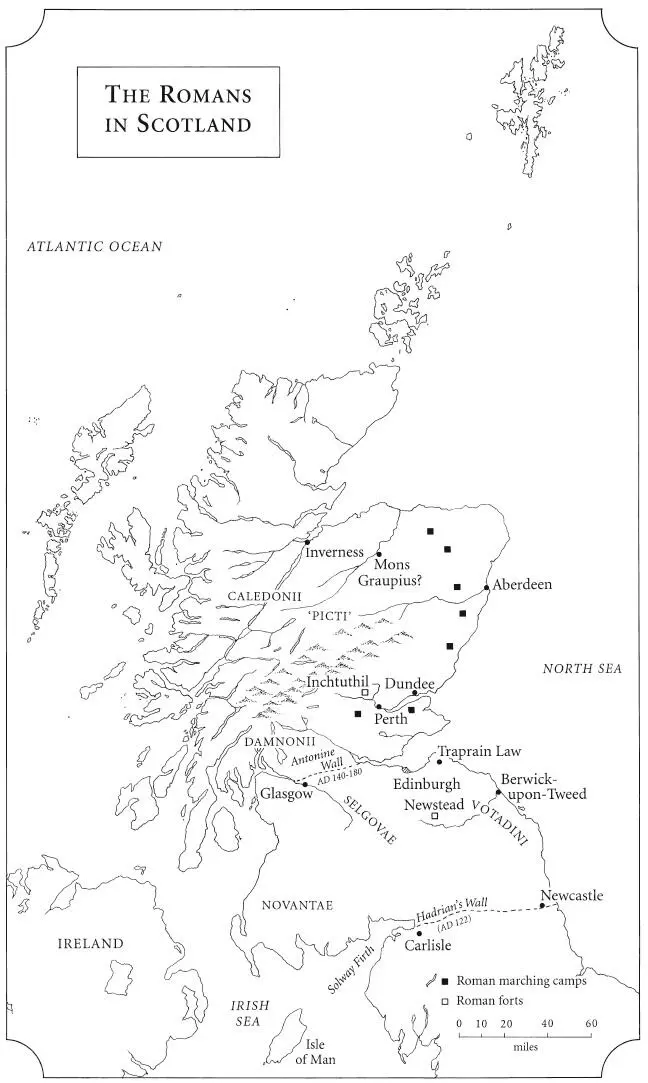

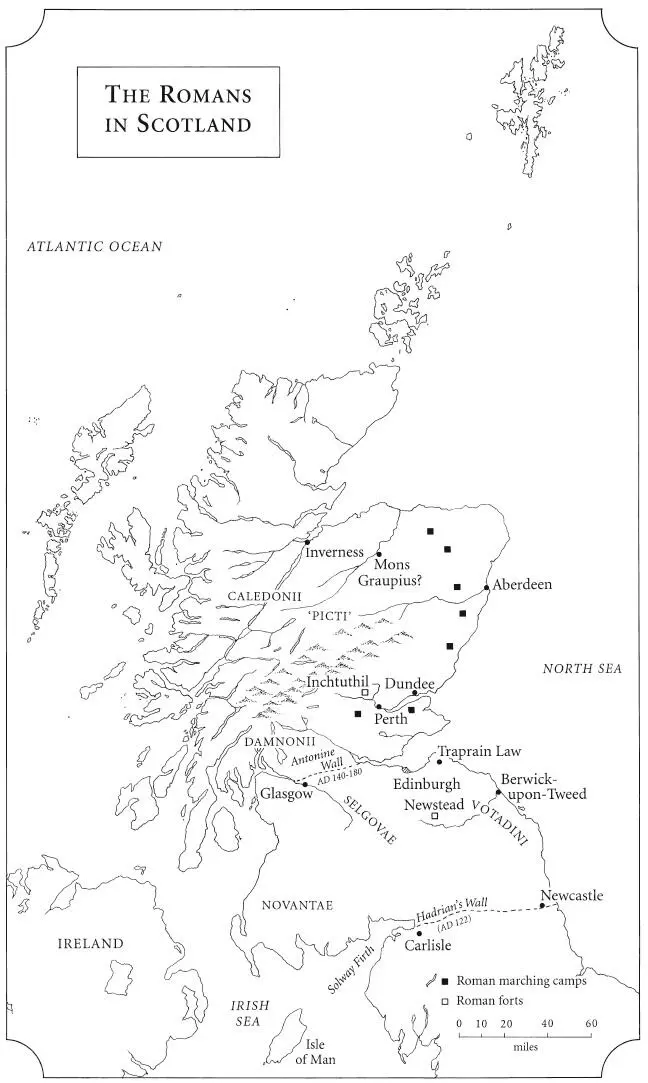

The location of ‘Mons Graupius’ has never been positively identified and has been the source of endless debate among archaeologists and historians. Some think the battle took place near Huntly on the slopes of a hill named Bennachie; others opt for somewhere closer to Stonehaven. The apparent similarity between ‘Graupius’ and ‘Grampian’ is intriguing, if inconclusive. It is also tempting to think that it may have been somewhere near Inverness – such as Culloden? – where in 1746, more than 1600 years later, another retreating ‘Caledonian’ army would be brought to battle and shattered by the superior firepower and discipline of a military machine from the south ( see Chapter 28). There, as at Mons Graupius, it was the last strategic point where a native leader could hold an army of Highland tribesmen together before they melted away to their winter straths and glens; there, as at Mons Graupius, defeat would leave what Tacitus called ‘a grim silence on every side, the hills deserted, homes smoking to heaven’.

The account by Tacitus of the battle of Mons Graupius makes compelling reading – particularly the noble rhetoric he put into the mouth of Calgacus (his name may be associated with the Gaelic calgath and mean ‘swordsman’) in his pre-battle speech, a ringing denunciation of Rome and its supposed civilisation, and the first recorded despairing cry of ‘Freedom!’ which would echo through the Highlands and Lowlands for centuries to come:

Former battles in which Rome was resisted left behind them hopes of help in us, because we, the noblest souls in all Britain, the dwellers in its inmost shrine, had never seen the shores of slavery and had preserved our very eyes from the desecration and the contamination of tyranny: here at the world’s end, on its last inch of liberty, we have lived unmolested to this day, in this sequestered nook of story.

But today the farthest bounds of Britain lie open; there are no other peoples beyond us; nothing but seas and cliffs and, more deadly even than these, the Romans, whose arrogance you shun in vain by obedience and self-restraint. Harriers of the world, when the earth has nothing left for their ever-plundering hands, they scour even the sea; if their enemy has wealth, they have greed; if he be poor, they are ambitious; neither East nor West can glut their appetite; alone of people on earth they passionately covet wealth and want alike.

To plunder, butcher, steal – these things they misname ‘empire’: they make a desert, and they call it peace.

The defeat was a crushing blow to the Caledonians and their northern neighbours, and a significant victory for the Romans; although beaten, however, the tribes were not broken. Agricola sent a reconnaissance fleet round the north coast to confirm that Britain was, indeed, an island. He may have felt the terrain so inhospitable as not to be worth the effort of military conquest; besides, he had already exceeded the normal five-year period as Governor. He contented himself with ordering the completion of a massive legionary fortress at Inchtuthil on the Tay, seven miles east of Dunkeld, with satellite forts blocking the way into the northern mountains. The following year he was recalled to Rome.

There was to be no Roman subjugation of the Highlands. The fortress at Inchtuthil did not last long. The Empire was in a constant state of flux, with troops required in hot-spots which would flare up here and there on the Continent. In AD 87, before it was even completed, the fortress was abandoned and systematically dismantled, its stores removed and its defences slighted. The Romans were in retreat, withdrawing gradually from all their forts and bases in Scotland. The native tribespeople helped them on their way with constant harassment. By 105 the Romans had withdrawn to a line between the Solway and the Tyne.

The tide turned again with the accession of Hadrian as Roman Emperor in 117. He visited Britain more than once, and in 122 he decided to consolidate the northern frontier with that great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, across the isthmus between the Solway and the Tyne. The Lowland tribes of Scotland were left in peace for a time – until 139, when a new Roman Governor (Quintus Lollius Urbicus) marched north from the wall in strength to reoccupy the territory Agricola had seized nearly fifty years earlier. It was then that he decided to consolidate his gains by building the Antonine Wall.

The Antonine Wall did not last very long either – only twenty years or so. After it was abandoned around 161 it was reoccupied, but only for a very short time, and by about 180 the Romans seem to have decided to pull back towards Hadrian’s Wall. There were occasional uprisings in the Lowlands, followed by severe punitive campaigns. But by 214 the Romans had finally withdrawn from Scotland, leaving Hadrian’s Wall as the ultimate frontier – the most impressive and enduring legacy of Roman rule in Britain. Scotland and its restless tribes were left to their own devices, held in check only by their domestic preoccupations and the Roman soldiery still garrisoning the fortlets of Hadrian’s Wall.

By now, however, the graffiti were really on the wall. And in 297, one of the most famous names of the north appears in the documentary record – the Picti, the warlike painted people who are still considered one of the great enigmas of early Scotland, with a kingdom which stretched from north of the Firth of Forth to the Moray Firth and beyond ( see Chapter 3).

They are mentioned as playing a key part in the great ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’ which, through accident or design, attacked Roman Britannia simultaneously from all sides in 367; the Angles and Saxons overwhelmed the coastal forts of the south and east, the Gaelic-speaking Scoti from Ireland came sweeping in across the Irish Sea, and the Picti overran Hadrian’s Wall from the north. From then on, the Roman hold on Britannia became more and more tenuous. They appointed three generals in quick succession in an attempt to save the province, and the defences were patched up again. But it was to no lasting avail. The Roman Empire was crumbling, and by 410 the last of the Roman army, along with the Roman administrators, had left Britain’s shores.

A century before they left, however, the Romans had given this enduring name to their main enemies in the north of Scotland: in the year 297 a Roman poet had referred to them as Picti (‘painted ones’). The name stuck, and ‘Picts’ became a generic term for the many ‘Caledonian’ tribes who lived north of the Forth – Clyde line and who thwarted the imperial ambitions of the Romans at their ultimate frontier.

Chapter 3 PICTS, SCOTS, BRITONS, ANGLES AND OTHERS

These people of the northern parts of Scotland, whom the Romans had not been able to subdue, were not one nation, but divided into two, called the Scots and the Picts; they often fought against each other, but they always joined together against the Romans, and the Britons who had been subdued by them.

TALES OF A GRANDFATHER , CHAPTER I

In the western outskirts of Inverness stands a massive hill crag, now engulfed in trees – Craig Phadrig. The summit of this crag was once the site of a great hill-fort, a mighty bastion of the early Pictish kings.

Not a lot of people know that it is there, or how to find it when they do know. It stands in the Kinmylies district, near Craig Phadrig Hospital; you drive up the steep, dead-end Leachkin Brae, which is not marked as leading to anywhere. Forest Enterprise has provided two woodland walks which meander through the forest at the lower levels of the crag; each has its own car park. To reach the summit of the crag, you use the second (upper) car park and follow the walkway from it. Then you leave its carefully graded surface, take a very deep breath, and embark on a fiercely steep scramble up, and up, and up.

Читать дальше