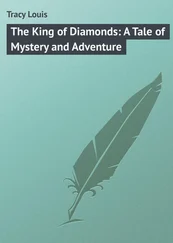

‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’ Quaid demanded, taking hold of Brive’s arm with one hand and removing the papers that the doctor was holding with the other.

‘What do you think? I’m clearing up the mess,’ said Brive, pulling away.

‘No, you’re bloody well not. You’re interfering with the evidence. That’s what you’re doing. And if you carry on, I’ll put you in handcuffs. Do you hear me?’

Brive didn’t answer but instead turned away with a surly expression on his face, nursing his arm as his wife came past him into the room. Quaid kept his eyes on Brive, noting how he kept shifting from one foot to the other, unable to keep still, and how he couldn’t stop nervously rubbing his hands together all the time, as if he were unconsciously trying to wash away the evidence of some recent transgression, while his eyes kept darting back towards the documents on the floor as if he were considering another move in their direction.

Quaid prided himself on being able to tell if a man was lying or hiding something from him, and this medicine man with the funny foreign-sounding name was doing both. Quaid was sure of it. From the moment he’d clapped eyes on him, the inspector had taken an instant dislike to the victim’s son-in-law. He distrusted the fussy triple knot in Brive’s navy-blue bow tie, and it worried him that half of what the doctor said just didn’t add up. Brive said he’d come over because he was concerned about his wife’s safety during the air raid, but then he’d shown no interest in going to her side when he’d discovered that she’d been a witness to her father’s murder. Instead his priority had been to get up the stairs and start interfering with the evidence. And then there was the way that Brive had shown up at the crime scene minutes after the police, even though by his own admission no one had telephoned him or asked for his assistance. He said he was looking for his wife, but why had he been so certain that she was going to be at her father’s?

It was a damned shame that the dead man’s daughter hadn’t got a look at the man who’d pushed her father – too dark, apparently, like everything else in the damned blackout.

‘You say your father was saying “no”. Is that all? Did you hear anything else?’ Quaid asked, turning to the dead man’s daughter. Ava, she was called – a pretty woman with a pretty name. God knows how she’d ended up married to this creepy doctor, Quaid thought, shaking his head.

‘He said: “No; no, I won’t. No, I tell you.” I could tell he was frightened – he kept saying “No”. And there was someone else saying something, but his voice was soft. I couldn’t hear any of the words.’

‘His – so it was a man?’

‘I don’t know. I assume so,’ she said, turning away. He could see that she’d started crying again. Perhaps he shouldn’t have started out with asking her about the murder, but where the hell else was he supposed to start?

‘Okay,’ he said, frowning. ‘I understand. Let me ask you this: Do you normally come over here when there’s a raid?’

‘Sometimes,’ she said in a barely audible voice. ‘It depends.’

‘On what?’

She opened her mouth to speak, but the words didn’t come. Instead she bit her lip and looked away, out of the window towards the wandering beam of a lone searchlight still operating out of the park opposite, despite the sounding of the all clear. The woman was in a bad way. That much was obvious. Quaid felt sorry for her. Her husband, standing morosely over by the door with a sullen look on his face, wasn’t giving her any support at all. The only person who was trying to help was the old lady from downstairs, who’d followed them up the stairs with a cup of tea, which now sat untouched on the low table beside Ava’s chair.

The kind thing would have been to allow the poor woman to go home and sleep, but Quaid resisted the temptation to let her go. He needed to get her version of events while it was still fresh in her mind.

‘Look, have some of this tea,’ he said in a kindly, fatherly voice, picking up the cup and wrapping the woman’s shaking hand around the handle. ‘It’ll make you feel better.’

‘We don’t drink tea. We never have,’ said Bertram, talking over Quaid’s shoulder.

Quaid couldn’t believe what he was hearing; he almost dropped the cup. Everyone drank tea. It’s what British people did to get them through the horrors – make it, distribute it, drink it. It was downright unpatriotic not to like it.

But Bertram’s intervention seemed to revitalize his wife in a way that nothing else could. She glanced over at him and then, as if making a conscious decision, began to drink the tea. Quaid made a mental note – there was no way these two lovebirds were happily married.

‘I come in the mornings to make my dad his lunch, and then, when I go, I leave him his supper – on a tray,’ said Ava, putting down the cup with a shaking hand. She spoke slowly, and there was a faint lilting cadence in her voice that Quaid couldn’t place at first, but then he realized that it was the remnants of an Irish accent. Which was where she must have got her bright green eyes from as well, he thought to himself. ‘And to begin with, I didn’t come back when the raids started because I thought he’d be sensible and go down in the basement with the neighbours. But then Mrs Graves – the woman you met, she was here a minute ago – she told me he was staying up here, refusing to come down. Like he’d got a death wish or something …’

‘There’s no need to exaggerate, my dear,’ Bertram said primly.

‘Please let the lady answer the questions,’ said Quaid, shooting him a venomous look.

‘He’s obstinate and pig-headed, always thinks he knows best,’ Ava went on. It was as if she were unaware of the interruption, and Quaid noticed her continued use of the present tense in relation to her father, as if some part of her were still in denial that he was dead. ‘I asked him to come and stay with us, but he wouldn’t hear of it. Oh no, he’s got to be here with his stupid books.’

Ava’s resentment was obvious as she gazed up at the overflowing shelves on all sides. It couldn’t have been easy being her father’s daughter, Quaid thought. Not that being married to Dr Bertram Brive looked much fun, either, for that matter.

‘So you started to come over here to see if he was all right?’ asked the inspector, prompting her to continue.

‘Yes.’

‘When?’

‘A few days ago.’

‘And did he go down to the shelter?’

‘Yes. But I knew that he wouldn’t have done without me being here.’

‘And your husband – has he been over here before in the evenings, like tonight?’

‘No.’

‘Even when there have been air raids?’

Ava shook her head.

‘I fail to see the relevance,’ said Bertram, whose face had turned an even brighter shade of red than before, although whether from anger or anxiety it was difficult to say. He was going to say more, but a cry from his wife silenced him.

‘All he had to do was go downstairs—’ She broke off again, covering her face with her hands as if in a vain effort to recall her words – ‘go downstairs’ – because instead her father had taken a quicker way down, falling through the air like one of Hitler’s bombs, landing with that unforgettable crunching thud at her feet. She shut her eyes, trying to block out the vision of his tangled broken body. But it did no good – it was imprinted on her mind’s eye forever by the shock.

‘I should never have let him go out without me,’ she said.

‘Out?’ repeated Quaid, surprised. It was the first he’d heard about the dead man having gone anywhere that day.

‘Yes, he insisted. It was after we came back from the park. I take him there after lunch most days. He likes to go and look at the ack-ack guns, “inspect the damage” he calls it, and poke his walking stick in people’s vegetable patches. They’ve got the whole west side divided up into allotments now,’ she added irrelevantly. ‘Digging for victory. I remember him making a joke about that, turning over some measly potato with his foot. Laughing in that way he has with his lip curling up, and now, now—’ She broke off again, looking absently over towards the fireplace, where a walnut-cased clock ticked away on the oak mantelpiece, impervious to the death of its owner two floors below.

Читать дальше