1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...17 In the oriental tradition passed down from the city’s Byzantine past, respectable women were supposed to be kept at home or closely chaperoned on permissible outings. Some of the sequestered women must have led very boring lives. The two sulky ladies on a terrace in Carpaccio’s famous painting, which is now thought to portray a bride and her companion, might have looked less miserable had they been the courtesans they were once thought to be. In the upper panel their men are enjoying a day out duck hunting in the lagoon. Even the shopping for groceries was done by the men of the household, who could be seen strolling or riding on horseback through the markets, judging value for money with the trained eyes of professional merchants, while their housebound women supervised the cleaning or did it themselves; although there were fewer domestic servants than one might expect in a wealthy city, foreigners commented on the sparkling cleanliness of Venetian houses. When they did go out, perhaps to church or to attend a wedding or to shop for clothes and accessories in the boutiques on and off the Merceria, they teetered along on their zoccoli, the ridiculously high-platformed clogs that restricted their pace and emphasized their vulnerability, making them look like dwarfs on stilts and requiring the support of servant chaperones: the longer the train of servants the higher the status of the woman.26

Venetian women’s addiction to the latest bizarre fashions may in some cases have been a compensation for otherwise dull lives, but it would be anachronistic to infer that the displays of breasts and jewels were primarily intended to brand women as their husband’s sexual property. Their dowries, the larger part of which was returned to them as pensions on the death of their husbands, meant that wives and widows enjoyed a high degree of economic independence. It says something about their literacy and the respect accorded them by their husbands that women were increasingly designated as executors of their husbands’ estates; and since their husbands were usually at least twenty years older, there were a good many rich Venetian widows. Some women discovered along with their freedom a talent for investing in property and made money on their own account. Venetian women of all classes, although certainly not ‘liberated’ in our sense of that condition, were more active in business than women in other cities. Despite a dictate issued by the Council of Ten in 1506 imposing penalties on husbands who permitted their wives to dine out and attend theatrical entertainments alone, there were at least some independent-minded wives who defied the sanctions against appearing unchaperoned in public. Foreigners were surprised to see women dining out alone. And as early as 1487 a German guest at the monastery of Santi Giovanni e Paolo was astonished to observe elegantly dressed young women moving openly in and out of the dormitories and cells of the monks.

The Milanese priest who had described the shopping opportunities, and who evidently had a practical mind, wondered how the women kept their dresses from falling off their shoulders. But if the older generation of Venetian patricians disapproved of the bizarre fashion for veiled faces and bosom-revealing bodices worn by women whose bodies, perfumed with amber, musk and civet, could be scented from a distance, sumptuary legislation failed to make much difference to their showy dress sense, and there was no law against décolletage until 1562. Sanudo was impressed by the size and value of women’s jewellery:

The women are truly very beautiful; they go about with great pomp, adorned with big jewels and finery. And … adorned with jewels of enormous value and cost, necklaces worth from 300 up to 1000 ducats, and rings on their fingers set with large rubies, diamonds, sapphires, emeralds and other jewels of great value. There are very few patrician women (and none, shall I say, so wretched and poor) who do not have 500 ducats worth of rings on their fingers, not counting the enormous pearls, which have to be seen to be believed.27

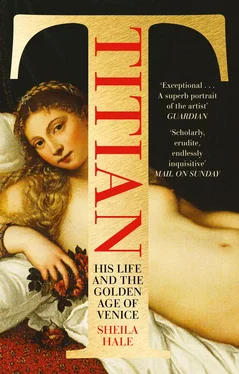

The erotically charged atmosphere in early sixteenth-century Venice is almost palpable in the paintings by Giorgione, Giovanni Cariani, Palma Vecchio, Titian and others of women whom we can no longer identify but whose inviting eyes and bared breasts leave no room for doubt about their availability. Titian was not the first artist to paint naked women, but he was the first to use live models, and to paint them lying down. Lightly draped or naked, Titian’s anonymous women, as real to us today as when his contemporaries thought they saw the blood pulsing beneath their trembling flesh, display an overt sexuality that had never been seen before in painting.

On his map of Venice Jacopo de’ Barbari enlarged the scale of the arsenal to emphasize its importance. But there are fewer warships than would have been present at a time when Venice was at war with the Ottoman Turks. At the top of the map Mercury, god of communications and commerce, emerges from a cloud. Neptune, god of the sea, rides on his sea monster among trading galleys that are coming and going, riding at anchor, preparing to unload passengers and goods on to lighters. But a third tutelary deity of Venice, Mars, god of the wars fought in order to expand and maintain its trading empire, is absent. De’ Barbari’s black and white dolls’ city is at peace with itself and the world, serene, silent and inhabited only by a few stick people to indicate the scale of the buildings.

The true situation was very different. The mid-millennium, when soothsayers all over Europe were predicting the end of the world, was actually a troubled time for the Most Serene Republic. In 1498 reports had reached the Rialto of Vasco da Gama’s exploratory voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, and three years later the worst fears were confirmed by news that twelve Portuguese ships had been spotted in Aden and Calicut. The threat to the Venetian monopoly of the spice trade, which had already been disturbed for several years by the disruption of overland routes during wars in northern Italy and Turkish wars in Persia, had been followed in 1499 by a series of bank failures, which ruined some of the wealthiest patrician owners of the trading galleys.

It was in that same annus horribilis that one of the largest war fleets ever prepared in the Venetian arsenal suffered a catastrophic defeat by the Turks. Two Venetian gunships were blown up and the Turkish cavalry invaded the Friuli as far as the River Isonzo (where Titian’s grandfather Conte took part in the defence). ‘Tell your government that they have done with wedding the sea,’ the Turkish vizir gloated to the Venetian ambassador in February 1500, adding that it was the sultan’s turn now to be the bridegroom in the annual symbolic ceremony of the doge’s marriage to the sea. The Turk – ‘signor tremendo’ as Marin Sanudo dubbed the increasingly militant Ottoman Empire – had been harassing Venetian trading convoys since the Turkish conquest of Constantinople half a century earlier. It had been mostly a cold war, but now flared up into four years of fighting, during which the Venetians lost more essential naval bases in Greece and Albania, and it led to a temporary halt of Venetian trading in the Levant.

The setback to overseas trade was not the mortal blow that some historians have made out. Revenues from the terraferma – ‘the most delightful, populous, and fertile part of Europe … the flower of the world’, as it was described by a Vicentine nobleman in 150928 – were about twice those from the sea empire. Nevertheless, taxation and customs duties on the oriental spices that passed through the mainland accounted for a large proportion of the state income, and the interruptions to overseas trade were at the time cause for deep concern. The reaction was swift and dramatic. All but the most profitable of the shipping lanes – those that went to and from Beirut and Alexandria – were abandoned. The ruling class relinquished its long-cherished exclusive right to own and profit from the trading galleys, and more of the merchant noblemen who had formerly spent much of their lives at sea stayed at home and spread their risks by investing in manufacturing, and in agriculture, property, mining and other industrial enterprises on the mainland. Venetians made new fortunes from expanded industries: the weaving and dyeing of silk and wool, the manufacture of fine soaps, leather working and sugar refining, all profitable commodities in the home and export markets. The fine-spun Venetian glass produced by forty or so furnaces on Murano was increasingly exported to the rest of Italy and the Levant and as far as Portugal, Spain and the Indies. Nevertheless, the diarist Girolamo Priuli was pessimistic about the shift from overseas trade to agriculture and industrial production: ‘In losing their shipping and their overseas Empire, the Venetians will also lose their reputation and renown and gradually, but within a very few years, will be consumed altogether.’29

Читать дальше