Praise

Dedication

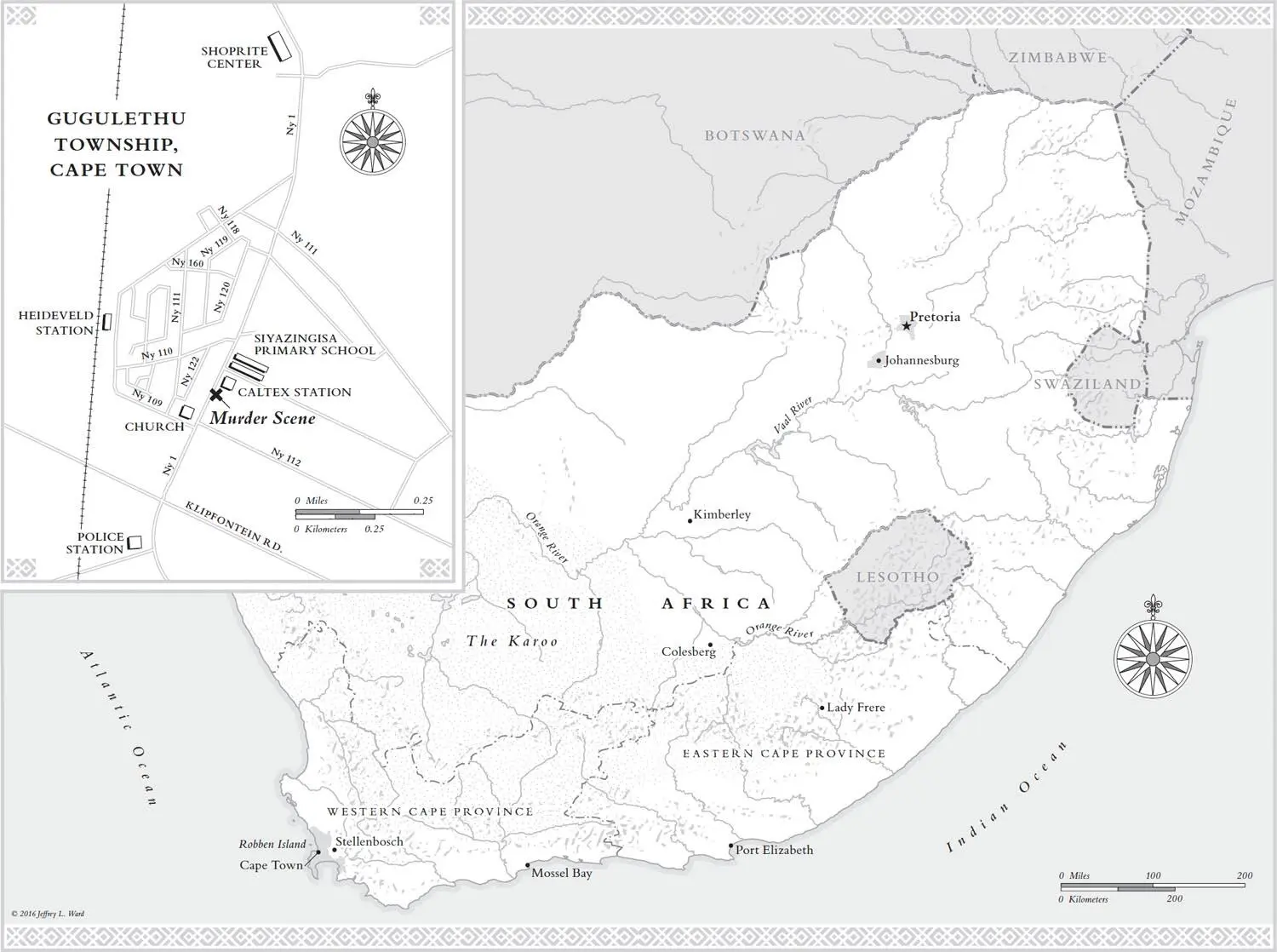

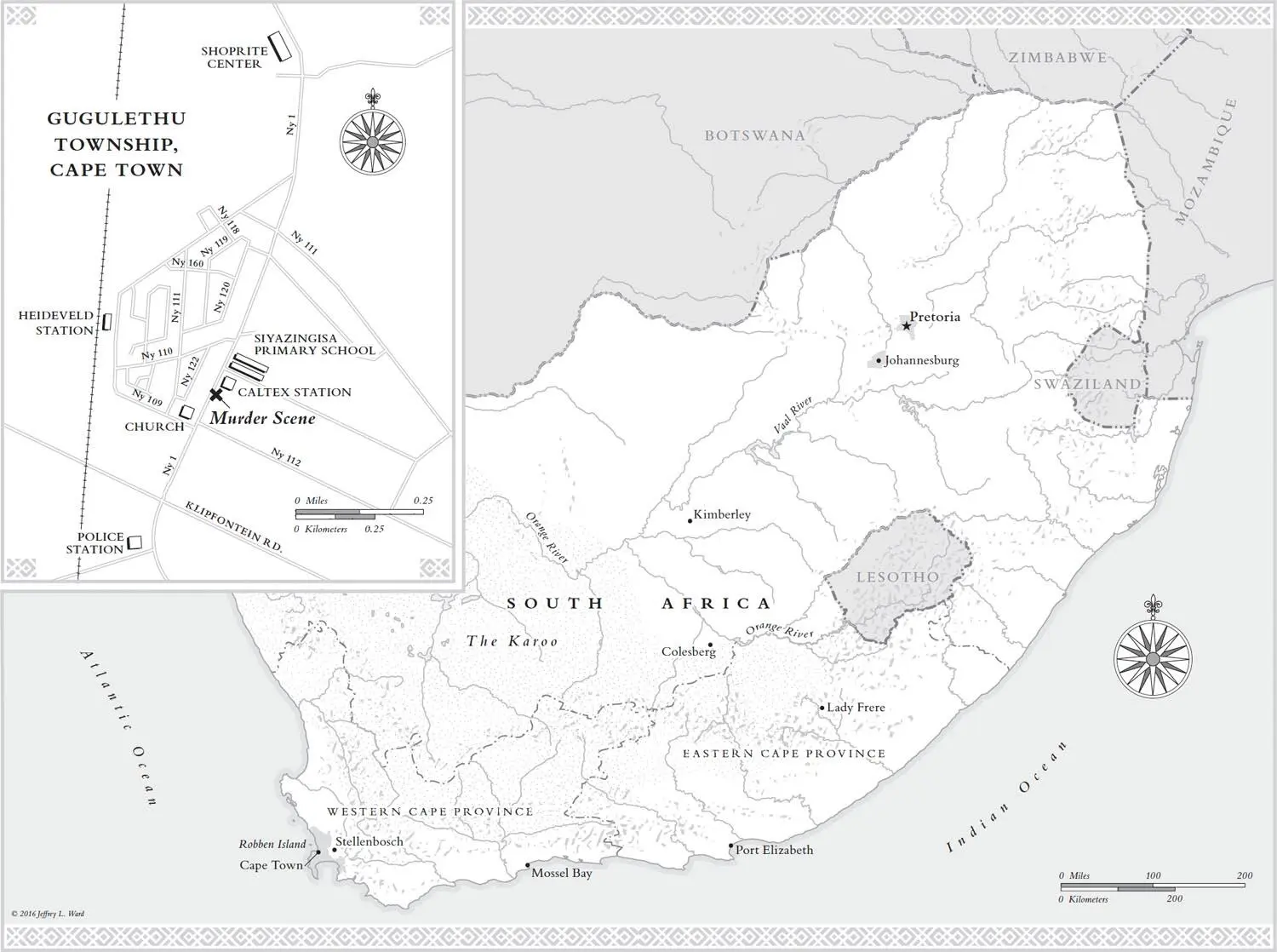

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Acknowledgments

Permissions Credits

About the Author

About the Publisher

Some stories are true that never happened.

—ELIE WIESEL

The journalists and documentarians and small-time film producers filed out of the van and toward St. Columba Anglican Church, a gray-brick building on the corner of NY1 and NY109 in Gugulethu, a township eleven miles outside Cape Town city center. Easy and I stayed behind, he in the driver’s seat and me on the passenger’s side. Easy was a short, compact man with butterscotch skin and a large, round, clean-shaven head. At forty-two, he had this weird ability to shape-shift. Did he look like a hardened old gangster? Yes, some days. Did he look like an adorable, harmless child? Yes, some days. In one of the photos I’ve snapped of him over the years, he is menacing, crouching on the ground with a cigarette between his thumb and forefinger, his band of brothers behind him, one of them holding up a disembodied sheep’s head. But in the next, he’s curled on a small stool, cradling his infant son and smiling as his ten-year-old daughter drapes herself over his shoulder.

Easy laughed generously, from the belly, and moved in quick spurts. His features were framed by a constellation of small dark scars: from a knife fight, a stick fight, an adolescent bout with acne, that time he crashed a van into a horse in the middle of the night and then fled, that time the taxi he was riding in collided with a hatchback, and a recent incident involving a scorned ex-girlfriend with long nails and a vendetta. His arms were dotted with fading ballpoint-pen tattoos—one pledging devotion to a long-defunct street gang, one to a prominent prison gang, and one to an old flame named Pinky. The first one had become infected immediately, when he was fifteen, and his mom had spent months tending to it. After that, for a few years at least, Easy felt like it made him look particularly tough.

I liked Easy very much. I won’t pretend otherwise. But then again: precisely twenty years before our meeting in the van, on August 25, 1993, and approximately fifteen yards away, Easy had been part of a mob that had hunted down a young white American woman. If you plucked her out of that moment in history and slotted me in, my fate would have likely been the same. Easy chased her through the streets, chanting the slogan “One settler, one bullet,” and hurled jagged bricks at her. He stabbed at her as she begged for her life. She died, bleeding from her head and her chest, on the pavement just across the road.

At least this is the crime Easy repeatedly claimed to have committed. He was convicted of her murder, and sentenced to eighteen years in jail. He’d done it, he publicly stated, because “during that time my spirit just says I must kill the white.” The dead woman was named Amy Biehl, and she was twenty-six years old.

Once we finished our conversation, Easy and I hopped out of the van. He locked the door and patted the hood. The vehicle was a shiny silver donation from a local auto dealership that said across the side in bold letters: THE AMY BIEHL FOUNDATION.

We walked toward the church together, but as I stepped toward the door, Easy lingered in the winter sunshine. “I’m coming now,” he said. This was South Africanese for “I’ll be right back.”

I went on without him. A sorry-eyed man in an ill-fitting suit motioned me into a pew. I slid in and scanned the room, its high ceilings, its tall burning votives. On a portrait nailed high above on the wall, a white Jesus, as lithe and glossy as a Hollywood star, reclined among a small herd of angelic lambs. Behind the pulpit hung an enormous cross.

I could see Amy Biehl’s mother, Linda, sitting several rows ahead, her sharp platinum bob distinct in a dark sea of cornrows, weaves, wraps, curls, and towering church hats. Linda was the sort of woman who swept into town, and then swept into rooms, and then swept around rooms, her lipstick and eyeliner painted in broad, unbroken lines. She was nearly seventy. She liked to tell stories to rapt audiences. She always set her jaw and held her head high, and when I had first met her, just over a year earlier, I had found her to be impossibly composed. But with time, I came to notice that her body betrayed her attempts at imperturbable dignity: her shoulders slumped forward and she seemed, often, to be fighting against a great weight that threatened to drag her down.

Her friends, a pair of white American filmmakers, flanked her in the pew. She held in her arms a three-year-old black girl, hair cropped close to the head, dressed all in purple. The father of the girl was a man named Ntobeko Peni. According to all available reports, court records, and his own voluntary confession, Ntobeko had joined Easy and two other men in the attack on Amy. Back then, Ntobeko was a teenager and Easy and the other men were in their early twenties.

South Africa was in the final, fiery days of apartheid, when the entire country seemed poised for civil war. The young men, in the stories they would later repeat to various officials and commissions and journalists, had just left a political rally for a fringe militant party called the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, or the PAC. Ntobeko and Easy were among around one hundred young people marching down NY1, the street where the church still sits. After forty-five years of state-sanctioned racial segregation, which saw black South Africans stripped of basic human rights and contained in slums, Nelson Mandela was poised to be the first black president of the country. Apartheid was on its way to being dismantled.

Amy, a Fulbright scholar at a Cape Town university, had spent nearly a year researching the rights and roles of disadvantaged women and children of color in this transitioning new democracy. That day, she had agreed to give two black students a lift home to the townships. As she drove by, the marchers spotted her, her long dirty-blond hair a bull’s-eye. The crowd, knowing nothing about her, decided she looked very much like the oppressor. Her death, they claimed to believe, would further their cause to bring African land back to indigenous Africans: One settler, one bullet. Or maybe they were just looking for revenge on a pretty afternoon. They pulled Amy from her car, chased her down the road, and stoned and stabbed her to death on a little patch of grass in front of a gas station.

Four men—Easy and Ntobeko among them—were tried and convicted of Amy’s murder and were sentenced to eighteen years in prison. But in 1997, they applied for amnesty at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, South Africa’s experiment in restorative justice. Chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the commission offered release and a clean slate to those who, upon taking responsibility, fully and honestly, for their apartheid-era crimes, could prove that their misdeeds were politically motivated.

In 1993, Linda, a stay-at-home mom turned clothing saleswoman, and her husband, Peter, a businessman, lived in a wealthy California coastal suburb. They had never before set foot on the African continent, but soon after Amy’s death they flew to Cape Town. They immersed themselves in the rapidly changing country. They educated themselves on its complex political situation. They threw themselves into social welfare programs and spent time with the political elite of the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela’s party and the party Amy had admired.

Читать дальше