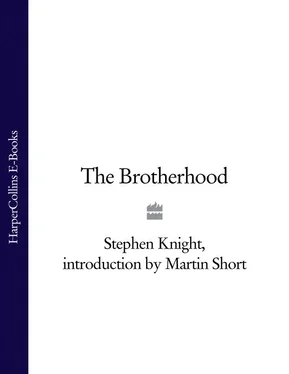

When news of his conversion reached Freemasons’ Hall, the London HQ of the United Grand Lodge of England, the brotherhood used it to try and discredit him. In due course it called him ‘a devotee of the Sri Rajneesh Bagwan cult’ [sic]. Maybe this would convince some people to reject his view of Freemasonry but it struck me as laughable that members of one cult should demean someone else for belonging to another. Not just the pot calling the kettle black, but the men in blue aprons calling the orange people potty.

In fact Stephen followed the Bhagwan for only two years. By the time he died he had been received back into the Church of England. Maybe his death had been hastened by his decision to stop an 18-month course of chemotherapy. This had been prescribed to kill the 30 per cent of the new tumour which surgery could not remove because it was too close to the parts of the brain that control speech and movement. Certainly he knew he was going to die fairly soon so he switched to the natural therapy of a diet of fruit and vegetables to avoid the nausea and vomiting brought on by chemotherapy.

When he died in July 1985 Stephen was just 33 years old. For friends and foes of Freemasonry this fact had serious implications. It convinced some folk that he had indeed been sentenced to death by Masonic justice. To Freemasons the number 33 signifies the 33 degrees of the Rose Croix, an elect ‘Christian’ Masonic order which Stephen had attacked in The Brotherhood . Thirty-three was also Christ’s age when he ‘died’, a death which Rose Croix Masons re-enact in their 31st degree ritual.

To me such hocus-pocus meant nothing. I was just saddened by his death.

More than 20 years after The Brotherhood was first published, new readers may ask several questions. What is the book’s legacy? Has it had a lasting impact on public perceptions of Freemasonry? Has it affected Freemasonry itself?

The importance of The Brotherhood lies not so much in its revelations but in the fact that it brought Freemasonry back into public debate after a century when it had scarcely been discussed. This was not the fault of Freemasons alone. It lay as much with self-censorship by writers, editors and (latterly) radio and TV producers, who, if not Freemasons themselves, may have been scared stiff of retribution from Freemasons above and around them. For generations the brotherhood was spoken of rarely in public, and even then in whispers by bitter men who felt the brotherhood had ruined or victimized them, or by lonely wives wondering if that little case their husbands left home with once a month really did mean he was going to a lodge meeting or if it was just cover for a night out with another woman. The rest was silence.

The Brotherhood shattered that silence but Stephen wasn’t the only person throwing stones at Masonic temples at the time. At last a few newspapers and TV programmes were mocking the institution or raising allegations of corruption. When the book turned into a surprise bestseller, Stephen was invited on phone-in talk shows and defended his book against all-comers. He did well despite his faltering speech brought on by his illness and treatment.

I spent much of the years 1982 to 1984 in the USA, researching and producing a vast TV documentary series on an equally fascinating secret society, the Mafia or La Cosa Nostra, with which Freemasonry shares many characteristics. When Stephen died, I felt privileged to be asked to write a sequel to The Brotherhood . I based my book partly on a stack of 500 letters which had been sent to Stephen’s publisher and his steadfast agent, Andrew Hewson. Many came from disillusioned Freemasons, willing to act as informants or ‘whistle-blowers’ (as we now call purveyors of inside information). I called my book Inside the Brotherhood because it was based partly on what these renegade brothers were telling me. I also read a vast amount of Masonic literature which revealed many of the ludicrous, lunatic claims that the brotherhood has made for itself over the past 300 years. I added a lot of hard evidence from recent court cases that confirmed Masonic corruption in public life - notably among police detectives and especially in Scotland Yard’s elite units such as the Flying Squad and the Obscene Publications Squad.

Naturally I recommend readers of The Brotherhood to read the sequel which also became a best-seller, spending many weeks in the Sunday Times non-fiction charts. It even reached number one in Ireland where the Catholic majority opposes Freemasonry but where Masonic lodges survive, remnants of the old Protestant ascendancy. The book stirred up further controversy. In 1989 it was the basis for a documentary series which I produced and narrated. This went out at peak-time on ITV, then Britain’s most watched station.

By now there was hardly anyone in the country who did not know something about Freemasonry and its secret rituals, which we had enacted with the help of renegades. We also exposed the crimes and rackets of other Freemasons. The order perpetually claims it is the victim of conspiracy theories but refuses to admit that its own oaths of ‘mutual defence and support’ and its cell-like structure are ideal for concocting, perpetrating and covering up conspiratorial acts.

In the early 1990s the brotherhood struck back, in print at least. Suddenly books appeared, written by Freemasons who were breaking their sworn oath not to reveal the order’s secrets but seemed to have the go-ahead to do so. Their books were supportive of Freemasonry and extolled the less reprehensible side of its history.

In the meantime the United Grand Lodge of England, along with its parallel grand lodges in Scotland and Ireland, tried to give an impression of greater transparency, opening their temples to the public and stressing their generosity to non-Masonic charities, but at no point have they disclosed or performed their rituals to the public: no show of ropes or cabletows around necks, no daggers or poignards to the heart, no blindfolds or hoodwinks, no rolled-up trouser legs and no resurrection routines. So no real openness.

Despite these gestures, concern was growing that Freemasonry still had the covert malign influence exposed in our Brotherhood books and elsewhere. Many local authorities were now obliging elected councillors and full-time employees to fill in forms stating if they were Freemasons. Cries of discrimination were over-ruled or neutralized by requiring that the form-fillers declare membership of any other secret or would-be secret societies.

In 1996, for the first time in its history, Freemasonry was scrutinised by the highest authority in Britain: Parliament. The prime mover was Chris Mullin MP, the former investigative journalist renowned for his work on the miscarriage of justice done to the Birmingham Six (six men wrongly imprisoned for 16 years for the 1974 IRA bombing of two Birmingham pubs that killed 21 people).

Taking on this task was the Home Affairs Committee of the House of Commons, of which Chris was then deputy chairman. A cross-party outfit, its chairman was the Conservative MP, Sir Ivan Lawrence. They agreed that the time had come to put the brotherhood under the microscope, and decided to focus on ‘Freemasonry in the Police and the Judiciary’. It fell to me to be the opening witness.

On Wednesday 18 December 1996 I was questioned for two hours by eleven Committee members. Ten were men. Eight said they were not Freemasons. One was a Freemason but said he had not attended any lodge for over 20 years.

The Committee’s official report shows that I answered 144 questions. It was a demanding experience though not unpleasant, the examination benign but rigorous and robust. I had only a few sharp words with one member - not the Freemason. Overall I felt the Committee was making a genuine effort to gather information, as impartially as possible, about the brotherhood’s influence not just in the police and judiciary but in British society as a whole.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)