This book is an account of how the determination of longitude at sea became feasible, and of how global positions could be agreed and the world known with greater clarity. On the one hand, it is a tale of seafaring, time and astronomy; on the other, it concerns commerce, competition and conflict, exploration and empire. The ‘longitude problem’, as it has become known, was a technical challenge that taxed the minds of many of the great thinkers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. Galileo Galilei, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton all grappled with it as a puzzle that seemed insoluble. Finding the longitude became a ridiculous quest only to be undertaken by the deluded, until the simultaneous development in the late eighteenth century of two practicable, complementary means of fixing a ship’s position changed everything. These methods gradually came into use, both for routine navigation and for creating better charts of the world’s oceans and coastlines, mapping the Earth in ways that had been inconceivable in 1494.

The quest for longitude is an international story, and this account touches on important work in the Netherlands, France and other countries from the late fifteenth century onwards. However, the main focus is on events in Britain from the early eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth. It was in Britain that the rewards offered under the Longitude Act of 1714, and the creation of an administrative structure to support promising ideas, led to the testing and development of the two methods that would eventually come into standard use at sea.

Why it should have been in Britain that the problem was solved is one of the issues this book addresses. The answer has much to do with the relationships operating between government, commerce and science at the time. Longitude solutions were encouraged by the British state through the 1714 Act, as had happened elsewhere; but, crucially, the new incentives addressed a British audience of skilled, commercially driven artisans working in a context of public discussion of new ideas. The Act therefore played to the strengths of Britain’s metropolitan culture of craft skill and open intellectual debate.

Longitude mattered greatly at sea, but much of the story of how it was found and then deployed took place in cities on land, among academics and artisans. Crucially, the Commissioners of Longitude named in the 1714 Act eventually took on the role of encouraging promising work over many years, and of fostering the means by which the new techniques could be used on all ships, not just Britain’s alone. It was not simply a matter of paying a reward; good ideas needed to be turned into reliable tools. Once they had been, Britain’s existing maritime dominance allowed its navy to lead efforts to deploy the new methods for finding longitude in order to chart the world with certainty. As a result, a new line, now passing through the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, would come to divide the globe and define every ship’s longitude.

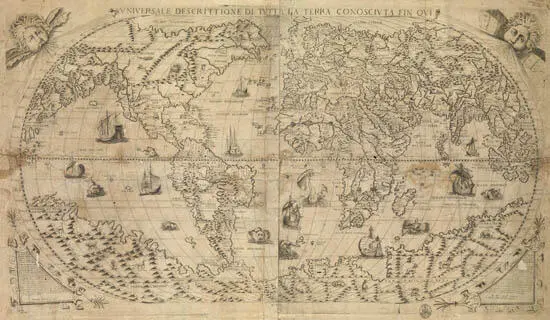

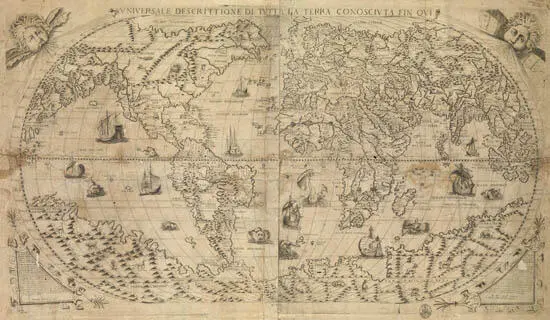

A map of the world, by Paolo Forlani, published by Fernando Bertelli, 1565

{National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London}

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.