In practice, every plantation was a petty kingdom where violence and terror was the norm and compassion as rare as window-glass. To whom did the governor report the abuses of the plantation system and with what consequence? For generations of ministries, Colonies had been bundled up with War – the one a consequence of the other. The loss of the American colonies made the humanitarian argument for an end to slavery very difficult for Britain to endorse. As the home country was forced to admit, in tolerating its calamities in the Caribbean it was also hanging on grimly to – and in the wars against the French doing all it could to increase – what was left of what it once had.

Soldiers and sea-captains had given Britain the original imperial advantage. So assiduous was Captain Cook in exploring the South Seas, for example, that the Whig wit Sydney Smith once estimated ruefully that if there was a rock anywhere in the world large enough for a cormorant to perch on, someone would think to make it British. It was a witty exaggeration of a not uncommon point of view, for the chief concern of home government was not the glory of overseas possessions, or the honour of their discovery, but how much it cost to garrison them. A common statistic of the early nineteenth century was that simply having a seaborne empire employed 250,000 men and tied up 250,000 tons of shipping. For many years the expenditure Britain was put to in its geopolitical adventures far exceeded revenue.

In this picture, Jamaica was strikingly different, a piratical treasure chest with the lid thrown back. Figures provided to the House of Commons in 1815 showed a value in exports of £11,169,661. Such public works as existed were maintained by a nugatory tax income of £1200. This was the plantation system at its apogee.

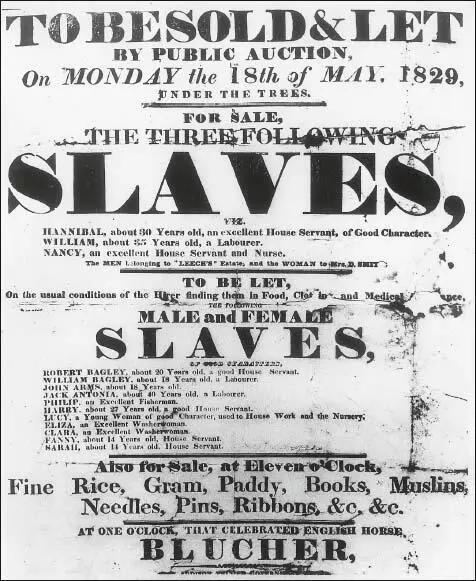

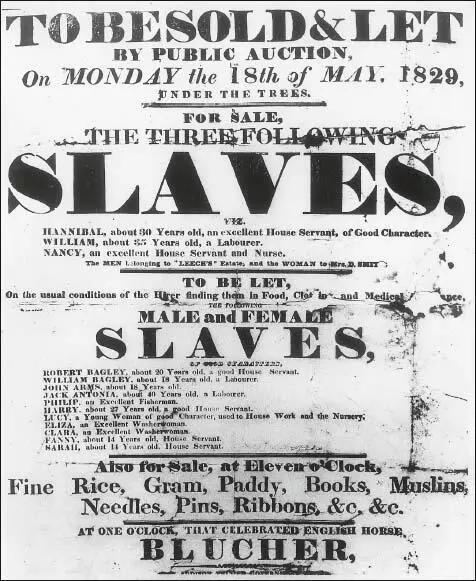

Everything that was so spectacular and fantastical about Jamaica’s wealth derived from the island’s dependence upon slavery. The standard agricultural implement was not the spade or the hoe but the cutlass. The standard punishment for an absconding slave was to lop off both ears. Nobody thought it of any great account. Visitors to Jamaica, who knew very well that fortunes were being made and fine country houses raised by the sugar merchants at home in England, were amazed by the coarseness and vulgarity of the planter society put in place to garner the profits of these great men. Most striking of all, the English men and women who lived on Jamaica and ran it for their absentee landlords affected to need nearly a third of a million slaves to sustain their position. Wellington had commanded an allied force of half that number to make himself master of all Europe.

This is how the story begins, on an island remote from Europe by 3000 miles. The word old-fashioned sits well with the Jamaican colonists. At the end of the war with Napoleon Britain controlled almost every Caribbean island – and who had won these great victories if not table-thumping, punch-drinking patriots cut from the old cloth, men William Hickey would be honoured to call his friends? Jamaica in 1815 was in triumphalist mood. It did not need capital – its wealth was in its labour force. It did not need fine gentlemen and, as it was making clear in its own surly and combative way, it did not need evangelical ministrations either. Put simply, Jamaica did not need improvement.

This shortsightedness was to be its undoing. Fifteen years later the value of sugar fell from £70 a ton to £25. In 1833, a law enacting the complete emancipation of the slaves changed the nature of the trade irrevocably. The unimaginable came to pass. The old planter society, which seemed as permanent and reliable as sunrise, was soon enough nothing but a romantic ruin. The factor in play here was much more important than the price of sugar. The reforming zealotry of a new age turned its mind to overseas possessions and found them wanting. The haphazard collection of islands and factories, plantations and anchorages was, within a generation, transformed. The Empire, which before had hardly merited its capital letter, became a single thing, an idea: in the hearts and minds of this new age, a crusade.

The people whose lives make up this book were not law-makers; neither were they in any sense radicals. They were Victorians of a particular stamp – adventurous, at times maddeningly complacent and, as far as feelings for their country were concerned, sentimental to a fault. None of them went to university – two of them were soldiers – and it could be argued that what we see in their experience is merely the exchange of one form of naivety for another. Certainly their patriotism was unquestioning enough to jar a modern sensibility. ‘Hurrah for old England!’ one of them cried as the scarecrow figures of Speke and Grant tottered into Gondokoro on the Nile, after walking from one hemisphere to the other. This is a shout whose echo has died completely, except perhaps on foreign football terraces, where the Union flag is more likely to be worn as a pair of shorts than a banner snatched up in the heat of battle.

What distinguishes these men is something new to the history of the nation. To their undoubted bravery was added the utter conviction of being chosen for a purpose even a child could understand. Throughout the nineteenth century there existed the belief that a Briton was the summit of God’s creation and the instrument of His will. This was never so clearly demonstrated as when he was abroad. Once a more or less random collection of properties – in which, for example, it could be contemplated that to exchange the whole of Canada for the strategic anchorage of St Lucia was a sensible trade with France – the Empire became the expression of a divine purpose. Nor was dominion over other people simply for economic advantage.

Let us endeavour to strike our roots into their soil, by the gradual introduction and establishment of our own principles and opinions; of our laws, institutions and manners; above all, as the source of every other improvement, of our religion and consequently of our morals.

This is Wilberforce, writing about India. The great evangelical Christian is indicating how not just India but the whole world was to be set free – by imposing upon it, however sympathetically expressed, a superior way of being. If in the end breechloading rifles and gunboats were the swifter teachers of this great lesson, it had deeper and, to such as Wilberforce, nobler origins. It started with the determination that nothing should be left undone to help the peoples of the world understand that their own histories, their own cultures and religious beliefs were mere shadows. The men whose story this is were evangelicals like Wilberforce only in this one sense: they took the missionary zealotry implicit in evangelism and expressed it in what seemed to their age heroic action. They were that new thing that animated Britain for a hundred years: they were imperialist romantics. Their virtue was in their character.

A young man called Samuel Baker visited Jamaica in the year of the great hurricane to inspect his family estates. They had come down to him through his father, the redoubtable Captain Valentine Baker. Thirty years earlier, while commanding a mere sloop, Captain Baker had engaged a French frigate, forced it to strike its colours and then brought it into Portsmouth in triumph. (The unfortunate French captain, when he realised how small a vessel had overwhelmed him, went below to his cabin and cut his throat.) A French-built frigate was considered the acme of naval architecture and when the news was carried across country to Bristol, the merchants there made haste to present Baker with a handsome silver vase as a mark of their appreciation. The gesture was not entirely patriotic. At the time of this stirring engagement Captain Baker was sailing under letter of marque. A less polite way of describing his activities was to call him a privateer. Baker rose in the estimation of his employers and 1804 found him master of the Fame , as large an armed vessel as ever left Bristol under private commission. With his share of the profits he bought land – Jamaica land, tilled by black slaves.

Читать дальше