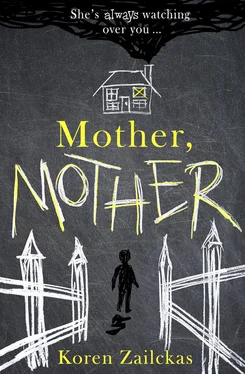

Mother, Mother

Koren Zailckas

A family is a tyranny ruled over by its weakest member.

—GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

through fog, it is impossible to perceive fiery eyes greedy claws jaws through fog one sees only the shimmering of nothingness … were it not for its suffocating weight and the death it sends down one would think it is the hallucination of a sick imagination but it exists for certain it exists

—ZBIGNIEW HERBERT,

“THE MONSTER OF MR. COGITO”

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page Mother, Mother Koren Zailckas

Epigraph A family is a tyranny ruled over by its weakest member. —GEORGE BERNARD SHAW through fog, it is impossible to perceive fiery eyes greedy claws jaws through fog one sees only the shimmering of nothingness … were it not for its suffocating weight and the death it sends down one would think it is the hallucination of a sick imagination but it exists for certain it exists —ZBIGNIEW HERBERT, “THE MONSTER OF MR. COGITO”

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

William Hurst

Violet Hurst

Q & A: Koren Zailckas

Acknowledgments

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

HER FACE WAS the first thing William Hurst saw when he opened his eyes from his not-so-sweet dreams. His mother, Josephine, was smiling down at him, her blue eyes misty-soft, sunlight streaming through her hair, the same way it did to the happy Jesus in Will’s Storybook Bible .

On this particular Saturday, mother was both a noun and a verb.

Behind her, at the end of Will’s bed, was the frog habitat he’d begged for all summer. It had a paddling pond for tadpoles and a rocky ledge where frogs could doze beneath a canopy of green plastic clover.

Will knew he should be jabbering with excitement. There she was, waiting for him to pump his fist and thrash with glee (not that he would ever dare jump on the bed). But something was off. The timing didn’t add up.

“Is today my birthday?” Will asked. “Did I do something to deserve an extra-special reward?”

“No,” Josephine said. “Today isn’t your birthday. And you , little man, are my extra-special reward.”

She reached for the boy’s face, as if to give his bandaged chin a playful pinch or tuck his too-long hair behind his earlobe. But then the phone rang and her freshly moisturized hand froze, suspended in the space. She pulled away and padded off in her slippers to answer it, a Velcro roller tumbling out of her hair and sticking, burr-like, in the carpet.

The house should have been quiet now that Will’s sixteen-year-old sister Violet had been banished. Oddly, the Hurst family home was louder. Even after his mother hung up her cell phone, her voice remained nervous, her actions rackety. Will followed her downstairs to the kitchen, where the radio was already on, cranked to WRHV. Cupboard doors slammed. Silverware barrel-rolled as she jostled the drawers.

The rotten-egg smell of his father’s morning shower wafted down the staircase. The well water was sulfuric. Violet liked to say that hell smells like sulfur. So do places infested with demons. If Will believed his mother—and he had no reason not to—demons were rebels like Violet. They fell from grace when they looked into God’s gentle eyes and announced they didn’t need him anymore.

At the kitchen table, Josephine asked, “Is a noun a doing word, a describing word, or a naming word?”

“A describing word,” Will told her between swallows of oatmeal.

Josephine’s smile—a bright sideways sliver of moon—made it impossible for him to know whether he’d answered right or wrong.

“Let me put it this way,” she said. “Which word is the noun in this sentence: ‘I always know what I am doing.’”

“What.”

“I said, which word is the noun in this sentence—”

“No, Mom. I wasn’t asking, What? I was trying to tell you ‘what’ is the answer .”

“Oh,” Josephine said. “Oh, I was expecting you to say ‘I.’ But I suppose ‘what’ is right in this instance too.”

The portable phone screamed in its cradle. Josephine picked it up and wandered out of the kitchen saying, “No, I told you. I have a twelve-year-old special-needs son. She’s a danger to him. I can’t have her here.”

Will had autistic spectrum disorder with comorbid epilepsy. To him, that always sounded like a good thing—the word spectrum being halfway to spectacular . But Will knew his differences secretly shamed his family, his father, Douglas, in particular. At Cherries Deli, Will was always aware of his dad’s gaze lingering on the youth soccer leagues eating postgame sundaes. Probably, Douglas longed for a sturdier and more social son—a buzz-cut bruiser who could shower and climb stairs unsupervised, without the nagging threat of seizures.

Will’s mother tried to put a positive spin on his health conditions. Once when Will was in a wallowing mood, he’d blubbered, “I’m not like normal people!” And Josephine had consoled him by saying, “No, you’re not. And thank God for that. Normal people are dim-witted and boring.”

Will had received his dual diagnosis nine months ago, and his mother had been homeschooling him ever since. A onetime academic, Josephine was every bit as good as Will’s former teachers. Plus, she custom-made his curriculum. She was patient with Will in math, where it took him ages to grasp square roots, and rode him relentlessly in language arts, where she prided herself on the quality of his writing and his ability to read above grade level.

Violet used to tell Will that he was blessed to have autism. She was studying Buddhism, and she said that Will must have been an exceptionally good person in a past life. A patient, selfless, saintly sort of person. So in this life, he’d been rewarded for his past goodness with heightened sensitivities. According to Violet, Will felt things more deeply and understood things most people overlooked, and this made his everyday more like Nirvana.

Josephine didn’t appreciate his sister’s interest in Eastern religion. She didn’t like the humming sound of Violet’s Tibetan singing bowl, her woodsy incense, the picture of Geshla in a glitzy gold frame on her bedside table.

The Hursts were Catholic. Whenever Violet sat cross-legged with a strand of mala beads, Josephine told her to put away her “faux rosary.” Back in August, Violet had shaved off all her hair with their father’s electric beard trimmer. Will remembered Douglas storming into the family room, a long brown wisp threaded through his fingers, shouting, “Violet! What is the meaning of this ?!” Without so much as turning her bald head away from her guided-meditation DVD, Violet had said: “Meanings are the illusion of a deluded mind, Dad. Stop trying to squeeze reality into a verbal shape.”

Читать дальше