The cortège snaked its way through the corridors of the palace and out into the courtyard, the various bodies taking their appointed seats. The members of the legislative chambers had already taken theirs. They wore costumes similar to that of the Directors, the ‘Roman’ look in their case sitting uneasily with their four-cornered caps, which were David’s homage to the heroes of the Polish revolution of 1794.

Having taken their seats, the Directors despatched an official to usher in the principal actors of the day’s festivities. The airs beloved of the French Republic had been superseded by a symphony performed by the orchestra of the Conservatoire, but this was rudely interrupted by shouts of ‘ Vive Bonaparte! ’, ‘ Vive la Nation! ’, ‘ Vive le libérateur de l’Italie! ’ and ‘ Vive le pacificateur du continent! ’ as a group of men entered the courtyard.

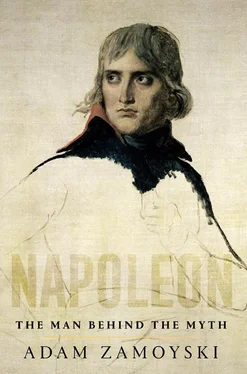

First came the ministers of war and foreign relations in their black ceremonial costumes. They were followed by a diminutive, gaunt figure in uniform, his lank hair dressed in the already unfashionable ‘dog’s ears’ flopping on either side of his face. His gauche movements ‘charmed every heart’, according to one onlooker. He was accompanied by three aides-de-camp, ‘all taller than him, but almost bowed by the respect they showed him’. There was a religious silence as the group entered the courtyard. Everyone present stood and uncovered themselves. Then the cheering broke out again. ‘The present elite of France applauded the victorious general, for he was the hope of everyone: republicans, royalists, all saw their present and future salvation in the support of his powerful arm.’ The dazzling military victories and diplomatic triumph he had achieved contrasted so strikingly with his puny stature, dishevelled appearance and unassuming manner that it was difficult not to believe he was inspired and guided by some higher power. The philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt was so impressed when he saw him, he thought he was contemplating an ideal of modern humanity.5

When the group reached the foot of the altar of the fatherland, the orchestra and choir of the Conservatoire struck up a ‘Hymn to Liberty’ composed by François-Joseph Gossec to the tune of the Catholic Eucharistic hymn O Salutaris Hostia , and the crowd joined in an emotionally charged rendition of what the official account of the proceedings described as ‘this religious couplet’. The Directors and assembled dignitaries took their seats, with the exception of the general himself. ‘I saw him decline placing himself in the chair of state which had been prepared for him, and seem as if he wished to escape from the general bursts of applause,’ recalled the English lady, who was full of admiration for the ‘modesty in his demeanour’. He had in fact requested that the ceremony be cancelled when he heard what was in store. But there was no escape.6

The Republic’s minister for foreign relations, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, limped forward in his orthopaedic shoe, his ceremonial sword and the plumes in his hat performing curious motions as he went. The President of the Directory had chosen him rather than the minister of war to present the reluctant hero. ‘It is not the general, it is the peacemaker, and above all the citizen that you must single out to praise here,’ he had written to Talleyrand. ‘My colleagues are terrified, not without reason, of military glory.’ This was true.7

‘No government has ever been so universally despised,’ an informant in France had written to his masters in Vienna only a couple of weeks before, assuring them that the first general with the courage to raise the standard of revolt would have half of the nation behind him. Many in Paris, at both ends of the political spectrum, were expecting General Bonaparte to make such a move, and in the words of one observer, ‘everyone seemed to be watching each other’. According to another, there were many present who would happily have strangled him.8

The forty-three-year-old ex-aristocrat and former bishop Talleyrand knew all this. He was used to shrouding his feelings with an impassive countenance, but his upturned nose and thin lips, curling up on the left-hand side in a way suggesting wry amusement, were well fitted to the speech he now delivered.

‘Citizen Directors,’ he began, ‘I have the honour to present to the executive Directory citizen Bonaparte, who comes bearing the ratification of the treaty of peace concluded with the emperor.’ While reminding those present that the peace was only the crowning glory of ‘innumerable marvels’ on the battlefield, he reassured the shrinking general that he would not dwell on his military achievements, leaving that to posterity, secure in the knowledge that the hero himself viewed them not as his own, but as those of France and the Revolution. ‘Thus, all Frenchmen have been victorious through Bonaparte; thus his glory is the property of all; thus there is no republican who cannot claim his part of it.’ The general’s extraordinary talents, which Talleyrand briefly ran through, were, he admitted, innate to him, but they were also in large measure the fruit of his ‘insatiable love of the fatherland and of humanity’. But it was his modesty, the fact that he seemed to ‘apologise for his own glory’, his extraordinary taste for simplicity, worthy of the heroes of classical antiquity, his love of the abstract sciences, his literary passion for ‘that sublime Ossian ’ and ‘his profound contempt for show, luxury, ostentation, those paltry ambitions of common souls’ that were so striking, indeed alarming: ‘Oh! far from fearing what some would call his ambition, I feel that we will one day have to beg him to give up the comforts of his studious retreat.’ The general’s countless civic virtues were almost a burden to him: ‘All France will be free: it may be that he will never be, that is his destiny.’9

When the minister had concluded, the victim of destiny presented the ratified copy of the peace treaty to the Directors, and then addressed the assembly ‘with a kind of feigned nonchalance, as though he were trying to intimate that he little liked the regime under which he was called to serve’, in the words of one observer. According to another, he spoke ‘like a man who knows his worth’.10

In a few clipped sentences, delivered in an atrocious foreign accent, he attributed his victories to the French nation, which through the Revolution had abolished eighteen centuries of bigotry and tyranny, had established representative government and roused the other two great nations of Europe, the Germans and Italians, enabling them to embrace the ‘spirit of liberty’. He concluded, somewhat bluntly, that the whole of Europe would be truly free and at peace ‘when the happiness of the French people will be based on the best organic laws’.11

The response of the Directory to this equivocal statement was delivered by its president, Paul François Barras, a forty-two-year-old minor nobleman from Provence with a fine figure and what one contemporary described as the swagger of a fencing-master. He began with the usual flowery glorification of ‘the sublime revolution of the French nation’ before moving on to vaporous praise of the ‘peacemaker of the continent’, whom he likened to Socrates and hailed as the liberator of the people of Italy. General Bonaparte had rivalled Caesar, but unlike other victorious generals, he was a man of peace: ‘at the first word of a proposal of peace, you halted your triumphant progress, you laid down the sword with which the fatherland had armed you, and preferred to take up the olive branch of peace!’ Bonaparte was living proof ‘that one can give up the pursuit of victory without relinquishing greatness’.12

Читать дальше