Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

4thestate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate 2014

Text © Rod Liddle 2014

Rod Liddle asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Cover photograph © Frantzesco Kangaris / eyevine

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN 9780007351275

Ebook Edition © May 2014 ISBN: 9780007351305

Version 2015-03-10

For Alicia

… remember that I am an ass; though it be not written down, yet forget not that I am an ass.

William Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing

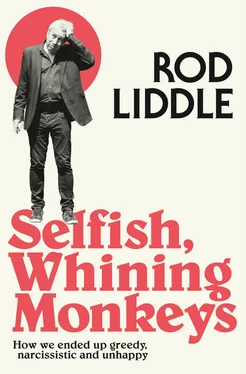

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1 Aeroplanes

2 The Tower of Arse

3 The Waiting

4 Move

5 The Culture of Narcissism

6 Married With Kids

7 Grand Theft Auto versus Boredom

8 And All Women Agree With Me About This

9 Class

10 Deference

11 Faux-Left

12 Juristocracy

13 Cloistered Elites 5, the North 0

14 Choice

15 Hairs, HAIRS, Growing Out of Your Spinal Column …

16 The Muon and the Elephant in Your Sitting Room

17 Deutsch–Amerikanische Freundschaft

The End

Index

Text Permissions

About the Publisher

Home is so sad. It stays as it was left,

Shaped to the comfort of the last to go

As if to win them back.

Philip Larkin

I got an aeroplane for Christmas when I was six years old. Not a real one, but a heavy tinplate thing with chunky red flashing plastic lights on the wings and some sort of noise box which made a sound like one of those heaving 1950s vacuum cleaners, a piercing shriek like it was undergoing a hysterectomy without anaesthetic. I’d seen it in, I think, the toy department of Selfridges in Oxford Street on the annual trip to town where I got to visit Santa’s grotto and choose my present for the year. I can remember right now standing by the counter piled up with all these unimagined and beguiling toys and seeing the aeroplane up on top, lights flashing, screaming away – a big BOAC passenger liner – and being utterly, if momentarily, captivated by it.

‘Why would you want a plane?’ my mum asked with a sort of perplexed distaste as we stood there. None of us had ever been on one, nor were likely to. Aside from the unimaginable cost and the fear of flying, my family didn’t really hold with abroad on account of it being too hot and full of wogs. My dad had been abroad only once, briefly, to shell bits of Belgium during those interminable, drawn-out final stages of the Second World War. I still have a replica of the MTB he served on, carved with rough approximation to detail out of the brass casing of a German shell which had hit his boat but – mercifully, for my dad and by extension me – not detonated. They shelled Belgium after it had been liberated, according to my dad, because they simply couldn’t abide the Belgians, devious and bitter people and, if we’re being honest, far, far, worse than the Krauts. So in early 1945 Dad’s MTB anchored in some Belgian port, I forget which, and took potshots at the church tower from the stern cannon, and when they went onshore they pissed in the streets because that’s what the Belgians were habituated to, apparently. Awful people, almost as bad as the French.

Many years later, when I went on a work trip to Antwerp, I kept my eyes trained upwards in case they started throwing buckets of piss out of the windows, as my dad gravely assured me they would. No proper sanitation in Belgium, you see – an echo, in my dad’s mind, of John Betjeman’s bitter little list of stuff which made Britain distinct:

Free speech, free passes, class distinction,

Democracy and proper drains.

My mum had never been abroad, not even to kill people. A little later, in the early 1970s, she said she quite fancied visiting Egypt because they were at war with Israel and she didn’t much like Jews. But she never went.

So, anyway, after this short cross-examination in Selfridges I got my plane, pulled off the wrapping paper on Christmas Day and ran around the house with the thing with its lights on and the engine making that fucking demented noise, swooping down every so often to attack our amiable half-breed dog Skipper who, after a few moments of this torment, bit me deeply on the arm and then cowered behind the settee, tail wrapped underneath his arse and backbone curved almost in a semi-circle, because he knew he was in the shit, with me howling holding up my arm for all to see. And yet as it turned out Skipper was exonerated, my mother correctly assuming that the dog had been provoked beyond all reasonable limits and I had got what I deserved. So I stood there crying at the injustice of it all while Skipper – out of contrition or hunger, who knows? – licked away at the blood still pouring from the gash on my arm, the edges of the wound slightly blueish where his dumb and blunt half-Labrador teeth had merely bruised, rather than cut. But the licking was OK, because dogs’ tongues were antiseptic, according to my mum. ‘Better than Germolene, a dog’s tongue. You don’t need a bandage,’ she had said. I don’t know why, but I’ll always remember that purple-blue colour around the wound. It seemed exotic and in some way more severe, more of a grown-up wound, than if it had just been blood.

The plane lasted maybe three days before the huge clunking batteries gave out and my interest in swooping around with it – carefully avoiding the dog now – gave out too. And I had a sense, by about tea-time on 28 December 1966, when the family at last scuttled itself gratefully back from the sitting room – which would next be used twelve months hence; hell, you could still smell the pine needles in June – to the warm cluttered chaos of the parlour, that it had been a wasted opportunity, this growling, flashing plane. One trip to London every year – we lived twelve or thirteen miles away in Bexleyheath, and my dad worked in town during the week, but aside from Christmas we never, ever, went in ourselves – and one big present every year, and I’d chosen this thing that just made a noise and flashed its lights. I wasn’t sure what I should have chosen, but the plane definitely wasn’t it. The plane was, I thought to myself silently, shite.

Its very shiteness, of course, is why it sticks in the memory, a forlorn disappointment and also a warning. It nags away at me now when I buy presents for my own kids and they express the mildest interest in something which I know will hold their attention only briefly and will consequently be, for them, a source of long regret. Toys which are flashy, superficial and demand nothing from their owners, like those rides at Alton Towers or Thorpe Park in which you queue for hours to be strapped down and flung somewhere for twenty seconds, maybe through water if you’re lucky, and you end up wondering what the fuck it was all about, all that waiting, with the furious wasps buzzing around a thousand hideous onesies smeared with ketchup and the dried-out sugar from soft drinks and the whining, the incessant whining, about how long we have to wait for stuff.

Читать дальше