SUMMER OF BLOOD

The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381

DAN JONES

For my parents

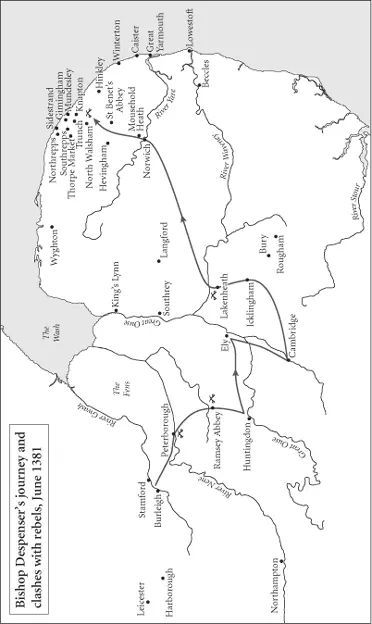

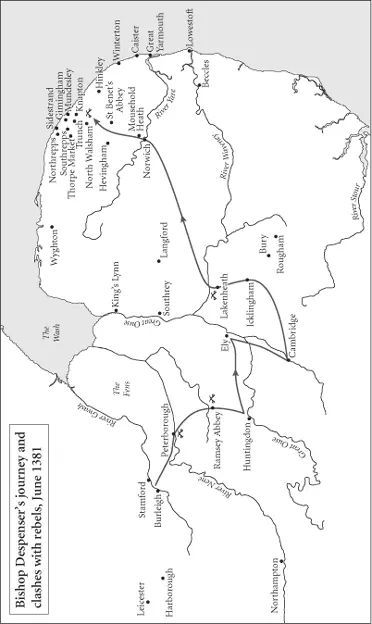

Maps MAPS Rebellious towns in Essex and Kent, May and early June 1381 Bishop Despenser’s journey and clashes with rebels, June 1381

Foreword

Introduction

Part I

Chapter One - Parliament

Chapter Two - Lancaster

Chapter Three - Collections

Chapter Four - A Call to Arms

Chapter Five - A General and A Prophet

Part II

Chapter Six - Blackheath

Chapter Seven - The True Commons

Chapter Eight - The Bridge

Chapter Nine - First Flames

Chapter Ten - Under Siege

Chapter Eleven - War Council

Chapter Twelve - Mile End

Chapter Thirteen - The Tower

Chapter Fourteen - The Rustics Rampant

Chapter Fifteen - Crisis

Chapter Sixteen - Smithfield

Chapter Seventeen - Showdown

Part III

Chapter Eighteen - Retribution

Chapter Nineteen - The Bishop

Chapter Twenty - Counter-Terror

Chapter Twenty-One - Norwich

Chapter Twenty-Two - Vengeance

Epilogue

Notes

Author’s Note

Index

A Note on Sources

Copyright

About the Publisher

MAPS CONTENTS Maps MAPS Rebellious towns in Essex and Kent, May and early June 1381 Bishop Despenser’s journey and clashes with rebels, June 1381 Foreword Introduction Part I Chapter One - Parliament Chapter Two - Lancaster Chapter Three - Collections Chapter Four - A Call to Arms Chapter Five - A General and A Prophet Part II Chapter Six - Blackheath Chapter Seven - The True Commons Chapter Eight - The Bridge Chapter Nine - First Flames Chapter Ten - Under Siege Chapter Eleven - War Council Chapter Twelve - Mile End Chapter Thirteen - The Tower Chapter Fourteen - The Rustics Rampant Chapter Fifteen - Crisis Chapter Sixteen - Smithfield Chapter Seventeen - Showdown Part III Chapter Eighteen - Retribution Chapter Nineteen - The Bishop Chapter Twenty - Counter-Terror Chapter Twenty-One - Norwich Chapter Twenty-Two - Vengeance Epilogue Notes Author’s Note Index A Note on Sources Copyright About the Publisher

Rebellious towns in Essex and Kent,

May and early June 1381

Bishop Despenser’s journey and clashes

with rebels, June 1381

FOREWORD CONTENTS Maps MAPS Rebellious towns in Essex and Kent, May and early June 1381 Bishop Despenser’s journey and clashes with rebels, June 1381 Foreword Introduction Part I Chapter One - Parliament Chapter Two - Lancaster Chapter Three - Collections Chapter Four - A Call to Arms Chapter Five - A General and A Prophet Part II Chapter Six - Blackheath Chapter Seven - The True Commons Chapter Eight - The Bridge Chapter Nine - First Flames Chapter Ten - Under Siege Chapter Eleven - War Council Chapter Twelve - Mile End Chapter Thirteen - The Tower Chapter Fourteen - The Rustics Rampant Chapter Fifteen - Crisis Chapter Sixteen - Smithfield Chapter Seventeen - Showdown Part III Chapter Eighteen - Retribution Chapter Nineteen - The Bishop Chapter Twenty - Counter-Terror Chapter Twenty-One - Norwich Chapter Twenty-Two - Vengeance Epilogue Notes Author’s Note Index A Note on Sources Copyright About the Publisher

‘A revell! A revell!’ 1

No one could forget the noise when Wat Tyler led his ragtag army of roofers and farmers, bakers, millers, ale-tasters and parish priests into the City of London on a crusade of bloodthirsty justice. It filled the City for days: frantic screaming and cries of agony that accompanied acts of butchery and chaos. It was as if, thought one observer, all the devils in hell had found some dark portal and flooded into the City. 2

Tyler’s army screamed on Corpus Christi, the morning on which they stormed over London Bridge and swarmed from the streets of Southwark, leaving smouldering brothels and broken houses behind them as they headed for the streets of the capital. They howled with demented joy when they sacked and burned down the Savoy-one of the greatest palaces in Europe and the pride of England’s most powerful nobleman. They screeched like peacocks when they dragged royal councillors from the Tower and beheaded them, and again when they joined native Londoners in pulling terrified Flemish merchants from their sanctuary inside churches and hacking them to death in the streets.

The great rebellion of summer 1381, driven by the mysterious general Wat Tyler and the visionary northern preacher John Ball, was one of the most astonishing events of the later Middle Ages. A flash rising of England’s humblest men and women against their richest and most powerful countrymen, it was organised in its early stages with military precision and ended in chaos.

Between May and August rebellion swept through virtually the entire country. It was sparked by a series of three poll taxes, each more recklessly imposed than the last, and all played out against a background of oppressive labour laws that had been imposed to keep the rich rich and the poor poor. But more broadly the rebellion was aimed at what many ordinary people in England saw as a long and worsening period of corrupt, incompetent government and a grievous lack of social justice. Like most rebellions, it was the sum of many murky parts. There was a radical cabal at the centre proposing a total overhaul of the organisation of English government and lordship. Their zeal swept along thousands of honest but discontented working folk who agreed with the general sentiment that things, in general, ought to be better. And at the fringes there were many opportunistic plunderers, disgruntled score-settlers and the incorrigibly criminal, to whom any opportunity for violence and theft was welcome. 3

The rebellion’s focal point and moment of high drama came in London on the festival weekend of Thursday 13 to Sunday, 16 June. On that weekend a crowd of thousands, who had marched to London from the Kentish capital of Canterbury on a sort of anti-pilgrimage, joined with an excited mob drawn from the common people of the capital to demonstrate, riot and pass judgement on their rulers. They came within a whisker of taking down the entire royal government. London, which had been riven with faction and anti-government sentiment for nearly five years, collapsed into anarchy within hours of the rebels’ arrival on the south bank of the River Thames. Finding no shortage of allies within its walls, the rebels achieved in an astonishingly short time the total paralysis of government, the terrorisation of the most important men in the state and the destruction of the Savoy Palace and many other beautiful buildings. Public order dissolved, and was restored only at the highest cost to the Crown. And after a period of what amounted to military rule across London, the country remained at risk of terror from within for months, first fearing a repeat of the rebellion, and subsequently brutalised by a judicial counter-terror that lasted for most of the rest of the year. It would change the course of English history for ever.

Читать дальше