COPYRIGHT

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Ebook First Edition 2016

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2016

www.thetimes.co.uk

Ebook Edition © September 2016

ISBN: 9780008222574, version 2016-10-13

The Times is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

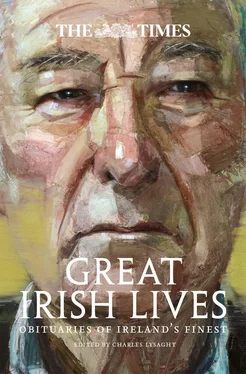

Cover Image:

“From Everywhere and Nowhere (Seamus Heaney)”

Colin Davidson b. 1968 © Colin Davidson. 2013 Collection Ulster Museum

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Henry Grattan

Daniel O’Connell

Maria Edgeworth

Tom Moore

Father Mathew

William Dargan

Earl of Rosse

Cardinal Cullen

Charles Stewart Parnell

Sir John Pope Hennessy

Mrs Cecil Alexander

Oscar Wilde

Lord Morris of Spiddal

Archbishop Croke

Michael Davitt

The O’Conor Don

Sir W. H. Russell

John Millington Synge

Sir Luke O’Connor

John Redmond

Cardinal Gibbons

Michael Collins

Erskine Childers

Thomas Crean V. C.

Lord Pirrie

Lord MacDonnell

Kevin O’Higgins

Countess Markievicz

John Devoy

John Woulfe Flanagan

T. P. O’Connor

Sir Horace Plunkett

Lady Gregory

George Moore

Edward Carson

William Butler Yeats

Sir John Lavery

James Joyce

Sarah Purser

John McCormack

Douglas Hyde

Edith Somerville

John Dulanty

Evie Hone

William Francis Casey

Margaret Burke Sheridan

Archbishop Gregg

Sean O’Casey

Jimmy O’Dea

William T. Cosgrave

Frank O’Connor

Lady Hanson

Sean Lemass

Lord Brookeborough

George O’Brien

Kate O’Brien

Eamon de Valera

John A. Costello

Brian Faulkner

Professor Frances Moran

Micheál Mac Liammóir

Professor F. S. L. Lyons

Anita Leslie

Frederick H. Boland

Siobhan McKenna

Eamonn Andrews

Sean MacBride

Samuel Beckett

Cardinal O Fiaich

Ernest Walton

Molly Keane

Michael O’Hehir

Dermot Morgan

Jack Lynch

Rev. F. X. Martin

Sister Genevieve O’Farrell

Maureen Potter

Mary Holland

Joe Cahill

Bob Tisdall

George Best

John McGahern

Charles Haughey

Sam Stephenson

David Ervine

Tommy Makem

Conor Cruise O’Brien

Vincent O’Brien

Alex “Hurricane” Higgins

Dr Garret FitzGerald

Declan Costello

The Knight of Glin

Mary Raftery

Aengus Fanning

Louis Le Brocquy

Maire MacSwiney Brugha

Maeve Binchy

Seamus Heaney

Albert Reynolds

The Rev. Ian Paisley

Jack Kyle

Brian Friel

Maureen O’Hara

Sir Terry Wogan

Searchable Terms

Footnotes

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Charles Lysaght

WHEN DR JOHNSON proclaimed the Irish an honest race because they seldom spoke well of one another, he should have made it clear that it was the reputations of the living that he had in mind. In Ireland, speaking of the dead in the aftermath of their demise, the adage nihil nisi bonum applies not only among friends and acquaintances but in the media. Readers of Irish newspapers, national and especially local, are treated to accounts of the unprecedented gloom that settled over the district where the deceased lived, the largest and most representative gathering at a funeral within living memory, accompanied by eulogies reciting how the dear departed thought only of others and never of themselves, were never known to say an unkind word about anybody, were devoted to their family, were exemplary in their piety and charity and were universally loved and respected. Such undiscriminating eulogies lack credibility and do their subjects no favours.

It has been a signal service rendered by The Times to provide accounts of deceased Irish persons that aspire to more realism and more balance in their assessments while bringing out the exceptional achievements and positive qualities that make the deceased worthy of notice in a newspaper outside their own country. In the absence of a comprehensive dictionary of Irish biography they have sometimes been the best accounts of a person’s life, at least for a period, and, as such, a valuable reference for historians.

It has been helpful to this process that many of these obituaries are prepared in advance and so allow for checking facts and for reflection unaffected by the immediate surge of sympathy surrounding a death.

It is conducive to frankness that obituaries are published anonymously and that the identity of the authors will not be disclosed by the paper in their lifetime, so keeping faith with the nineteenth century description of The Times as ‘the most obstinately anonymous newspaper in the World’. It may add to the authority of a piece that it seems to represent the views of a great newspaper rather than an individual author. It probably puts some pressure on the individual authors to reflect a general view of a person rather than to indulge a personal experience or assessment.

Obituaries (especially major ones) may first be prepared when their subjects are relatively young and so need revision many times before publication. Apart from new facts, what is interesting about a person’s life can change quite rapidly. In the nature of things, the subject sometimes outlives the original author and what emerges on the final day is a composite work.

Historically, Irish obituaries in The Times reflected somewhat the troubled relationship that the paper had with Ireland from the days of Daniel O’Connell up to the creation of the independent Irish state. The difficulties in the relationship might even be traced back further to the incident when Irishman Barry O’Meara, who had been removed by the British Government from his role as physician to the captive Napoleon on St Helena, horse-whipped William Walter, mistaking him for his brother John who was one of the proprietors and the responsible editor of the paper. O’Meara had been affronted because The Times had dismissed as a lie a statement in his memoirs that he had been told by the deposed Emperor that The Times was in the pay of the exiled Bourbons. It ended up in court with O’Meara getting away with a fulsome apology.

Читать дальше