Table of Contents

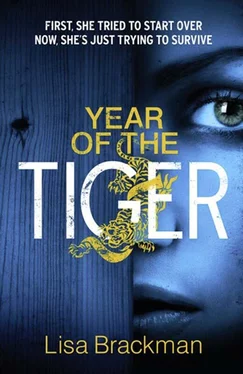

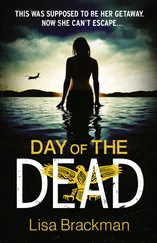

Cover

Title page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for Year of the Tiger

Copyright

About the Publisher

I’m living in this dump in Haidian Qu, close to Wudaokou, on the twenty-first floor of a decaying high-rise. The grounds are bare; the trees have died; the rubber tiles on the walkways, in their garish pink and yellow, are cracked and curling. The lights have been out in the lobby since I moved in; they never finished the interior walls in the foyers outside the elevator, and the windows are boarded up, so every time I step outside the apartment door I’m in a weird twilight world of bare cement and blue fluorescent light.

The worst thing about the foyer is that I might run into Mrs Hua, who lives next door with her fat spoiled-brat kid. She hates that I’m crashing here, thinks I’m some slutty American who is corrupting China’s morals. She’s always muttering under her breath, threatening to report me to the Public Security Bureau for all kinds of made-up shit. It’s not like I ever did anything to her, and it’s not like I’m doing anything wrong, but the last thing I need is the PSB on my ass.

I’ve got enough problems.

Outside, the afternoon sun filters through a yellow haze. My leg hurts, but I should walk, I tell myself. Get some PT in. The deal I make with myself is, if it gets too bad, I’ll take a Percocet; but I only have about a dozen left, so it has to be really bad before I can take one. Today the pain is just a dull throb, like a toothache in my thigh.

I pass the gas tanks off Chengfu Road, these four-story-high giant globes, and I think: one of these days, some guy will get pissed off at his girlfriend, light a couple sticks of dynamite underneath them (since they don’t have many guns here, the truly pissed-off tend to vent with explosives and rat poison), a few city blocks and a couple thousand people will get incinerated, and everyone will shrug – oh, well, too bad, but this is China, and shit happens. Department store roofs collapse; chemicals poison rivers; miners suffocate in illegal mines. I walk down this one block nearly every day on my way to work, and there are five sex businesses practically next door to each other, ‘teahouses’ and ‘foot massage parlors,’ with girls from the countryside sitting on pink leatherette couches, waiting for some horny migrant worker to come in with enough renminbi to fuck his brains out for a while and forget about the shack he’s living in and the family he’s left behind and the shitty wages he’s earning. Hey, why not?

I still like it here, overall.

I guess.

I’m just in this bad mood lately.

So I call Lao Zhang. That’s what I do these days when I’m feeling sorry for myself.

‘ Wei ?’ Lao Zhang has a growly voice, like he’s talking himself out of a grunt half the time.

‘It’s me. Yili.’

That’s my Chinese name, Yili. It means ‘progressive ideas’ or something. Mainly it sounds kind of like Ellie.

‘Yili, ni hao .’

He sounds distracted, which isn’t like him. He’s probably working; he almost always is. He’s been painting a lot lately. Before that, he mostly did performance pieces, stuff like stripping naked and painting himself red on top of the Drum Tower or steering a reed boat around the Houhai lakes with a life-size statue of Chairman Mao in the prow.

But usually when I call, he sounds like he’s glad to hear my voice, no matter what he’s doing. Which is one of the reasons I call him when I’m having a bad day.

‘Okay, I guess,’ I answer. ‘I’m not working. Thought I’d see what you were up to.’

‘Ah. The usual,’ he says.

‘Want some company?’

Lao Zhang hesitates.

It’s a little weird. I can’t think of a time when I’ve called that he hasn’t invited me over. Even times when I don’t want to leave my apartment, when I just want to hear a friendly voice, he’ll always try and talk me into coming out; and sometimes when I won’t, he’ll show up at my door a couple hours later with takeout and cold Yanjing beer. He’s that kind of person. He works hard, but he likes hanging out too, as long as you don’t mind him working part of the time. And I don’t. A lot of times I’ll sit on the sagging couch in his studio while he paints, listening to my iPhone, drinking beer, surfing on his computer. I like watching him paint too, the way he moves, relaxed but in control. It feels comfortable, him painting, me sitting there.

‘Sure,’ he finally says. ‘Why don’t you come over?’

‘You sure you’re not too busy?’

‘No, come over. There’s a performance tonight at the Warehouse. Should be fun. Call me when you’re close.’

Maybe I shouldn’t go, I think, as I swipe my yikatong card at the Wudaokou light rail station. Maybe he’s seeing somebody else. It’s not like we’re a couple. Even if it feels like we are one sometimes.

Sure, we hang out. Occasionally fuck. But he could do a lot better than me.

‘Lao’ means ‘old,’ but Lao Zhang’s not really old. He’s maybe thirteen, fourteen years older than I am, around forty. They call him ‘Lao’ Zhang to distinguish him from the other Zhang, who’s barely out of his teens and is therefore ‘Xiao’ Zhang, also an artist at Mati Village, the northern suburb of Beijing where Lao Zhang lives.

Before I came to China, I’d hear ‘suburb’ and think tract homes and Wal-Marts. Well, they have Wal-Marts in Beijing and housing tracts – Western-style, split-level, three bedroom, two bath houses with lawns and everything, surrounded by gates and walls. Places with names like ‘Orange County’ and ‘Yosemite Falls,’ plus my personal favorite, ‘Merlin Champagne Town.’

But Mati Village isn’t like that.

Getting to Mati Village is kind of a pain. It’s out past the 6th Ring Road, and you can’t get all the way there by subway or light rail, even with all the lines they built for the ’08 Olympics. From Haidian, I have to take the light rail and transfer to a bus.

It’s not too crazy a day. The yellow loess dust has been drowning Beijing like some sort of pneumonia in the city’s lungs, typical for spring in spite of all those trees the government’s planted in Inner Mongolia the last dozen years. The dust storms died down last night, but people still aren’t venturing out much. So I score a seat on the bench by the car door, let the train’s rhythms rattle my head. I close my eyes and listen to the recorded announcement of the stations, plus that warning to ‘watch your belongings and prepare well’ if you are planning to exit. All around me, cell phones chime and sing, extra-loud so the people plugged into iPods can still hear them.

The nongmin don’t have iPods. The migrants from the countryside are easy to spot: tanned, burned faces; bulging nylon net bags with faded stripes; patched cast-off clothes; strange, stiff shoes. But it’s the look on their faces that really gives them away. They are so lost. I fit in better here than they do.

Читать дальше