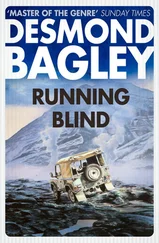

It was into this wilderness, the Odádahraun, as remote and blasted as the surface of the moon, that we went. The name, loosely translated, means ‘Murderers’ Country’. and was the last foothold of the outlaws of olden times, the shunned of men against whom all hands were raised.

There are tracks in the Odádahraun – sometimes. The tracks are made by those who venture into the interior; most of them scientists – geologists and hydrographers – few travel for pleasure in that part of the Óbyggdir. Each vehicle defines the track a little more, but when the winter snows come the tracks are obliterated – by water, by snow avalanche, by rock slip. Those going into the interior in the early summer, as we were, are in a very real sense trail blazers, sometimes finding the track anew and deepening it a fraction, very often not finding it and making another.

It was not bad during the first morning. The track was reasonable and not too bone-jolting and paralleled the Jökulsá á Fjöllum which ran grey-green with melt water to the Arctic Ocean. By midday we were opposite Mödrudalur which lay on the other side of the river, and Elin broke into that mournfully plaintive song which describes the plight of the Icelander in winter: ‘Short are the mornings in the mountains of Mödrudal. There it is mid-morning at daybreak.’ I suppose it fitted her mood; I know mine wasn’t very much better.

I had dropped all thoughts of giving Elin the slip. Slade knew that she had been in Asbyrgi – the bug planted on the Land-Rover would have told him that – and it would be very dangerous for her to appear unprotected in any of the coastal towns. Slade had been a party to attempted murder and she was a witness, and I knew he would take extreme measures to silence her. As dangerous as my position was she was as safe with me as anywhere, so I was stuck with her.

At three in the afternoon we stopped at the rescue hut under the rising bulk of the great shield volcano called Herdubreid or ‘Broad Shoulders’. We were both tired and hungry, and Elin said, ‘Can’t we stop here for the day?’

I looked across at the hut. ‘No,’ I said. ‘Someone might be expecting us to do just that. We’ll push on a little farther towards Askja. But there’s no reason why we can’t eat here.’

Elin prepared a meal and we ate in the open, sitting outside the hut. Halfway through the meal I was in mid-bite of a herring sandwich when an idea struck me like a bolt of lightning. I looked up at the radio mast next to the hut and then at the whip antenna on the Land-Rover. ‘Elin, we can raise Reykjavik from here, can’t we? I mean we can talk to anyone in Reykjavik who has a telephone.’

Elin looked up. ‘Of course. We contact Gufunes Radio and they connect us into the telephone system.’

I said dreamily, ‘Isn’t it fortunate that the transatlantic cables run through Iceland? If we can be plugged into the telephone system there’s nothing to prevent a further patching so as to put a call through to London.’ I stabbed my finger at the Land-Rover with its radio antenna waving gently in the breeze. ‘Right from there.’

‘I’ve never heard of it being done,’ said Elin doubtfully.

I finished the sandwich. ‘I see no reason why it can’t be done. After all, President Nixon spoke to Neil Armstrong when he was on the moon. The ingredients are there – all we have to do is put them together. Do you know anyone in the telephone department?’

‘I know Svein Haraldsson,’ she said thoughtfully.

I would have taken a bet that she would know someone in the telephone department; everybody in Iceland knows somebody. I scribbled a number on a scrap of paper and gave it to her. ‘That’s the London number. I want Sir David Taggart in person.’

‘What if this … Taggart … won’t accept the call?’

I grinned. ‘I have a feeling that Sir David will accept any call coming from Iceland right now.’

Elin looked up at the radio mast. ‘The big set in the hut will give us more power.’

I shook my head. ‘Don’t use it – Slade might be monitoring the telephone bands. He can listen to what I have to say to Taggart but he mustn’t know where it’s coming from. A call from the Land-Rover could be coming from anywhere.’

Elin walked over to the Land-Rover, switched on that set and tried to raise Gufunes. The only result was a crackle of static through which a few lonely souls wailed like damned spirits, too drowned by noise to be understandable. ‘There must be storms in the western mountains,’ she said. ‘Should I try Akureyri?’ That was the nearest of the four radiotelephone stations.

‘No,’ I said. ‘If Slade is monitoring at all he’ll be concentrating on Akureyri. Try Seydisfjördur.’

Contacting Seydisfjördur in eastern Iceland was much easier and Elin was soon patched into the landline network to Reykjavik and spoke to her telephone friend, Svein. There was a fair amount of incredulous argument but she got her way. ‘There’s a delay of an hour,’ she said.

‘Good enough. Ask Seydisfjördur to contact us when the call comes through.’ I looked at my watch. In an hour it would be 3:45 p.m. British Standard Time – a good hour to catch Taggart.

We packed up and on we pushed south towards the distant ice blink of Vatnajökull. I left the receiver switched on but turned it low and there was a subdued babble from the speaker.

Elin said, ‘What good will it do to speak to this man, Taggart?’

‘He’s Slade’s boss,’ I said. ‘He can get Slade off my back.’

‘But will he?’ she asked. ‘You were supposed to hand over the package and you didn’t. You disobeyed orders. Will Taggart like that?’

‘I don’t think Taggart knows what’s going on here. I don’t think he knows that Slade tried to kill me – and you. I think Slade is working on his own, and he’s out on a limb. I could be wrong, of course, but that’s one of the things I want to get from Taggart.’

‘And if you are wrong? If Taggart instructs you to give the package to Slade? Will you do it?’

I hesitated. ‘I don’t know.’

Elin said. ‘Perhaps Graham was right. Perhaps Slade really thought you’d defected – you must admit he would have every right to think so. Would he then …?’

‘Send a man with a gun? He would.’

‘Then I think you’ve been stupid, Alan; very, very stupid. I think you’ve allowed your hatred of Slade to cloud your judgment, and I think you’re in very great trouble.’

I was beginning to think so myself. I said, ‘I’ll find that out when I talk to Taggart. If he backs Slade … ’ If Taggart backed Slade then I was Johnny-in-the-middle in danger of being squeezed between the Department and the opposition. The Department doesn’t like its plans being messed around, and the wrath of Taggart would be mighty.

And yet there were things that didn’t fit – the pointlessness of the whole exercise in the first place, Slade’s lack of any real animosity when I apparently boobed, the ambivalence of Graham’s role. And there was something else which prickled at the back of my mind but which I could not bring to the surface. Something which Slade had done or had not done, or had said or had not said – something which had rung a warning bell deep in my unconscious.

I braked and brought the Land-Rover to a halt, and Elin looked at me in surprise. I said, ‘I’d better know what cards I hold before I talk to Taggart. Dig out the can-opener – I’m going to open the package.’

‘Is that wise? You said yourself that it might be better not to know.’

‘You may be right. But if you play stud poker without looking at your hole card you’ll probably lose. I think I’d better know what it is that everyone wants so much.’

Читать дальше