Apart from the considerable duplication of effort this system dictated, not to mention the restrictions it sometimes placed on the types of accommodation we deemed acceptable, it struck an unwelcome, discordant note among our hosts and anybody else who was taking an interest. I sometimes felt we were arriving with our dirty laundry already on display.

In the mornings they would emerge from separate quarters like boxers from opposing corners of the ring, except that, unlike boxers governed by the bell, they could stage their entrances for effect. Sometimes she would keep him waiting, sometimes vice versa. Tension that might have been safely – if uncomfortably – vented behind closed doors was carried instead into the day’s work, where it could fester.

It was like a secret deformity that our hosts never saw, but which restricted our freedom to programme joint activities while doubling much of the administrative effort. Even something as simple as getting the end-of-tour presentation photographs signed by them both could call upon all Harold Brown’s skills as the behind-the-scenes co-ordinator. Never were his talents as butler/diplomat in greater demand than when he had to preside over divided domestic quarters in an unfamiliar house.

There were benefits as well. One of the unresolved questions in the wake of their divorce was whether the Prince and Princess should have tried harder to ‘make a go of it’. Looking at the situation from a different aspect, the question could be rephrased, ‘How long should you force people to stay together if they want to be apart?’

As I greeted the Princess in the mornings or took my leave at night, I knew the answer in practical if not in philosophical terms. There was absolutely no doubt that, however sadly solitary, her room was a haven of privacy between bouts of exhausting public exposure. Had she been forced to swap the media spotlight by day for a marital battleground by night, I doubt she would have performed her royal duties at all. Since I observed similar feelings in the Prince, it is safe to conclude that, this close to the end of their marriage, the royal double act was a performance best reserved for barely consenting adults in public only.

Other benefits looked attractive at first sight, especially to me as the inexperienced new equerry. On closer inspection, however, they stirred my early suspicion that my boss was anything but a guileless pretty face. These dubious benefits centred on the Princess’s wish to be seen as more popular, approachable, flexible and generally ‘normal’ than her husband. When they were on tour together he was conveniently close by to act as a foil for this desire, much to the uncomfortable advantage of ‘her team’.

As if to underline the contrast with the Prince’s habitually more preoccupied appearance, she would burst from her quarters in the morning radiating popularity, approachability and flexibility to the assembled entourages as we waited to depart for the day’s programme. Usually she would time it so that we had several minutes to bask in the effect and pick up the nonverbal signals with which she indicated who was in favour and who was to be conspicuously ignored.

Her husband’s staff were a favourite target. It was seldom a hardship, however. Her desire to create an impression that contrasted with her husband’s usually made her a welcome visitor to the temporary office. There she might find two of his secretaries wrestling with our primitive portable computers and last-minute amendments to the Prince’s next speech.

‘What is it today – global warming or Shakespeare?’ she would ask with a laugh, perching elegantly on a desk. Then there would be girl-talk about clothes, or the heat, or the hysterically ornate splendour of her quarters. There would always be concerned enquiries about the staff’s accommodation or general morale. Needless to say, I listened to the answers with my heart in my mouth. Any complaint would earn me a raised royal eyebrow. It all helped to prove her point: I care about the workers, even if certain other people are too busy.

She also managed to create the impression that her husband was unpunctual and lacked her enthusiasm for the day’s events. When he emerged and took in the scene, she would chide him with a thin affability. In full view of an audience she had already warmed up, he could do little to express any irritation her teasing provoked.

This often left me feeling queasy. Public point-scoring was one of the most unsettling aspects of the marital deterioration we had to witness, even if I was occasionally a temporary beneficiary. If I was obviously in favour, the resultant inner glow was tempered by the thought that she was just as likely to be trying to make someone else feel bad as to make me feel good. In turn this produced an unhealthy climate in which her praise could not be taken at face value. It also sharpened the sting of her criticism, which was seldom related to the actual gravity of the offence. Praise and criticism of her staff were both ploys she used in the mental game of musical chairs through which she played out her own emotional confusion.

Small wonder, then, that she and the Prince grew to prefer touring separately. The morning nonverbal signals indicating who was in and who was out never entirely vanished, but at least the audience was smaller. Without the need to strike a contrasting attitude to the Prince, the Princess’s actions became a more honest reflection of her own feelings – and she enjoyed herself more, which was good for everyone.

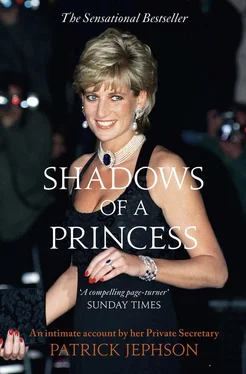

My first royal tour marked the end of my apprenticeship. There were still mountains of experience to climb. If I served her for a hundred years, I would still have much to learn about the Princess of Wales, and even more about the reactions she sparked in others. At last, however, I had the tour labels on my briefcase; I could swap tall stories with the best of them. Even more importantly, I had shared with the Princess the pressures and prolonged proximity that only foreign tours provide, especially difficult ones, which this definitely had been.

I had passed through a barrier of acceptability – one of many on the twisting and ultimately futile path to royal intimacy. From now on our relationship would be slightly different. She began to see through my mask of deference and I began to see through her saintly image.

The most significant change was the one least discussed. To travel with the Prince and Princess at that time was to learn, inescapably, the truth of their growing estrangement. In the office it had been almost possible to pretend that all was well. On the road in Britain I had been supporting only one half of what was still seen as a formidable double act. There was nothing to stop me arguing – as I did – that press speculation about problems in the marriage was offensive and inaccurate. The whole issue could be ignored in the comforting round of day-to-day business.

This was true no longer. I had arranged the separate accommodation and sweated to ensure the hermetic separation of his and her programmes, required for all but a few joint appearances. In Dubai I had been summoned into the cabin of the Princess’s departing jet to be given a farewell that was effusive and undeniably a pact of loyalty as I stayed behind with the Prince. I had witnessed with naive alarm the small, telltale signs of mutual antipathy that were soon to become public knowledge – averted eyes, defiantly uncoordinated walkabouts, competitive glad-handing.

Eventually, when she was travelling on solo tours, there was a welcome outbreak of informality in the Princess’s attitude towards me. Instead of the large numbers of their joint household who had previously paraded to greet her in the morning, she would find only me waiting at her door. I would be invited in, to steal extra breakfast, hear gossip from her phone calls, answer questions on the day’s business and compliment – or assist with – the choice of outfit. She might try three different outfits before setting off for the day and would ask my opinion on each.

Читать дальше