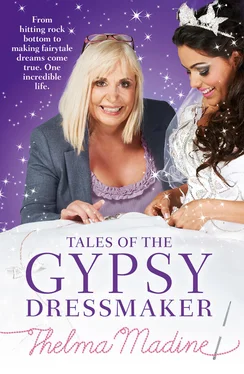

The train was so heavy it was pushing the dress forward, so I had to devise something to make it come out and over the dress. I went back to my books and decided that a bustle – a frame often used to support heavy fabric dresses in the 1800s – might be the best solution. It was trial-and-error time again.

Dave, as ever, was amazing: ‘Come on, you can do it,’ he’d say. ‘You know you can do it. You’ll work it out.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Yes, you can. I’ll help you.’

And he did. Dave always helped me make things happen.

The funny thing is, I get so many calls from people today asking how I make the dresses – ‘How do you do this bit? How can I make my bodices stay like that?’

‘You chancer!’ I want to reply. ‘It took me years to work all this stuff out. Do you think I’m just going to tell you over the phone in two minutes?’ But, of course, I just politely tell them that it’s best that they work it out for themselves as every design is different and our dresses won’t be the same as theirs.

We put the bustle under the train so that it kept the fabric up and off the back of the dress, but as soon as the girl moved in it the dress bent back in again.

Then Mary came in to see her daughter’s dress one day. She wanted more crystals on it, and I was still buying them retail as I didn’t know a supplier. So I bought two packets of Swarovski crystals – about 3,000 of them – which seemed like loads, and scattered them all over the dress.

‘Oh, no, that’s not enough, Thelma,’ she said. So I got some more.

Another day, young Mary looked at the dress. ‘I want something round the edge of the trail,’ she said. ‘I want some edging.’ Of course, she didn’t want to pay any extra for it – her mum, Gypsy Mary, was a good teacher in that respect. So I sat there night after night, stitching the edge of this train with organza and crystals – all 107 feet of it.

Finally, it was done and it was really, really heavy. In the end, I thought, ‘I’ve done what I can and that’s what she wanted. If it collapses, it collapses. There’s nothing I can do.’

But it was me who collapsed. I got really ill, probably with exhaustion. Then I got bronchitis.

Mary turned up at the house one day when I was not at all well. ‘Thelma,’ she said, ‘I want you to do an outfit for my other daughter.’

‘I can’t, Mary,’ I said. ‘Honestly, I’m just physically not up to it.’

‘Oh, it’ll be an easy one,’ she said. ‘The wedding dress is nearly done now.’

So I ended up having to do another outfit for the after-party as well. Those three months of my life were hell. I remember sitting there thinking, ‘I will never ever make another wedding dress so long as I live.’

Dave and me were invited to the wedding, but we couldn’t go as it was in Peterborough and it would have been impossible to get back in time to do the market the following day. I remember the day the family came to pick up the dresses. It was the afternoon before the wedding and I’d worked right through the night making sure it was perfect, and at about four o’clock Dave put everything in their van. As they left, Mary called me to one side.

‘Don’t tell anyone what the dress is like, or the colour of the bridesmaids’ dresses,’ she whispered. ‘And don’t mention where the wedding is.’

‘OK, Mary,’ I said. ‘That must be the hundredth time you’ve told me not to tell anybody anything.’

‘It’s just really important that no one knows about the wedding,’ she said again. But it wasn’t until some while later that I would come to realise why secrecy was important to her.

When the door closed behind them, I just sat on the end of the bed. I felt loads of things, but mostly glad that the dress was complete, and relieved that it was gone and out of the house. I didn’t have the same happy feeling that I got when I finished the kids’ dresses. I felt inadequate, to be honest, because that dress just wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t perfect. Even when it was finished it still wasn’t the way I wanted it, but there was no more time to do it. All the same I was happy knowing that young Mary was so thrilled, and her mum was so proud of her in it.

Even now I smile when I think about that bloody train. In the end, we’d had to roll the train up on a pole, like a scroll, with a handle at either end, so that they could carry it to the church and then roll it out and put it on when they got there.

That day, sitting on the bed, I could still hear Dave talking to them outside. Finally the van door slammed shut. I put my head down. I could feel my body sinking into bed. ‘This must be how you feel when you die,’ I thought. But I can’t remember what happened after that, because I slept for two days.

Someone had told the local paper about the wedding dress and its huge train, so the next time I saw it was in the paper. They’d photographed it from above, and you could see this tiny little figure at the altar and the train just going on and on and out the church door.

I must admit, when I saw it there on the page it did look good – even though it would have looked a lot better with a smaller train – and I started feeling a slight sense of achievement. It felt good to know that finally, despite everything, it was out there. It’s funny because, looking at it now, young Mary’s dress itself isn’t even big. It looks more like one of our Communion dresses.

I suppose that most people would think I was mad to carry on doing all that, but I was just so determined to rise to the challenge. Mary had pushed me, then pushed me further than I ever felt it possible to go, but also, in a way, she got me started doing what I do now. So I have a lot to thank her for, not least for teaching me about the travellers’ way of life. I’d still be doing the kids’ clothes if she hadn’t asked for that wedding dress. And all the extras that went with it.

And there was another reason for wanting to do right by Mary. All that time she came to my flat when I was making that first ever gypsy wedding dress, which she had pushed me so hard to do even when I hadn’t wanted to, and which had nearly killed me, we’d got to know each other. We told each other things and we’d become friends.

After the wedding, everyone was talking about young Mary’s wedding dress, as well as the after-party outfits and bridesmaids’ dresses we had made. Because the travellers all go to the same events and all know each other, news travels quickly. So then I started getting phone calls asking, ‘Is this the woman from Liverpool who makes the dresses?’ Then they’d say, ‘Can you make me one of these, love?’ It would be all make me this, that and the next thing. ‘I’ll send you the money, love.’

So now I had all these phone orders, which meant I had to call the travellers a lot too, and this is when I really found out that gypsies don’t communicate like settled people do. For a start they never, ever return your calls. And, on the rare occasion that they pick up, they’ll tell you that they don’t know who or what you’re talking about. ‘Oh, I don’t know her, love,’ is what they’ll say, even though you’ve talked to them face to face a hundred times before.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.