JENNY SAVILLE

Brewer Street, Oxford

26 January 2010

In light of Stanley’s eclecticism, I wrote to Gagosian, Jenny Saville’s gallery, and asked if I might have an audience with her since she seemed to represent the other end of the spectrum: a lone figure singularly preoccupied with painting flesh and the figure – solid, tangible, massive adipose studies of the body in oils.

The last I’d read, she was working in Sicily, so the approach was a bit of a punt since I wasn’t sure how I’d get out there even if she agreed to see me. However, it turned out Jenny had recently relocated to a studio in Oxford, so any thoughts of a Mediterranean adventure were quickly replaced with the more prosaic reality of a day return ticket because, to my surprise, she did agree to see me.

So one freezing Tuesday morning – satchel packed with a wine-stained notebook and a fickle Dictaphone – I caught a train. *

• • • • •

Jenny Saville’s studio is in a quiet shaded lane that belies its central city location. A two-storey building; grey-fronted and anonymous.

Lewis Carroll wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland at Christ Church College, two minutes from here. My rabbit hole is rather unprepossessing – an ashen door with a burnt-out intercom. I clatter at the letterbox and wait, stamping my feet in the cold.

Descending footsteps. Jenny opens the door and I step in. To my left is a room of large, briefly glimpsed drawings and charcoal pieces.

A set of stairs before me. We go up and Jenny makes tea.

The first floor is spacious and open plan, lit by large windows and greenhouse-like skylights. The walls are white. In front of the walls are paintings.

At the top of the stairs is a three-metre-high work of a newborn baby, the umbilical cord snaking back to a splayed vagina and soapy legs. Along from this is a trolley stand stacked with books – magazines, newspaper paint swatches, photographs and journals. Notes, clippings and articles are stuck up on the walls while other torn-out pages are filed out on the floor – creative ‘compost’ as Francis Bacon dubbed it. *

Empty cigarette packets, turned to display pictures of cancer and disease – bad teeth, laryngeal tumours, black lungs – are lined up on a dado rail.

Below the packets is a radiator that bears a painterly impression of Jenny’s bottom – a Rorschach test pattern.

The studio, as well as being large, is freezing and Jenny explains she can only work for an hour or so before she starts to seize up. The radiator is where she warms herself and takes stock:

‘This is where I stand, as you can see. I find that a cigarette is a perfect space to stand or sit and analyse what you’re doing – the length of a cigarette.’

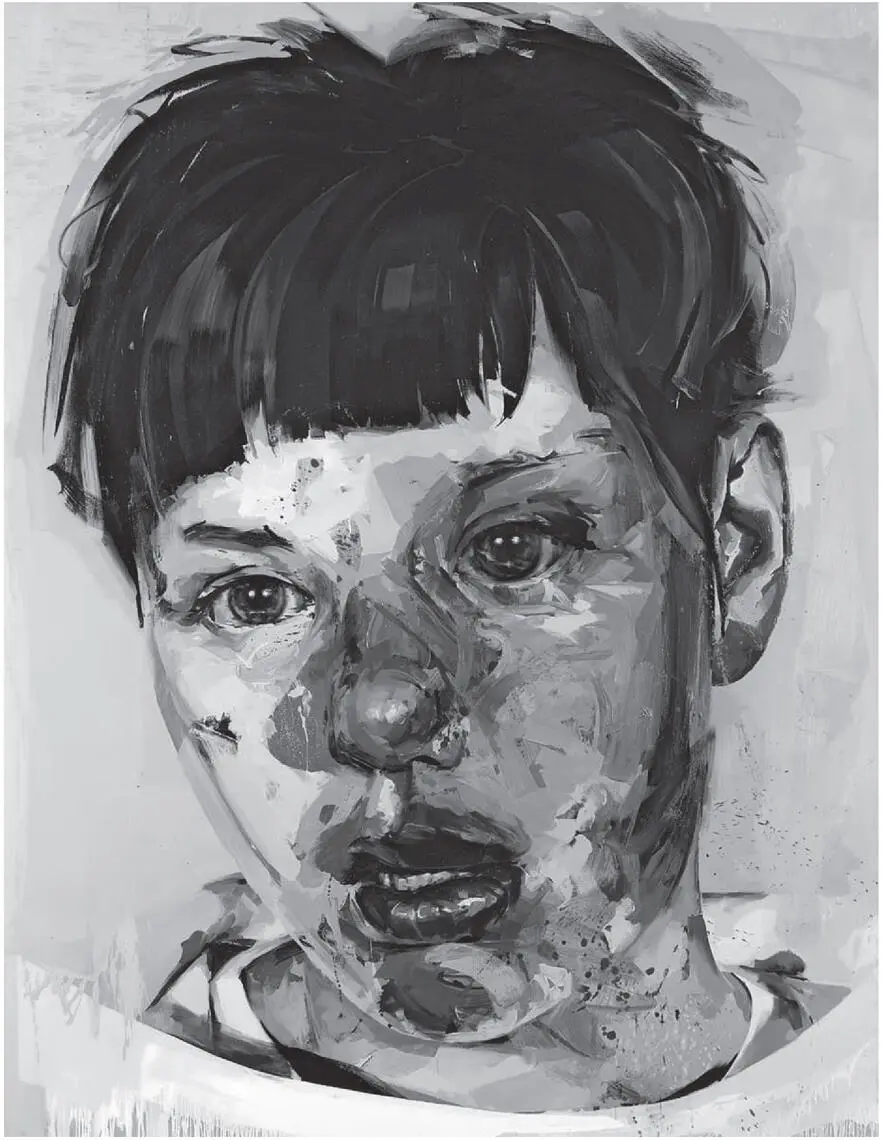

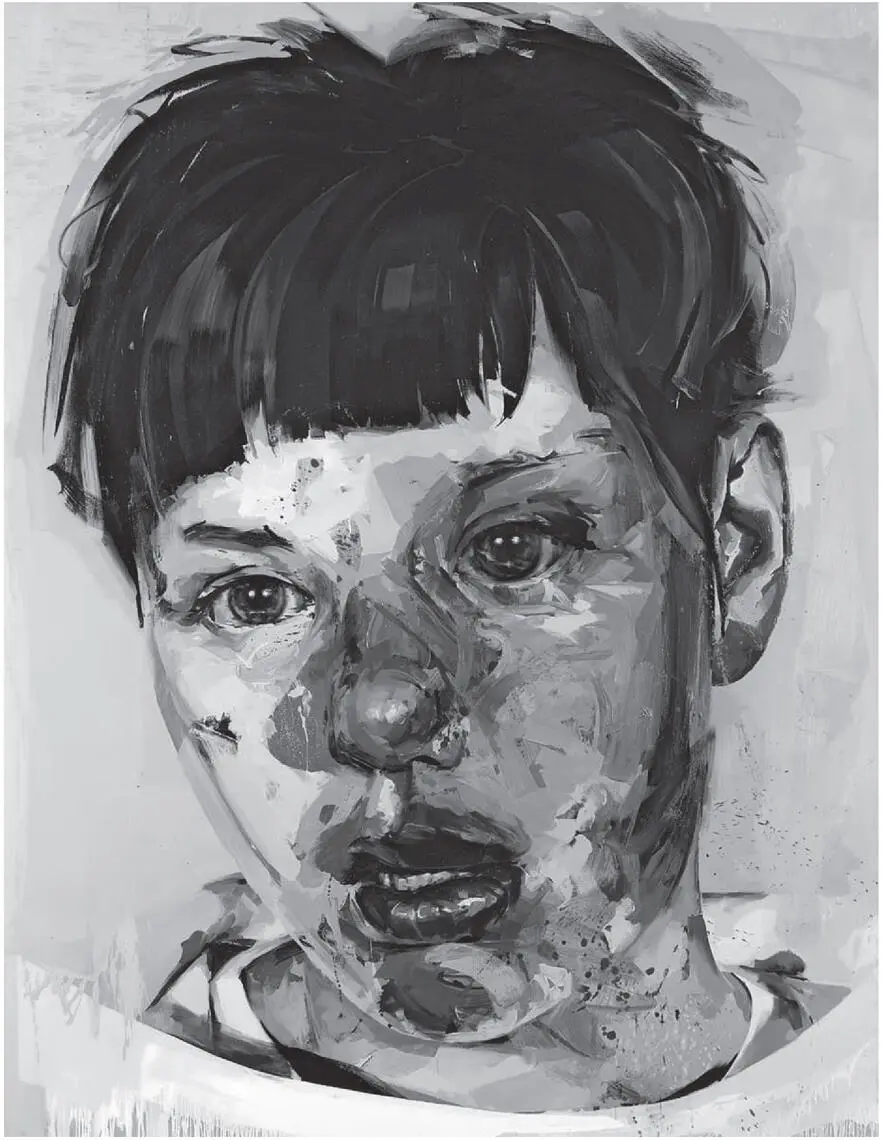

Opposite the radiator are several explorations of a single subject – a face with a mangled mouth; eyes closed, taut waxen skin lit from below, rising from a writhing, exploded mess. There are three versions of this piece, a large charcoal drawing, a mostly monochrome painted scheme – some patches of intense red and peach/pine – and an enormous black and white painting, streaked and leaking, the running paint visible below the surface layer.

None of the three is explicit about what is going on with the mouth, the wound is elusive and seemingly out of focus – a flayed moment of abstract expressionism – a de Kooning maw.

The finished piece, Witness, has recently left the studio for a London show in honour of J.G. Ballard. I’ve just missed it:

‘I think that show’s a brilliant thing to do because he was going to write my catalogue notes several times and I’ve got a lot of faxed letters from him – these great rejection letters from Ballard. (Laughs) Whenever I was asked who I’d like to write the catalogue I would always say, “Ballard. J.G. Ballard,” but first his partner was ill and then he was ill and then he wrote a fantastic summary of my work but didn’t want to write the catalogue – I’ve still got that. Everyone I’ve told about it has said, “Oh, you’ve got to publish it” – letters from Shepperton. I’ve got a really good interview with him that I taped off the radio. It’s from just after he wrote Cocaine Nights and he’s talking about the internet. Claire Walsh, his partner, was telling me how they used to watch a site where you can see the migration of swallows, a camera follows them. That was his favourite thing to watch.’ *

We sit down on a pair of paint-specked chairs and I ask about the studio, how long she’s been here, and the differences between here and her previous workspace in Palermo, Sicily.

‘In Palermo I had the guts of animals outside my studio window; the stench was amazing in the summer. That has an effect on the way you think about making work. When I first walked in here there was blossom on the trees and it had an airy feeling. I haven’t wanted to overload it so far, it’s quite pure for me to have a space like this with only the work and a few things up – normally the floor is a cascade of books, but they’re all still in boxes so I’ve quite enjoyed having a clearer head. I’ve noticed that, when I have a lot of reference material around, I tend to work a certain way, so I’ve tried to switch that around a bit and see what happens.’

Did you ever find yourself trying to get reference material into the work because it’s around you?

‘Oh yeah, I collect a lot of bits of paint, like that thing there (points to a paint-smeared newspaper). I’ve got hundreds and hundreds of those, trying to get an effect of flesh – burnt flesh or when you slide one colour into another – they become like a word-coupling or a musician putting sounds together – it all eventually feeds in.

I used to go to the Hunterian Museum in London, part of the Royal College of Surgeons. I was a member of the Pathology Society there and they used to have a room for surgeons to practise new types of operations; so there was always a room which had corpses and I used to go in and wander around; and what I loved was that each head was wrapped in a plastic bag, a Sainsbury’s bag or a Tesco bag – obviously it depended upon what part of the body the surgeons were working on – the last time I was there they were working on something to do with the spine, but all the heads, bagged up. There was something so everyday about having a Sainsbury’s bag over your head at the end of your life.’

Jenny leads me to a table of paint tubs, each different, numbered and labelled.

‘I’ve mixed these for a new piece. Because I work on such a large scale and on quite a few things at the same time, I make a series of tones and spend days studying one colour and mixing a large amount of that, shifting it so that I’ve got a core tone that can be moved around.’

Have you got huge vats of paint somewhere?

‘Big tubs of white, yes, and I use kitchen knives, big old-fashioned things to mix with. I think the maximum I’ve ever made in a day is six or seven tones. That (points to paint on a glass-topped table) will be, for example, a side cheek and a panel of the neck, so I’ll mix up two tones to go near each other – one to move your eye right back and the other to pull you forward. It started as a way of painting more abstractly, but now I’ve got certain tones that I know are going to do a job in the painting. Once I’ve got those, they’ll shift and move around. The process came out of trying to keep something fluid in a larger scale.’

Do you see these paint tones as ‘movers’ rather than colours, then? You see them in the context of the actions they’ll perform, pushing and pulling the eye – a sculptural, kinetic thing?

Читать дальше