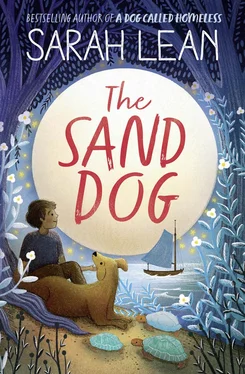

I squinted in the light until I could just make out that it was a dog. How long must he have been sitting there? He was looking out to sea, his narrow nose up in the air in a kind of proud way. He sometimes glanced over at me but when I looked at him he would look away. Then when I looked away he would shuffle a bit closer. I guessed he must want some shade because the sand was oven-hot, so I moved over and soon he came and sat next to me under the shadow of the door. He was almost as tall as I was sitting down, long and lean, with wispy fur the colour of sand. He didn’t do anything else but watch with his nose up while his ears drooped down. I wondered for a minute if he could be the third sign, but I decided he couldn’t be because he hadn’t actually come from the sea.

‘What are you waiting for?’ I said to him.

The dog’s eyes twitched towards me for a moment, but looking out over the waves was all he seemed to want to do, and we sat there for a long time, just like that, until the yellow-and-white ferry turned into the quay.

‘Gotta go,’ I said to the dog. ‘You can sit here, if you want, and keep watch for me.’ The dog looked up. ‘I’m waiting for another sign.’

At the quay, crowds of passengers disembarked.

‘Come to Uncle’s. Best restaurant on the beach,’ I said. ‘Calamari and chips. Ice-cold beer.’

I didn’t think Grandfather would really come on a Monday but you never knew, so I was still keeping an eye out for a short white-haired old man with muscular shoulders and arms, because that door was definitely telling me something. Maybe it meant that a letter from Grandfather had come! I headed into the village.

At the post office hardly anyone was queuing. I looked through the doorway to see who was inside and nearly stopped myself from going in to speak to Mrs Halimeda because she was an impatient kind of person. But when everyone else had gone I took my chance, and stepped up to the counter.

Mrs Halimeda sighed. ‘What is it this time, Azi?’

I folded one of the spare flyers, pushing it under the glass partition. ‘I couldn’t remember whether you’d seen Uncle’s new menu,’ I said.

She took it, unfolded it, and sighed again. ‘It’s exactly the same as the one you gave me last time you came in,’ she said, pushing it back through the window.

I rolled and unrolled the paper in my fingers before finally saying what I was really there for. ‘I wondered if there was a letter for me today?’

Mrs Halimeda narrowed her eyes. ‘As I’ve told you every week now for a very long time, if we did it would be delivered to your uncle’s address like everything else is. And before you ask again, yes, we know where you live.’

I felt uncomfortable that I always seemed to annoy her but I wanted to be sure she hadn’t missed anything.

‘I found a door and I think it’s a sign that something’s been sent to me, you see,’ I said.

Mrs Halimeda shook her head and looked over my shoulder as the queue began to grow behind me.

‘What about a postcard?’ I asked.

‘No postcards,’ she said, stern and as unmoved as a stone wall. ‘Next!’

When I moved away I heard her saying ‘Hopeless boy!’ and the lady from the Turkish Baths replying, ‘Well, you only have to look at who raised him.’

It burned inside and made me angry that they’d say something like that about me and Grandfather. But when people had called me names, or when they had looked at me as if I didn’t belong here, Grandfather would say, ‘They don’t know you at all, not like I do.’

And they didn’t know Grandfather like I did either.

When I went outside I found the dog from the cove was sitting beside the door. He put his nose in the air, looking away at first then looking back at me. Maybe his owner was in the post office.

Having no luck, I went back to the cove to check the turtle nest was safe from anybody disturbing it. As I was sitting there, digging away at my own hole in the sand with a stick to see how much work the mother turtle had to do to make her nest, a cool shadow fell across me, blocking the sun. It was the dog again, up on the rocks making shade for me. He climbed down and sat next to me again, looking out to sea.

‘Do you like it here too?’ I said.

He turned his head to look at me. His eyes were warm earth brown.

‘Nobody can bother you here. There’s just the whole wide sea … and us.’

The dog looked away when I didn’t say any more.

I wrapped my arms round my shins, rubbing at the scar on my knee, and rested my chin there as I thought about Grandfather. Would he be coming on a ferry? Or would he have bought himself a new boat?

I remembered once when Grandfather and I had found broken wooden boxes scattered along the tideline of the cove. Then, a few days later, whole crates were washed up, and he said I had to wait and see what else came floating in. After about two weeks and loads of my guesses about what it might be (none of which were right), hundreds of pineapples had been washed up on the beach. The pineapples had come out of the boxes and must have fallen off a ship, but, because the boxes and pineapples were different shapes and weights and sizes, it had taken them different lengths of time to arrive. I’m not saying that Grandfather was a pineapple, and I definitely couldn’t read the sea as well as he could, but it did mean that different things came at different times.

The dog sighed.

‘Be patient, you’ve only been sitting here for one day,’ I said. ‘I’ve been waiting for two years for Grandfather to come home.’

We stayed like that again for a long, longing time.

THE NEXT MORNING, BEFORE Uncle was up, I stuffed some cold chicken and salad in pitta bread for breakfast and went down to the cove. The dog was already there, lying under the propped-up old door. His eyes and eyebrows twitched as he looked up at me but he didn’t lift his head. I sat beside him and picked out the cucumber and tomatoes to eat them first. The dog sat up and was trying really hard not to look at me eating the rest.

‘You must have got up early too so you’re probably hungry,’ I said, giving him a bit of chicken that he swallowed without chewing. It was nice having him beside me, even though he didn’t say or do much; in fact, that was what I liked about him first of all. I liked that he’d sit there quietly with me looking out to sea. It was what Grandfather used to do.

‘Stay there,’ I told the dog. ‘I’m going to get you something else.’

I ran back to Uncle’s restaurant and found the old tin bucket out the back. Then I went to the kitchens and checked on the shelves in the fridge for plates covered in foil with leftovers from the restaurant. I piled food into the bucket, shut the fridge door and then found Uncle standing there.

‘Who’s all that food for?’ he asked.

I wasn’t sure what Uncle would say if he knew I was taking food for a dog. Sometimes there were strays around the restaurant – dogs that people brought on the ferries and left behind, sometimes on purpose, sometimes by mistake. Uncle said the strays put customers off, and the staff knew better than to feed them and chased them away. He probably wouldn’t take kindly to the fact that I was encouraging one of them to hang about.

‘It’s all for me,’ I said. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘Good,’ he said, opening the fridge door to start preparing food. ‘You need feeding up.’

It was a quiet moment without hot voices and burning ovens and the first time I’d had a chance to be with Uncle without him yelling for people to get a move on and take orders, clear tables or hurry up with those chips. This was my opportunity.

Читать дальше