In the early years of the sixteenth century, the town had gone through a brief period of glittering prosperity, home to the court of the young Charles V’s regent, Margaret of Austria. Charles himself, though born in Ghent, spent the first sixteen years of his life in Mechelen, surrounded by artists and philosophers such as the German engraver Albrecht Dürer, the humanist thinker Erasmus of Rotterdam, and Sir Thomas More, future chancellor of King Henry VIII of England. There were also spies, sending back information to their masters in the various courts of Europe about the humanist and occasionally anti-Catholic ideas that were expressed in the town. The composer and copyist Petrus Alamire *worked as a musician at the court and at various times supplied secret reports to Charles’s advisers and to King Henry in England.

Even though Mechelen’s glory was fading by the time Mercator traveled there in the early 1530s, the prosperity that came with such fame remained. Many businesses had been attracted to the town – among them, the burgeoning trade of printing. Mechelen was known as one of the most important centers in the Low Countries for the rapidly developing technology, and that in turn had encouraged geographers and mapmakers, giving it a widespread reputation as a place of geographic study.

Gemma Frisius and his circle were in touch with some of the town’s brightest intellectual flames, among them Frans Smunck, or Franciscus Monachus. If one of them sent Mercator to meet him, it would have been done discreetly, because Franciscus was a marked man; but it seems likely that the young student paid him several visits during his months in Antwerp. Franciscus was one of a religious community known as the Minorite Friars, who believed that by practicing complete self-denial, poverty, and humility, they would lead the world back to pure Christianity. They had been outspoken in their criticism of corruption in the Church for more than two centuries, and at various times, some of their leaders had gone so far as to question the legitimacy of the papacy itself, so that members of the order had been harassed, excommunicated, even burned at the stake. Such a history meant that, at best, the Friars were regarded with suspicion by the Inquisition and the university authorities – but Franciscus had a dangerous reputation of his own as well.

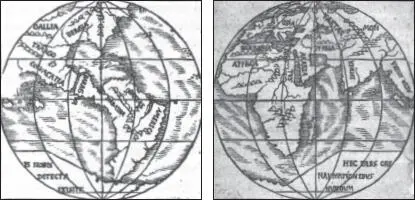

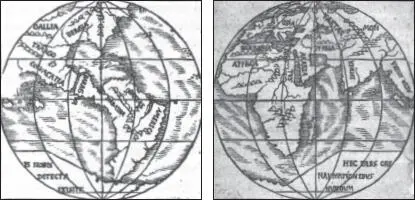

A few years before, he had constructed the first globe to be seen in the Low Countries, along with a short book and a world map. The globe has been lost, but his map shows that he was one of the most advanced geographic thinkers of his day. When it was produced in 1526, the American continents had gradually taken shape after Magellan’s voyage around the southern tip, and Franciscus had done his best to incorporate the latest discoveries of the expeditions that had been pushing northward up its western coastline. North America floundered in a blur of guesswork, depicted as an outgrowth of Asia, and a narrow channel was shown cutting the isthmus to South America, almost foreshadowing the Panama Canal 375 years later. Petrus Apianus had shown such a channel in his world map of 1520, but he had achieved nothing like the accuracy of Franciscus Monachus’s depiction of South America.

Franciscus Monachus’s worldview

British Library, London, Rare Books and Maps Collections

Franciscus’s thoughts ran in more perilous channels as well. By the time Mercator met him he was in his midforties and was known as a critic of the Aristotelian ideas that were at the center of religious orthodoxy, a believer in the importance of observation and measurement, and a man who challenged accepted wisdom. The message of his map had been that exploration, pushing westward to the Indies, was a profitable enterprise, while in his book he had derided “the rubbish of Ptolemy,” and by implication denied the truth of Aristotle’s view of a five-zoned world.

The jumble of fact, rumor, report, and conjecture that surrounded the emerging Americas, let alone Franciscus’s contemptuous view of the great Ptolemy, might have been meat enough for discussion between the two men, but their meetings seem to have ranged over the whole story of the Creation and the history of the world. These were more controversial studies by far than consideration of the coastline of the Americas.

For obvious reasons, Mercator never spoke about his time at Mechelen. How often he traveled there, when or even whether he saw Franciscus, how long he stayed if they did meet, who else might have been with them, were all secrets he took to his grave. Despite the dangers involved, the two men did write to each other, though their letters have been lost. Events a decade later suggest that the religious authorities, at least, believed that their contents would have been enough to damn Mercator as a heretic.

IN ANTWERP, days stretched into weeks, and weeks into months, and still Mercator stayed away from the university. He seems to have been deep in study, agonizing over the conflicts between the world he saw and the world Aristotle described, between reason and the Bible, no doubt debating whether he could return to an institution that stifled original thought as Leuven did. The pleas of the doctors and professors, instructing him to return, were all ignored. It is a mark of how much he was valued as a scholar that when he did eventually go back, they swallowed their pride and readmitted him into the university. 1

The practicalities of making a living from his knowledge soon took hold. Even with the support of the University of Leuven, a delight in nature and in the order and proportion of Creation would never put bread on his table. Philosophy, as his friend and first biographer Walter Ghim put it, “would not enable him to support a family in the years to come.” 2By contrast, geography – globes and maps, like those he had probably seen in Franciscus’s cell among the Minorite Friars – was of continuing interest to wealthy sponsors. Mercator’s religious anxieties, his fascination with new ideas, his interest in the developing picture of the world were all genuine enough, but his later business career showed that he had a shrewd idea of where his own material interests lay – and it was not with the study of philosophy.

Mercator had been granted a license by the university to teach his own classes to young students, but private tuition was never more than a temporary way to support oneself. Through Gemma Frisius, he began to establish contacts and friendships of his own, developing his acquaintance with the young Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, who was clearly a valuable patron for the future. Mercator needed little instruction in how to make himself agreeable to such an influential figure. “Your Grace,” “Your Reverence,” and “most reverend master” are among the phrases with which his correspondence with the young bishop of Arras was larded. Throughout his career, the effusive dedications of maps, globes, and books to powerful sponsors like Granvelle and his father would bear witness to Mercator’s passion for developing a network of influential friends. Such contacts were invaluable to a talented and ambitious man with a career to find and no wealth on which to establish it.

Gemma, with the help of a local goldsmith, Gaspard van der Heyden, had established a workshop in Leuven several years before, to design and make scientific instruments and globes, and in the early 1530s he invited Mercator to join them. Such an invitation was immensely flattering, a mark of considerable respect from someone whose good opinion was valuable, and Mercator had no hesitation in accepting it.

Читать дальше