In fact, she was a good worker, picking things up the first time she was told, and thinking for herself if need be. ‘I’d be delighted,’ I said.

‘I think she might be interested in working with horses when she leaves school, and we want to encourage her in her ambitions.’

‘She should stay here for a couple of weeks and get a taste of the early starts before she makes up her mind about working with horses,’ I quipped, and before I knew it, it had been agreed that Lucy would move in with us for two weeks over the summer. She’d got under my skin and I wanted to help her out if I could.

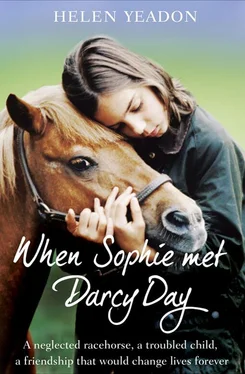

For two weeks Lucy slept in our spare room, ate her meals with us, and I didn’t for one moment regret the decision. She used to get up with me at 5am to boil the huge vats of barley on our Aga for horse feed. She’d help feed the other animals as well, then wash out the feed buckets, muck out the barns, and keep everything neat and tidy around the yard. She became adept at slipping a head collar on the horses and talking quietly to them when they needed to stand still, for example if the farrier was there to trim their hooves. All in all, she was a great asset to me – but still the other children didn’t warm to her.

While Lucy was there, we had a visit one day from a racehorse owner driving a Mercedes, who’d come to check us out and decide if we were the best home for one of his retired horses. I think the stables were a lot more dilapidated than he was used to, but when he saw the condition of our animals, he agreed that his horse, Freddy, could come to us. He duly arrived the next day in a smart trailer. Freddy was a smallish bay with a white blaze down his nose and he was in peak condition, having only come out of training a few weeks before. He danced about as he was unloaded, putting flight to the hens and some geese.

Freddy had had an ignominious end to his ten-year racing career, going from being the winner of Group 1 races at the age of two to trailing at the back of the field more recently. It would take a degree of expertise to retrain him for another career, but I thought we had a good chance of managing it. I stood him in a stable for a day or so to get used to us, then Lucy was with me when I led him up to the field at the end of the lane where we kept our other geldings. Freddy was as naughty as a two-year-old colt, rearing up on his hind legs as I led him, and I thought, ‘Uh-oh, we’re going to have our work cut out.’ He was obviously a highly strung creature.

As soon as I released him into the field, he galloped straight up to the other horses and tried to push his way into the middle of the herd. He obviously didn’t know that there was a pecking order in a herd and new members have to approach slowly and show respect. One horse nosed him roughly out of the way, then another did the same.

‘What are they doing?’ Lucy cried, and I realised she had tears in her eyes. ‘They’re going to hurt him.’

‘No, they won’t,’ I said, watching carefully just in case I was wrong. Freddy approached the group again, but they wouldn’t let him near, rejecting his advances until eventually, head down, he wandered off to graze on his own in a corner.

‘Why won’t they be friends with him?’ Lucy asked, her voice cracking.

Suddenly I realised this was touching a raw nerve for her and I chose my words carefully. ‘Freddy’s been used to being on his own a lot, or with his trainer and jockey, and he’s forgotten how to get on with other horses. He has to earn his place in the herd and wait for them to invite him in instead of charging full pelt into the middle and demanding attention. But don’t worry. It will work itself out eventually.’

‘He must be really upset about it.’

‘Yes, he probably is. But it will be all right in the end.’ At least I hoped it would.

We had to supplement Freddy’s diet while he adjusted to grazing, having previously been fed on concentrates. It became Lucy’s job to go up to the field twice a day and feed him from a bucket, trying to keep it hidden from the rest of the herd so they didn’t think he was getting special treatment, which would have made things much harder. As Lucy fed him, she would stroke his nose and whisper to him, and it was obvious that this lonely girl felt a great affinity for the lonely horse.

From time to time, if another horse was standing separately from the rest of the herd, Freddy would try another approach, sauntering up hopefully, but he was usually met with a hostile kick or a push. He’d panic then canter away again to his solitary grazing. After a few days of this, he started to get nervous when other horses came near and I was concerned that the situation wasn’t resolving itself as quickly as I’d hoped. Fear is always alienating. If a child is scared of dogs and starts behaving oddly around them, even the friendliest breeds of dog will respond by barking or jumping up and will scare the child even more. However, if a child can stay calm, the dogs will be calm too, and it’s the same with horses. Freddy would have to learn to calm down, and this would take time.

‘Why don’t they understand that he only wants to make friends?’ Lucy asked me over and over again.

‘He’s already got a friend,’ I told her. ‘Have you noticed how much he brightens up when you come along?’ It was true. Freddy always rushed over as soon as he saw Lucy approaching the field, whether she was carrying a feed bucket or not. One day, I saw the two of them lying on the grass beside each other, with Lucy chatting quietly and Freddy still and listening. I would have loved to have eavesdropped but if they’d noticed me, it would have spoiled the moment.

‘Freddy was lying down in the field today,’ Lucy told me later, and I knew that was a good sign, because it meant he was settling and wasn’t so scared of the others.

Not long after that, there were a few telltale signs that Freddy was being accepted by the herd. It started with some sniffing of noses, and then a little grooming of necks. Freddy let the others make the approach without either running away or responding with too much eagerness, and in return it seemed they were beginning to accept him.

Around this time, I watched Lucy trying to catch Flirty Gertie one morning, trying hard not to laugh as she kept slipping out of reach. Finally I stepped in to help. I talked to Gertie quietly, approaching very gradually then stooping down using slow, careful movements, and she let me pick her up.

‘Do you see how I did that?’ I asked. ‘You can’t force your presence on a hen, especially not one like Gertie. You need to gain her trust first of all.’

‘OK,’ Lucy nodded, and over the next few days I watched her get the hang of it. She was getting on better with the dogs as well, and one lunchtime I eavesdropped while Sandy was telling her about a new CD she’d bought and Lucy didn’t interrupt once to boast that she had better CDs at home. She was learning.

I’d like to say Lucy became friends with the other children at Greatwood that summer, but nothing happens that quickly after a bad first impression has been formed. However, she made a firm friend of Freddy. After the two weeks she stayed with us, Lucy kept popping back to see Freddy whenever she could, and as soon as he spotted her coming down the lane, Freddy would rush up to the fence to greet her. There was a meeting of kindred spirits there that I think helped both of them through a difficult time.

The summer holidays ended and Lucy went back to school, so she could only visit us at weekends. Her father phoned us one evening, though.

‘I can’t thank you enough for what you did for Lucy over the summer,’ he said. ‘She seems much more settled at school and has made some new friends, so we’re very grateful.’

Читать дальше

![Джулиан Ассанж - Google не то, чем кажется [отрывок из книги «When Google Met WikiLeaks»]](/books/405461/dzhulian-assanzh-google-ne-to-chem-kazhetsya-otryvok-thumb.webp)