One interesting subject which the author, in her modesty, has not sufficiently emphasized is the very considerable part she played in the practical work of the expeditions. She mentions in passing her struggles to produce photographs without a darkroom and her labelling of finds, but that is not enough. When, later, I was fortunate enough to spend a week with the Mallowans at Nimrud, near Mosul, I was surprised how much she did in addition to securing domestic order and good food. At the beginning of each season she would retire to her own little room to write, but as soon as the pressure of work on the dig had mounted she shut the door on her profession and devoted herself to antiquity. She rose early to go the rounds with Max, catalogued and labelled, and on this occasion busied herself with the preliminary cleaning of the exquisite ivories which were coming from Fort Shalmaneser. I have a vivid picture of her confronting one of these carvings, with her dusting brush poised and head tilted, smiling quizzically at the results of her handiwork.

This remembered moment adds to my conviction that although she gave so much time to it, Agatha Christie remained inwardly detached from archaeology. She relished the archaeological life in remote country and made good use of its experiences in her own work. She had a sound knowledge of the subject, yet remained outside it, a happily amused onlooker.

That Agatha could find intense enjoyment from the wild Mesopotamian countryside and its peoples emerges from many of the pages of Come, Tell Me How You Live . There is, for one instance, her account of the picnic when she and Max sat among flowers on the lip of a little volcano. ‘The utter peace is wonderful. A great wave of happiness surges over me, and I realize how much I love this country, and how complete and satisfying this life is…’ So, in her short Epilogue looking back across the war years to recall the best memories of the Habur she declares: ‘Writing this simple record has not been a task, but a labour of love.’ This is evidently true, for some radiance lights all those everyday doings however painful or absurd. It is a quality which explains why, as I said at the beginning, this book is a pure pleasure to read.

JACQUETTA HAWKES

1983

A-SITTING ON A TELL

( With apologies to Lewis Carroll )

I’ll tell you everything I can

If you will listen well:

I met an erudite young man

A-sitting on a Tell.

‘Who are you, sir?’ to him I said,

‘For what is it you look?’

His answer trickled through my head

Like bloodstains in a book.

He said: ‘I look for aged pots

Of prehistoric days,

And then I measure them in lots

And lots of different ways.

And then (like you) I start to write,

My words are twice as long

As yours, and far more erudite.

They prove my colleagues wrong!’

But I was thinking of a plan

To kill a millionaire

And hide the body in a van

Or some large Frigidaire.

So, having no reply to give,

And feeling rather shy,

I cried: ‘Come, tell me how you live!

And when, and where, and why?’

His accents mild were full of wit:

‘Five thousand years ago

Is really, when I think of it,

The choicest Age I know.

And once you learn to scorn A.D.

And you have got the knack,

Then you could come and dig with me

And never wander back.’

But I was thinking how to thrust

Some arsenic into tea,

And could not all at once adjust

My mind so far B.C.

I looked at him and softly sighed,

His face was pleasant too…

‘Come, tell me how you live?’ I cried,

‘And what it is you do?’

He said: ‘I hunt for objects made

By men where’er they roam,

I photograph and catalogue

And pack and send them home.

These things we do not sell for gold

(Nor yet, indeed, for copper!),

But place them on Museum shelves

As only right and proper.

‘I sometimes dig up amulets

And figurines most lewd,

For in those prehistoric days

They were extremely rude!

And that’s the way we take our fun,

’Tis not the way of wealth.

But archaeologists live long

And have the rudest health.’

I heard him then, for I had just

Completed a design

To keep a body free from dust

By boiling it in brine.

I thanked him much for telling me

With so much erudition,

And said that I would go with him

Upon an Expedition…

And now, if e’er by chance I dip

My fingers into acid,

Or smash some pottery (with slip!)

Because I am not placid,

Or if I see a river flow

And hear a far-off yell,

I sigh, for it reminds me so

Of that young man I learned to know—

Whose look was mild, whose speech was slow,

Whose thoughts were in the long ago,

Whose pockets sagged with potsherds so,

Who lectured learnedly and low,

Who used long words I didn’t know,

Whose eyes, with fervour all a-glow,

Upon the ground looked to and fro,

Who sought conclusively to show

That there were things I ought to know

And that with him I ought to go

And dig upon a Tell!

This book is an answer. It is the answer to a question that is asked me very often.

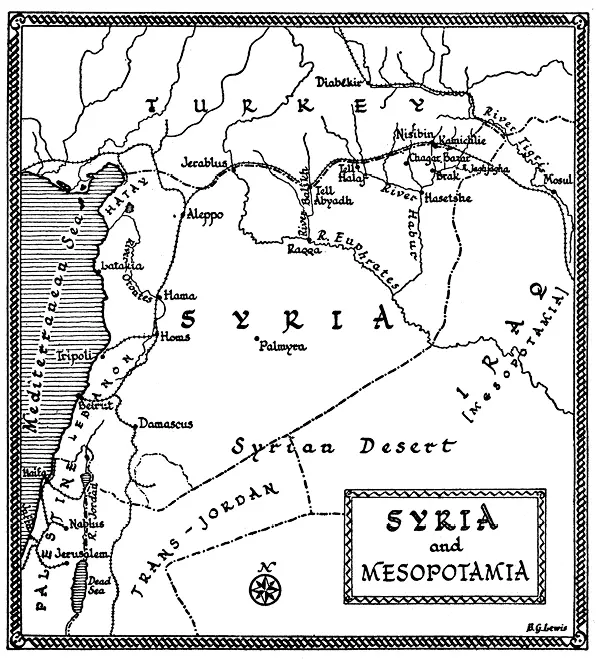

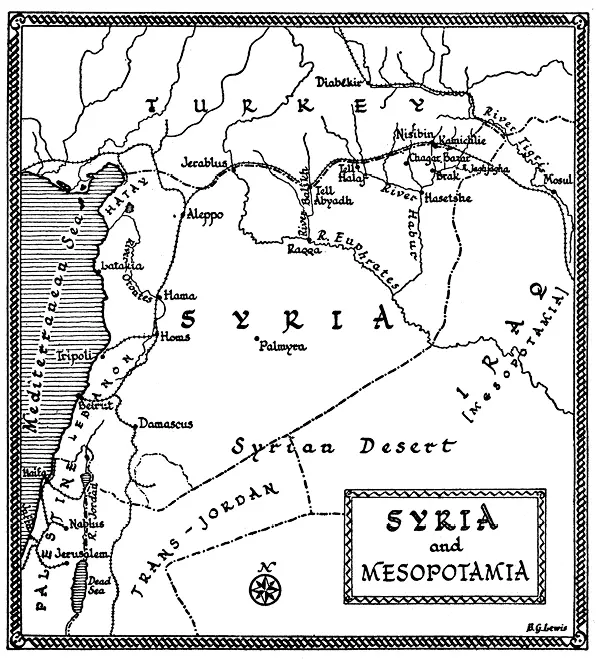

‘So you dig in Syria, do you? Do tell me all about it. How do you live? In a tent?’ etc., etc.

Most people, probably, do not want to know. It is just the small change of conversation. But there are, now and then, one or two people who are really interested.

It is the question, too, that Archaeology asks of the Past— Come, tell me how you lived ?

And with picks and spades and baskets we find the answer.

‘These were our cooking pots.’ ‘In this big silo we kept our grain.’ ‘With these bone needles we sewed our clothes.’ ‘These were our houses, this our bathroom, here our system of sanitation!’ ‘Here, in this pot, are the gold earrings of my daughter’s dowry.’ ‘Here, in this little jar, is my make-up.’ ‘All these cook-pots are of a very common type. You’ll find them by the hundred. We get them from the Potter at the corner. Woolworth’s, did you say? Is that what you call him in your time?’

Occasionally there is a Royal Palace, sometimes a Temple, much more rarely a Royal burial. These things are spectacular. They appear in newspapers in headlines, are lectured about, shown on screens, everybody hears of them! Yet I think to one engaged in digging, the real interest is in the everyday life—the life of the potter, the farmer, the tool-maker, the expert cutter of animal seals and amulets—in fact, the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker .

A final warning, so that there will be no disappointment. This is not a profound book—it will give you no interesting sidelights on archaeology, there will be no beautiful descriptions of scenery, no treating of economic problems, no racial reflections, no history.

It is, in fact, small beer—a very little book, full of everyday doings and happenings.

AGATHA CHRISTIE MALLOWAN

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Читать дальше