Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

© Zoe Patterson and Jane Smith 2018

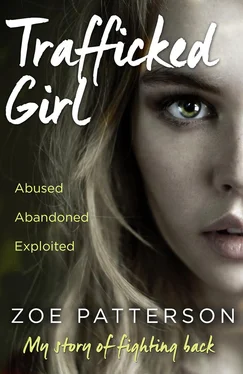

Cover layout design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2018

Cover photograph (posed by a model) © Alexander Vinogradov/Trevillion

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Zoe Patterson and Jane Smith assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008148041

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008157586

Version: 2018-01-30

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Definition

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

About the Authors

About the Publisher

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Care: (1) the provision of what is necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance, and protection of someone or something; (2) serious attention or consideration applied to doing something correctly or to avoid damage or risk.

For many years, I believed that what happened to me when I was a little girl was my fault. I suppose if you tell someone almost anything over and over again from a very young age, they’ll grow up with it hardwired into their brain as a ‘fact’. Later, when they’re old enough to think for themselves, and if the fact has an objective or scientific basis, they might be able to disprove it. But that isn’t so easy to do if it’s something more subjective, particularly if it subsequently seems to be confirmed by other people and by apparently unconnected events.

The ‘fact’ I was told by my mother throughout my childhood and into adulthood was that I was to blame for all the horrible things that were done to me – many of which she actually did herself. So I was glad, although very scared, when the day came that I was taken into care. Maybe now, I thought, the bad stuff will stop happening, and then one day I’ll be able to live the sort of life I’ve always wanted to live – the sort of life my mum always said I didn’t deserve.

As things turned out, however, I was one of the unlucky ones for whom the care part of ‘being taken into care’ didn’t match any dictionary definition. In fact, what happened to me while I was living at Denver House was even worse than anything that had happened to me at home. Which made me think that maybe Mum had been right all along and I really was living the life I deserved.

I had just woken up and was crossing the narrow landing at the top of the stairs when Mum came out of her bedroom. For some children, home is the only place they feel safe. For others, it’s the one place they know they aren’t. So when Mum took a step towards me, I felt the muscles in my body tense as I instinctively leaned away from her.

I was four years old, and I’d known since I was old enough to understand anything that I didn’t have to have done something wrong – or, at least, nothing I was aware of – for my mum to be angry with me. On this particular morning, however, instead of shouting at me and slapping me or pulling my hair, she just stood in the doorway of her bedroom and smiled.

It wasn’t a nice smile, the way I’d seen other mums smile at their kids when they came to pick them up from school. It was more like a nasty sneer, as if she knew something bad that I didn’t know and was relishing the prospect of telling me what it was. She didn’t say anything though, as I hovered on the landing, trying to decide whether my own anxious, tentative smile would annoy or appease her. She waited for me to take two hesitant steps down the stairs and then she pushed me.

‘Oh dear, grab the handrail,’ Mum called. But the concern in her voice was exaggerated and insincere, and she laughed out loud when I stumbled and fell, smacking my head into the wall at the bottom of the stairs.

I was still lying on the worn carpet in the hallway, shocked and disorientated, when Dad ran out of the living room and crouched down beside me.

‘Jesus Christ, Maggie,’ he shouted at Mum, who was standing smirking halfway down the stairs. ‘What happened? And what’s so funny? She’s hurt herself.’

‘Well, don’t blame me .’ Mum put her hands on her hips and glared angrily at us both. ‘It’s not my fault she’s clumsy and stupid. She tripped.’

For a moment I was forgotten as they shouted and swore at each other. So I sat up, touched the painful bump on the side of my head very gently with my fingertips, then examined the red mark on my elbow that I knew would soon develop into a bruise. It felt as though someone was pounding on the inside of my skull with something very heavy, and as the sound of my parents’ angry voices filled the air above me, I could feel tears stinging my eyes. But I was determined not to cry.

‘What happened, Zo?’ Dad put his hands under my arms and lifted me to my feet.

‘I told you, she tripped. Didn’t you?’ Mum was smiling the nasty smile again, although less broadly this time, maybe because she didn’t want Dad to see it as he guided me into the living room, where he sat me down in her chair saying, ‘I’ll get you some juice. That’ll make you feel better.’

It was rare for anyone to be kind to me at home, and although the memory of it makes me sad when I think about it today, I was too scared at the time to appreciate Dad’s concern for me, because I knew that as soon as he’d gone to work, Mum would find a way of making me pay for his attention.

I think Dad knew about some of the things she did to me, which was why he sometimes got angry with her, like he did that day. He certainly wasn’t aware of all of them though, as she was careful to hide her treatment of me, particularly when I was very young, and I didn’t ever say anything because I knew that if I did, my parents would shout and maybe fight with each other for a while, then Dad would go out and I’d be left alone with Mum.

So that time when she pushed me down the stairs is one of only very few occasions I can remember when Dad stood up for me. And although he did sometimes say nice things to me when I was a little girl, Mum always seemed to be standing behind him whenever he did, looking at me over his shoulder with a spiteful expression on her face that said quite clearly, ‘Just you wait until he’s gone to work.’

Читать дальше