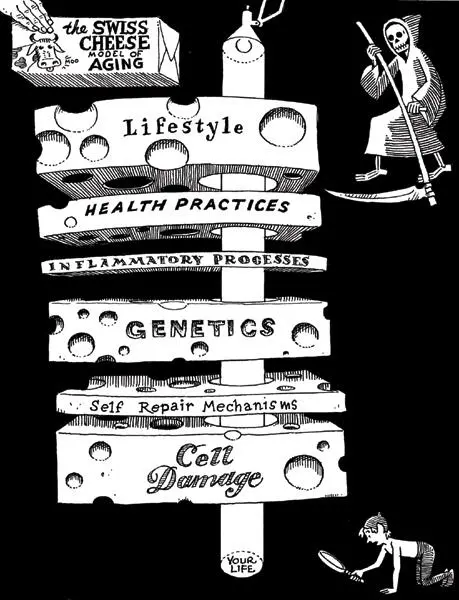

4. Ageing Is Not About Individual Problems but Compounded Ones

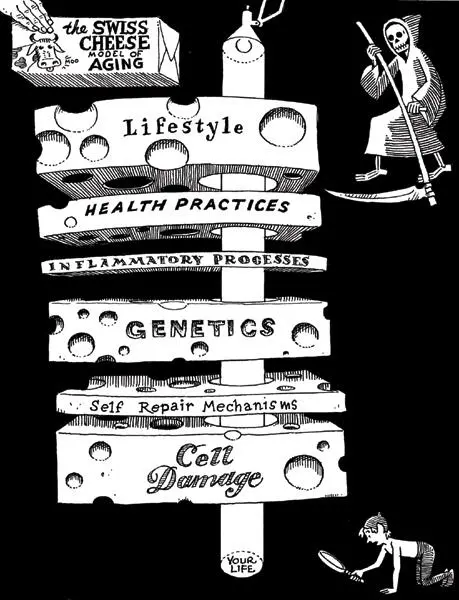

Spend any time at a deli counter, and you know that Swiss cheese has two different looks. Big holes or small holes, all in random order and patterns. A good way to think about ageing is to imagine yourself looking through a dozen slices of stacked-up Swiss cheese (see Figure Intro 2). If the holes are small and the slices are thick, you can’t see through the stack. Now pretend that each of these Swiss cheese slices represents a layer of protection that your body provides to prevent ageing. People who are vibrant and strong may have small holes in their system – stuff that lets through a few problems, but nothing too major. Maybe they’ve got a little hole in their slice of heart health, and a few little holes in their slice of brain health, and a medium-sized hole in their slice of chromosome health. Nothing major lets you see through the stack.

FACTOID

Currently, there are more than six thousand centenarians in the UK. This number is expected to increase to forty thousand in 30 years’ time. (The Guardian , 18 January 2006)

As ageing takes effect, however, those holes can get a little bigger, or the cheese can get a little thinner. When big holes from one slice perfectly align with big holes from another slice, then, in effect, you’ve got big problems. That’s a little bit what ageing is like: the small problems may not have a big effect here and there, but when they grow, and when they interact with other problems, then you’ve created what we like to call a ( cue scary orchestra music ) web of causality. That’s when seemingly small health problems spiral into bigger ones – all possibly triggered by several different causes.

Figure Intro 2 Cheese Doodle Each layer of resilience we have against ageing is like a slice of cheese. The differences in hole size, number of holes and thickness of slices describe how we protect ourselves against ageing.

5. Ageing Is Reversible – All You Need Is a Nudge

Most people think ageing is a landslide of a process, that we’re destined to use walkers and hearing aids and thick glasses no matter what. And while we’re not saying that you will absolutely avoid all the bumps (big and small) along the way, we are saying that ageing isn’t as inevitable as a morning trip to the toilet.

What you will learn in this book is how to nudge your systems so that they work in your favour to create leverage points in life. And the great thing is that it’s never too early or too late to start making these changes. You don’t need a complete overhaul, because, frankly, your body is a pretty fine piece of machinery. What you’ll ultimately do is find and fix your own personal weak links – the things that make you most vulnerable to the effects of ageing. The cumulative effect of those nudges, though not major from a behavioural or even a biological perspective, can be huge when it comes to increasing the length and quality of your life.

The truth about ageing is that you – right now – have the ability to live 35 percent longer than expected (today’s life expectancy is seventy-five for men and eighty for women) with a greater quality of life and without frailty. That means it’s reasonable to say that you can get to one hundred or beyond and enjoy a good quality of life along the way. While relying on the talents, skills and knowledge of others may get you out of a medical jam, what you really want is to avoid it in the first place. Restricting calories, increasing your strength and getting quality sleep are three of nature’s best anti-ageing medicines. Together, these activities – as well as the other actions we recommend – control 70 percent of how well you age. Wouldn’t you want to hold the power of your future in your hands, rather than put it in someone else’s?

Just because you’ve made mistakes in the past doesn’t mean you can’t reverse them. Even if you’ve had burgers for breakfast or fried your brain cells with stress, you’re not necessarily destined to wear elasticated waistbands and forget birthdays. No matter what kind of life you’ve already led, ageing is reversible: you can have a do-over if you want it. If you perform a good habit for three years, the effect on your body is as if you’ve done it your entire life. Even better, within three months of changing a behaviour, you can start to measure a difference in your life expectancy.

As we said, ageing is inevitable, but the rate of ageing is not. Consider this fact: only 10 percent of people are classified as frail when they’re in their seventies. By the time people reach one hundred, almost 100 percent are considered frail. What we’re trying to do is make sure that percentage stays lower for longer. We want you to feel as good at the end of the race as you do at the start.

Our goal here is to ensure that you have a high quality of life until whatever time – forgive our bluntness – you drop dead. That’s the ideal scenario, right? Nobody wants to spend their golden years on diets of jelly, suffering from bedsores, or not remembering the previous nine decades. You want to feel like you’re thirty even when you’re eighty. You want to have the wisdom of a grandparent without feeling like one. So our goal isn’t to get you to 120 – unless those 120 years come with quality.

After all, living longer shouldn’t be about “taking longer to die”, which is what so many people think it means. It should be about enjoying every moment of a longer life – and taking longer to live.

You want to live long and live well. You want to feel alive while you’re living.

You don’t want to grow old. You want to stay young.

This is the way.

Now get on with it.

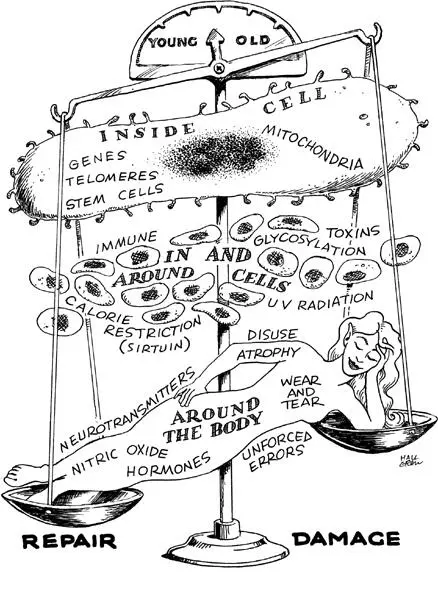

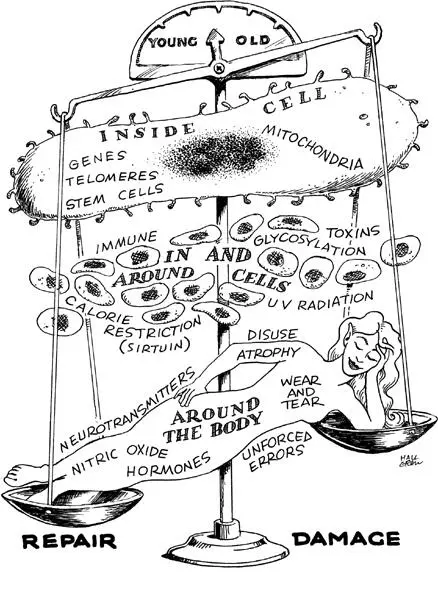

Figure Intro 3 Major Ager Crib Sheet The scale of ageing balances between repair and damage mechanisms, and we have seven Major Agers in each category weighing in on whether you are growing younger or older. The higher up the Major Ager is listed on our scales, the more it acts within our cells.

Major Ager Bad Genes & Short TelomeresHow Genetics Influences Ageing – and You Control Your Genes

As we get older, it’s easier and easier to pass the blame for our own health problems on to other people. Recently diagnosed with high cholesterol? Aha, three grandparents and two great-uncles all died of heart disease. Accidentally put the ketchup in the freezer the other day? Oh yes, Aunt Matilda had a touch of dementia. Battling a weight problem for most of your life? Yup, Dad and his brothers believed in the three food groups of cheese ravioli, meat sauce, and multiple helpings.

In fact, many of us buy into a very similar theory of ageing: we’re born with our health destiny. That is, our genes – the chromosomal alphabet soup that includes ingredients from our parents, their parents and so on – are primarily responsible for determining whether we’ll get heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s or any of the other diseases or conditions that can turn a grade-A quality of life to spoiled minced beef.

But that’s simply not the way ageing works. Your genes are important, especially when it comes to one of the most powerful age-related problems: memory loss. Your genetic destiny, however, is not inevitable.

What do we mean by that? Think back to the city that we outlined for you in the introduction, and consider your genes as the physical location of that city. Some characteristics you simply can’t change. Chicago is windy, Manchester is rainy, San Francisco is built on fault lines, Cape Hatteras is in the path of tropical storms. A city’s location serves the same function as your body’s genes. Your genetic traits make you more or less predisposed to health-related windstorms, snowstorms, earthquakes and hurricanes. But just as you can modify cities to adjust to natural geography and natural occurrences, you can also protect yourself from abnormalities in your genes if you’re unhappy with how you’ve been genetically programmed.

Читать дальше