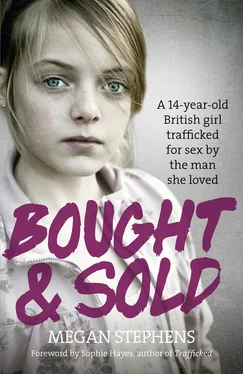

I hope that when you’ve read my story, you’ll understand why I won’t ever identify the man I’ve called Jak, why I’ve changed the names of everyone in it and why I’m so afraid of the fear coming back.

My lack of courage makes me feel very guilty, not least because I know that there are other girls who’ve been forced into prostitution by the same human traffickers who tricked and controlled me. I don’t have to try to imagine how miserable and frightened those girls are. I know how they feel as they fall asleep every night wishing the morning won’t come so that they won’t have to live through another day of violence, humiliation and aching loneliness. I felt that way myself almost every day for six years. Now, five years later, I still have nightmares, and I still sometimes forget how not to be afraid.

What happened to me in Greece stripped away the last remnants of my self-esteem. And when you think you’re worthless, it’s difficult to believe that anyone could love you. But I know my mum loves me and before I tell my story I just want to say that I love her too.

Perhaps things would have turned out differently if Mum had insisted on intervening more forcefully when I made my first really bad decision in Greece. The problem was that she didn’t have any more idea than I did that there are actually people in the world who buy and sell human beings. So she believed me when I told her I was happy. She put the photographs I sent her up on the wall in the bar where she works, and she didn’t suspect for a single moment that I was lying to her.

There are lots of incidents in my story that will make you wonder how anyone could be as stupid as I was. It’s something I still don’t really understand myself, except that I was very young and naïve when I fell in love with Jak. Perhaps that was at least part of the reason why I suspended what little commonsense I had and simply accepted everything he told me. And if I didn’t realise what was happening, I certainly can’t blame my mum for not realising it either.

Something else I didn’t know until recently is that there are estimated to be more than 20 million victims of forced labour – including victims of human trafficking for labour and sexual exploitation – throughout the world. That means that there are more than 20 million men, women and children whose lives have been stolen, who’ve been separated from their families and friends, and who are being forced to work incredibly long hours, often in appalling conditions. A significant number of those people will have been tricked, as I was, by someone they believed loved them or by the promise of legitimate work. I wouldn’t for one moment blame any of them for what’s happened to them. So I know I shouldn’t blame myself, entirely, for what happened to me, although I still find it difficult not to.

I realise that by telling my story I’m exposing myself to the judgement of other people, some of whom won’t be as understanding as I might hope. But if reading it makes just one person think twice before trusting someone they shouldn’t trust, and as a consequence they don’t take a step they’ll regret for the rest of their lives, I’ll feel that something positive has come out of it all.

I was 14 when I went to Greece with my mum. At first, that seemed to be the obvious place to start my story. But when I really began to think about it, I realised it started much earlier than that, when I was just a little girl. Revisiting my childhood has helped me to understand why I later acted and reacted in some of the ways I did.

I was almost 12 years old when I began to develop from ‘child with problems’ into ‘problem child’. Even at that young age, I already had a tightly coiled ball of anger inside me that sometimes erupted into bad behaviour. I wasn’t ever violent; I was just argumentative and determined to do whatever daft, ill-advised thing I had set my mind on. Although I’ve always loved them both fiercely, I used to argue endlessly with my sister, and I would backchat my mum too, in the loudly defiant way some teenagers do. Then, at almost 12, I started wagging school and running away from home.

I feel sorry for Mum when I think about it now. It must have all been rather a shock for her, particularly as I had been quite a well-behaved, academically able little girl before then. I know she found it really difficult to deal with the new me, at a time when she had enough problems of her own.

I was four when my mum and dad split up. My earliest bad memory is of the day Dad left. I was sitting at the top of the stairs in our house, sobbing. I used to remember that day and think I was crying because I had a terrible stomach ache, until I realised that I get terrible stomach aches whenever I’m frightened or upset. So I think the tears – and the stomach ache – were because Dad was leaving.

When he came out of the living room into the hallway, I called down to him, ‘Please, Dad, don’t go.’ When he stopped and looked up at me, I held my breath for a moment because I thought he might not be going to leave after all. But then he waved and walked out of the front door.

I adored my dad and in some ways I never get over his leaving. But I’ve got lots of good memories of my stepdad, John, who came to live with us not long after Dad left. I used to love school when I was young and one of the things I really liked about John was the way he always talked to me about whatever it was I was learning and then helped me with my homework. He was tidy too, unlike Dad, and the house was always clean and nice to live in when he was there.

We lived in a good area of town at that time. Mum had made sure of that. She said she wanted my sister and me to have more opportunities and a better life than she had had, which is also why she insisted on us always speaking and behaving ‘properly’.

Dad had not moved very far away when he left – just to the other side of town – and some weekends my sister and I would go to stay with him. Mum told me later that he had started drinking and taking drugs before they split up. I didn’t know about the drugs as a child, but I think I was aware that he drank, or, at least, I was aware of the consequences of his drinking, because of the sometimes scary way he behaved when he was drunk.

Whenever my sister and I went to stay with him, Mum would give him money so that he could look after us. But he must have spent it on alcohol, because we would go home on Sunday nights with tangled hair and dirty clothes, feeling ravenously hungry. It didn’t make any difference to the way I felt about Dad though: I still adored him, and I would scream and cry every time we had to leave him.

I don’t know if he was trying to fight his addictions or if he was happy with his life the way it was. Perhaps drugs and alcohol were all that really mattered to him. It certainly sometimes seemed that way, and that when he’d had to choose between his addictions and his wife and children, we had been the ones he had abandoned. He even gave up seeing my sister and me at weekends in the end, when he became so weird and unpredictable that Mum had to stop us going there.

I missed Dad a lot for a while, and then a couple of friends of Mum’s and John’s started coming over at the weekends with their two children and I began not to mind so much about not going to visit him. Every Saturday evening, Mum would make a huge bowl of popcorn for us kids to eat while we watched a film. Then we would go up to bed and the adults would turn on the music. I loved those weekends.

I did still miss my dad, but staying with him had started to get a bit frightening and, to be honest, I wasn’t sorry not to be going there anymore. There was never anything to eat in his house and when we told him we were hungry, he just got angry and shouted at us, which made me anxious – for myself, for my little sister and for him. So it was nice to spend the weekends just being a kid at home, playing and joking around and not having to worry about anything. Until the fights started.

Читать дальше