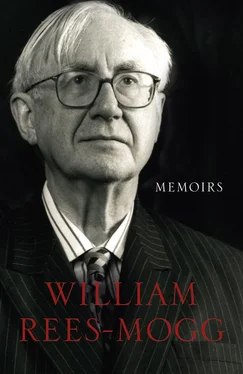

1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...18 I slipped easily into the notion that I was reading the life of a congenial, great man.

Johnson is also a moralist; which is a dangerous thing to be, because it is hard to make moral judgements without becoming something of a prig and a hypocrite. To Boswell, himself constantly in a state of moral torment and doubt, it was the confidence of Johnson’s morality which was most attractive. I do not think that was so in my case; no doubt I have myself been too self-confident in making moral judgements. I felt that Johnson was right to consider moral issues as essential to life. At ten I wanted to learn how to make sound moral judgements, and I wanted to know how to write good English prose. I thought Johnson could help me to learn both those things.

I respected but did not really share Johnson’s Toryism. Decades later, as I was told, Michael Hartwell, then the proprietor of the Daily Telegraph , was discussing with Bill Deedes his possible successor as Editor. I had recently given up the editor-ship of The Times , and my name was mentioned. ‘He’s not our kind of Tory,’ said Michael, and that closed the issue. I never have been a Daily Telegraph Tory, and I did not find myself a Samuel Johnson Tory either. He was a near Jacobite, King and Country, traditional Tory, although he was liberal in his views of the great social issues of race and poverty, and not an imperialist. I have always been a John Locke, Declaration of Independence, Peelite, even Pittite, type of Tory, and Johnson would have sniffed me out as a closet Whig.

It was not only Johnson’s mind and personality which attracted me, but the book itself, and above all the eighteenth century. I do not believe in reincarnation, but that is the best way to describe the impact that Boswell’s Life of Johnson had on me. I felt that I was re-entering a world to which I belonged, a world which was more real to me, and certainly more attractive, than the mid twentieth century. I felt that what had happened since Johnson’s death in 1784 was a prolonged decline of civilization, the industrial revolution, ugly architecture, the slums, the heavy Victorian age, the great European wars of Napoleon, the Kaiser and Hitler. I yearned for the age of harmony before the fall. It took me half a lifetime to get used to the modern age, and I have never become particularly fond of it.

In reading Boswell, I was able to slip into the garden of the eighteenth century and regain a lost paradise. I enjoyed everything about that century, the houses, the furniture, the landscape, the paintings, the music, the literature, the letters, the politics, the people. Although this perception of the eighteenth century as a golden age has gradually eroded, it still remains quite vivid. In the years when our own family was growing up, Gillian and I lived in two fine eighteenth-century houses, Ston Easton Park in Somerset – a beautiful extravagance – and Smith Square in London. Now we live in an early twentieth-century flat in London and a late fifteenth-century house in Somerset. I delight in both of them; the eighteenth-century nostalgia has eased. But it is still the period from 1714, the death of Queen Anne, to 1789, the year of the French Revolution, which is my true homeland in history and literature.

I never suffered from Johnson’s extreme fear of death, but I did feel sympathetic to his congenital melancholy. I also admired the energy he put into friendship. The passage I best remember from my first reading of Boswell’s Life is the one in which he helped a nearly destitute Oliver Goldsmith; this account is in Johnson’s own words:

I received one morning a message from poor Goldsmith, that he was in great distress, and as it was not in his power to come to me, begging that I would come to him as soon as possible. I sent him a guinea, and promised to come to him directly. I accordingly went as soon as I was dressed, and found that his landlady had arrested him for his rent, at which he was in a violent passion. I perceived that he had already changed my guinea, and had got a bottle of Madeira and a glass before him. I put the cork into the bottle, desired he would be calm, and began to talk to him of the means by which he might be extricated. He then told me that he had a novel ready for the press, which he produced to me. I looked into it, and saw its merit, told the landlady I should soon return, and having gone to a bookseller, sold it for sixty pounds. I brought Goldsmith the money, and he discharged his rent, not without rating his landlady in a high tone for having used him so ill.

The novel was The Vicar of Wakefield ; £60 would probably have had the purchasing power of £5000 in modern money.

That summer I was in the senior form of the junior section of the Clifton Preparatory School, a form taught by Captain Read. With war imminent, it was a time of heightened emotional tension, a time when everyone’s imagination was stretched. Read was a quiet man, a good schoolmaster, who was a veteran of the First World War. I now suspect that he may have been one of those good officers who never wholly recovered from their war experience; he did not speak of it to us.

Captain Read set us an essay on ‘a building we had visited during the holidays’. I wrote about the little Catholic church at East Harptree, and described, in rather sentimental terms, how it had been built by poor Irish labourers in the nineteenth century. Captain Read recognized that this was an unusual piece of writing for a ten-year-old boy, gave it a top mark, perhaps even ten out of ten, and praised it to the class as exceptionally well written.

This encouragement was very important to me. Before that I had no idea I had any special talent for writing. I knew that I was reasonably bright by the standard of the school; I usually came third in class placings, behind my contemporaries Pym and Foster, who contended for the top position. Captain Read told me I had a special talent for writing essays, and I believed him. I have been writing them ever since.

It was through my fascination with Johnson that I came to read the poets of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. My favourite book, one of the favourite books of my lifetime, became Johnson’s Lives of the Poets . My mother bought for me a calf-bound set of the 1779 first edition of Johnson’s Poets , with the works of the poets from Cowley to Lyttleton in fifty-six volumes, two volumes of index, and twelve volumes of the Lives . This was a fourteenth-birthday present, bought from George’s of Bristol; it still has their price marked in it, of £6 15s. The first owner had been an eighteenth-century clergyman, Francis Mills, who was born in 1759. He may have bought the first volumes when he was twenty, and lived through to die in 1851 in his ninety-second year. I hope these little books gave him the lifetime’s happiness they have given me.

Johnson’s Poets covers the period from the 1620s to the 1760s. The minor poets of this period include Rochester, the libidinous Earl; Addison, one of the most delightful of English essayists; Gay, who wrote The Beggar’s Opera ; the saintly Isaac Watts, one of the best English hymn writers, and Gray, who wrote the Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard . When I suffered from adolescent depression at Charterhouse, I found Gray’s Elegy , the mirror of my mood, a great comfort.

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea,

The Ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

In Johnson’s collection, there are four major literary voices, those of Milton, Dryden, Swift and Pope; of those Swift is a great satirist rather than a great poet. Dryden is indeed a great poet, free-flowing with fire and energy, but I never found him a particularly interesting writer despite the intellectual quality of his criticism. The two great poets whom I have come back to again and again, who, after Shakespeare, have done most to shape my mind, are Milton and Pope. Milton came rather the earlier of the two; I can remember first hearing Lycidas read in a form room at Clifton.

Читать дальше