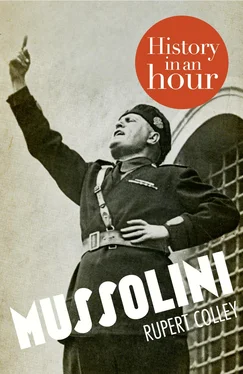

Mussolini and colleagues during the ‘March on Rome’, 28 October 1922.

On 24 October 1922, Mussolini’s fascists broke a strike organized by the socialists. A triumphant Mussolini spoke at a rally in Naples: ‘Either the government will be handed to us or we will seize it for ourselves by marching on Rome.’ The threat of civil war in Italy loomed large and Mussolini and his fascist party decided to stage a coup despite knowing they were no match for the Italian army. Luigi Facta, the prime minister, offered Mussolini a place in his government. As his supporters congregated, Mussolini refused; he had his sights set on higher things.

Facta, panicking, requested that the king declare a state of martial law and to allow him to use the army to squash the fascists now amassing outside the capital. The king initially agreed and then, fearing that such an action would spark a civil war, changed his mind. At a deeper level, the king harboured admiration for Mussolini and he knew large factions within the army’s command felt much the same. Victor Emmanuel, the ‘little sardine’ as Mussolini called him, also feared that if Mussolini took power by force he, as king, might risk being deposed in favour of his cousin, the fascist-supporting Duke of Aosta. Appalled by the king’s decision, Facta resigned.

Twenty thousand fascists began the March on Rome but stopped twenty miles north of the capital where, with the rain pouring down, half of them promptly returned home. Mussolini himself joined the march at various stages to have his photograph taken and be seen marching shoulder-to-shoulder with his men. The photos show Mussolini in typical pose – his jaw jutting, his chest inflated and his steely eyes fixed on his destiny. But there was only so much marching Mussolini wanted to do in the rain and instead he arrived in the capital by express train.

The king believed it was better to have Mussolini within his government than causing unrest from the outside so, as Facta had done, he offered the fascist leader a role in his government. Mussolini refused everything but the top job. The bluff worked, and on 28 October 1922, when the two men met, the king duly offered Mussolini the role of prime minister. Mussolini had achieved power not through revolution, as perhaps the romantic in him would have preferred, but via constitutional means.

The following day the march continued but with victory already won. This was more of a celebratory stroll than a revolutionary march. Elsewhere, the violence continued as jubilant fascists assaulted the beaten socialists.

Aged only 39, the 27th and, until 2014, youngest prime minister in Italian history, Mussolini’s years in power had begun. (He would also become Italy’s longest-serving prime minister.) In a speech delivered in Milan on 6 December 1922, he said, ‘My father was a blacksmith, and I often worked with him. He bent iron; but I have the harder task of bending souls.’

The Matteotti Crisis The Matteotti Crisis Totalitarianism Mussolini and the Pope The Duce’s Cult of Personality Mussolini’s Women Anti-Semitism Mussolini’s Foreign Adventures Mussolini’s Wars Austria, Czechoslovakia and Albania War Mussolini’s Downfall The Rescue of Mussolini The Italian Social Republic Execution of Mussolini The Italian Holocaust Mussolini’s Body Appendix 1: Key People Appendix 2: Timeline Copyright Got Another Hour? About the Publisher

Mussolini may have been ready to bend souls but despite being prime minister, and foreign minister, he was still far from obtaining absolute power. He headed a government in which his party was still very much a minority and at the mercy of the governing coalition. He was forced to work within the confines, as he saw it, of democracy. Thus Mussolini now took steps towards his ultimate goal – dictatorship. Two months after the March on Rome, he formed the Fascist Grand Council, ostensibly to act as a conduit between his party and the Chamber of Deputies. The Grand Council had the power to dispose of its head but only Mussolini had the power to convene meetings and set its agenda, making such power essentially theoretical. Filled with his supporters, it was, in practice, merely a mouthpiece for Mussolini and a means of diminishing parliament’s voice. Meanwhile, his blackshirts continued to police the streets, suppressing opposition and silencing dissent by means of violence and coercion.

In 1923, the Grand Council passed the Acerbo Law, named after its author Giacomo Acerbo. The law rigged the electoral system in such a way that come the next elections, Mussolini would gain a sizeable majority. The socialists tried to block the Act becoming law but were left in a minority.

Come the national elections five months later, on 6 April 1924, Mussolini’s rightist coalition, unsurprisingly, won convincingly, gaining 374 of the 535 seats (almost 70 per cent). It was not so much Acerbo’s Law that smoothed Mussolini’s path to victory, but the heavy presence of his blackshirts ensuring people voted accordingly. Opposition party meetings had been disrupted, opponents beaten in broad daylight, and, on election day, ballot boxes stolen and their contents tampered with.

While Mussolini basked in the false glory of an overwhelming victory at the polls, socialist politician, Giacomo Matteotti, spoke out against the election, claiming that fraud and intimidation had won it for the fascists. During a parliamentary meeting on 30 May 1924, ignoring catcalls and thinly veiled death threats, Matteotti publicly criticized the fascists. At the end of his impassioned speech, he turned to a colleague and said, ‘And now you can prepare my funeral oration.’

Sure enough, eleven days later, on 10 June, Matteotti was bundled in a car on the streets of Rome, never to be seen again. Matteotti’s disappearance caused a national outcry; people took to the streets calling on the king to depose Mussolini. Mussolini, while comforting Matteotti’s wife and claiming he knew nothing about it, voiced his revulsion over the crime. This, at the infancy of his rule, was Mussolini’s most vulnerable period. The extent of Mussolini’s complicity has long since been debated. There was no proof of Mussolini’s involvement, but he did know the perpetrators, particularly the ringleader, a notorious one-handed thug by the name of Amerigo Dumini, a member of the Ceka, Mussolini’s secret police. Indeed, Dumini presented Mussolini a piece of bloodstained upholstery from the car. In August, Matteotti’s body was found – dumped in a wasteland outside Rome, a knife still sticking out of his chest. Mussolini quickly distanced himself and ordered the trial of the scapegoats. Dumini, together with his Ceka accomplices, was handed a five-year jail sentence, of which he served less than a year.

In disgust at Matteotti’s murder, politicians of all persuasions withdrew from parliament, hoping to force the king into removing Mussolini from office. The ‘Aventine Secession’, as it became known, backfired – the king stood by his prime minister. When, on 3 January 1925, Mussolini faced a vote of confidence, his principal opponents were conspicuous by their absence. Under pressure from the more extreme elements of his party to form a fascist dictatorship, or risk removal, Mussolini took the opportunity to consolidate his power. ‘I and I alone assume political, moral, and historical responsibility for what has happened,’ he said without referring to Matteotti directly. He had, he said, created the climate of violence. But if Italy wanted stability then only the fascists could provide it, even if it took violence to enforce it. It was a pivotal moment in Mussolini’s development. He had survived the Matteotti crisis and, with his opponents absent and weakened, had regained the initiative. The date of 3 January 1925 marked the beginning of Mussolini’s dictatorship.

Читать дальше