Media went from three TV stations to the national launch of another two terrestrials (Channel 4, Channel 5), then came satellite and cable, the launch of commercial radio stations (Kiss, Virgin), and the expansion of magazine publishing houses (Arena, Frank, Esquire, Q, Red and Elle Deco) and more national newspapers (the Correspondent , Today , the Independent ).

TV was exciting – there was The Big Breakfast and The Word , anarchic, youth-oriented shows where the kids were in charge, and there were no rules. Paula Yates could seduce Michael Hutchence in bed live, bands could swear at Terry Christian, Amanda de Cadenet got a speaking part. Of course it wasn’t all creative, and someone had to pay for it. Canny types saw the opportunity to marry up brands with this new sexy media. Brands had the money, Britain was brimming with creativity. One of the most canny was Matthew Freud, whose PR agency brought the two together. His agency could place a packet of crisps on a TV show, or a toothpaste tube on a magazine cover; celebrities could be bought and sold; a soft drink could sponsor a film premiere. It gave PRs and brands the illusion they were in control, and gradually, they were.

Kris Thykier, Freud’s right-hand man, remembers Planet 24’s Christmas parties as ‘legendary’. The year Planet 24 launched The Big Breakfast , its other show The Word was in full flight. Two of the most anarchic TV programmes that had ever been made – produced and presented by young people, for young people. This wasn’t any longer middle-aged men in expensive suits in Madison Avenue and Soho telling young people what was cool. The kids were doing it for themselves.

‘We took over the Ark in Hammersmith, which had just been opened and was the building of the moment. We threw a party on the top floor and it was the first moment where you sensed there were young people in charge. It was the year the Groucho was up and running. I was 20 years old and already representing the programmes, the presenters and the production company, talking to all the newspapers. It was mad. But the media were encouraging it and we were storming it,’ he says. ‘That party that year was the meeting of the teams that made The Word and The Big Breakfast . Two shows, one first thing in the morning and one last thing at night, talking to a generation that hadn’t really been talked to by television before.’

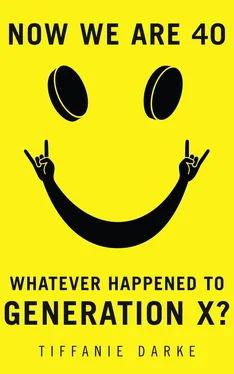

The same thing was happening in the print world. Newspapers began to expand to accommodate all the new advertising streams, with features and lifestyle and fashion sections starting to appear. These sections naturally invited in more staff, many of them young and female. This was where my career took off: I went from being an unpaid work experience on the listings section of the Observer (a job I had blagged through a friend of a friend of a friend), to a paid researcher on their Life magazine supplement. From there I went to the Telegraph as a commissioning editor in charge of food (where my patrician, silver-haired boss called me ‘The Infant Tiffanie’ as I was, as far as he was concerned, outrageously young to be in the job).

Courted by PRs, riding the London cocktail circuit of launch parties and openings, it was the ideal spot to watch the Nineties unfold. Like Thykier, I went to some legendary parties and witnessed some great moments. I remember attending one party in Cannes at the film festival, hosted by MTV in Pierre Cardin’s space-age villa, a collection of pink Teletubby pods built into the edge of a cliff on the Cote d’Azur. Ostensibly the week-long festival in Cannes was a showcase of the film world’s upcoming releases – and they were so exciting, as directors like Quentin Tarantino and Guy Ritchie were bringing a rock ’n’ roll edge to Hollywood.

In 1998 Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels was released, giving London an international film voice – and making it very attractive to brands looking to cash in. There were probably about a thousand people at the MTV party that year, every named DJ in the land playing, and endless test tubes of Absolut Vodka going round. Everyone was cool, young and fashionable. At three in the morning they closed the party down and emptied out the villa – and at four they started it up again, for those that remained. We danced on the terrace as the sun came up over the Mediterranean and there was nowhere cooler or more at the centre of things on earth than that terrace right then – we were all exactly where we wanted to be.

As such a source of economic prosperity, the thriving creative industries, which had previously been dismissed as a bit ridiculous and inconsequential, were now being embraced by the establishment. They were part of Brand Britain – something we could sell on to the world to drive our economy and elevate our national pride. Taking his cue from America, which was so good at marketing itself, the newly elected Tony Blair held an event in 1997 that was to become the pivotal moment of the Nineties. He celebrated his election with a series of parties at 10 Downing Street, and all these artists who had set themselves up as anti-establishment, disruptive voices, were invited to Number 10, the heart of the government.

Blair was Cool Britannia – he had rebranded politics and reinvented it for our generation. For a generation so expert on and obsessed by cool, Blair’s relative youth and embracing of the creative industries was intoxicating. He must be a good thing. One of the first things he did in government was celebrate British design and creativity with a party – a party! Suddenly the emblems of what had previously been considered fringe culture were invited in to be celebrated by the establishment itself. Thatcher had had little time for culture. After 18 years of Tory rule, there were clear changes afoot.

‘It was an exciting time, to have so many people from all these different industries included,’ says June Sarpong. ‘Architecture, design, he had them all. It wasn’t just the obvious musicians and fashion and art.’ Geri Halliwell had just brought the Union Jack in from the cold, Blur and Oasis were fighting it out for cool points, the cast of The Full Monty were on set, the ‘Sensation’ exhibition was about to open at the Royal Academy, Loaded was in full swing. Tony Robinson, Vivienne Westwood, Ben Elton, Chris Evans and Kevin Spacey all trooped up the street to that famous front door. Blair hit cool paydirt when he got the photograph of the decade – chortling over a glass of champagne with Noel.

‘The fact that a guy who’d been in a band, owned an electric guitar and has probably had a spliff was prime minister really meant something,’ said Gallagher later. ‘He might be one of us.’ And Blair knew how to handle himself. When Gallagher asked him how he had managed to stay up all night on the night of the election, he quipped, ‘Probably not the same way you did.’

‘That government, because they were all so young themselves, understood how important shaping British culture was, not just for Britain but as a message to the rest of the world,’ says June. ‘They understood the importance of selling that image so that the world wanted to be part of the UK. It was quite American thinking.’ Politics, then, began to use marketing too: the age of spin was born. Blair’s PR man was Peter Mandelson, a silver-tongued figure hated by the media for his slippery talking, whose responsibility was to cast the New Labour project as the bright dawn of liberal thinking. The danger was that the shiny sheen Mandelson applied to the policies and personalities left them open to suspicion.

Momentarily, Blair brought that disengaged group in from the outside. Ultimately, though, politics did not benefit from its embrace of marketing – in the end its reliance on spin just earned it distrust. By the time Cameron came along with his lookey-likey ‘Cool Britannia’ party (Eliza Doolittle and Ronnie Corbett: the guest list didn’t have quite the same cachet), the cultural zeitgeist had moved on. He would have done better to invite Millennial vloggers and the Silicon roundabout digipreneurs, but of course that just isn’t as sexy or cool. Cameron was a posh boy who went to Eton (nobody likes privilege) whereas Blair presented himself as classless. He may have come from a relatively affluent background and even gone to public school, but Blair was socially much harder to place – the level playing field we all wanted so much.

Читать дальше