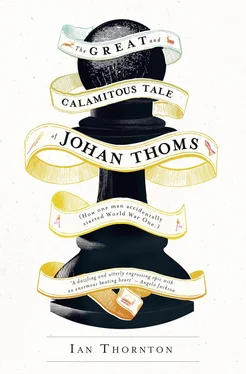

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by The Friday Project in 2013

Copyright © Ian Thornton 2013

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Ian Thornton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007551491

Ebook Edition © October 2015 ISBN: 9780008165932

Version: 2015-09-28

To Heather, Laszlo and Clementine

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue:

A Refracted Tale of Two Wordy Old Gentlemen in a Blue Prism

Part One

1 Around the Time When Adolf Was a Glint in His First Cousin’s Eye

2 Pawn to Queen Four

3 Serendipity’s Day Off

4 The Butterflies Flutter By

Part Two

1 Fools Rush In

2 A Vision of Love (Wearing Boxing Gloves)

3 Drago Thoms: Pythagoras, Madness, and an Indian Summer in Bed

4 The Kama Sutra , Ganika, and Russian Vampires

5 We Are the Music Makers. We Are the Dreamers of Dreams.

6 A Sweet Deity of Debauchery

7 A Day (or So) in the Country

8 Just a Lucky Man Who Made the Grade

9 The Accusative Case

10 The Black Hand

11 The Day Abu Hasan Broke Wind

12 A Microcosm of the Apocalypse

13 A Farewell of Scarlet Wax and Gardenia

Part Three

1 And the Ass Saw the Angel

2 It Only Hurts When I Laugh (Part I)

3 The Die Is Cast (aka Les Jeux Sont Faits )

4 The Unlikely Bedfellow

5 “Ciao Bello!”

6 The March of Don Quixote

7 In No-Man’s-Land

8 “A Shadow Can Never Claim the Beauty of the Image”

9 The Birth of Blanche in a Dangerous Ladbroke Grove Pub

10 Cicero’s Fine Oceanarium of Spewed Wonders (1920–1932)

11 Suffragettes, Mermaids, and Hooligans (1932)

12 Let’s Rusticate Again

13 Jackboots, Cleopatra, and the Bearded Lady (1932–1936)

14 The Girl in the Tatty Blue Dress

15 She Had a Most Immoral Eye (1937–1940)

16 Archibald’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

17 Then There Were Three Again

18 Music, Brigadiers, and Marigold (1940)

19 It Only Hurts When I Laugh (Part II)

20 “Gawd Bless Ya, Gav’nah!”

21 A Giant in the Promised Land

22 Pepper’s Ghost, Fluffers, and a Brief Encounter

Part Four

1 “Everybody Ought to Go Careful in a City Like This” (1945)

2 The Return of Abu Hasan

3 The Brigadier’s Au Revoir

4 The Veil

5 A Blue Rose by Any Other Name

6 Dragons, Confucius, and Snooker

7 “I Know Who You Are!”

8 The Death and Life of a Grim Reaper

Epilogue

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

Prologue

A Refracted Tale of Two Wordy Old Gentlemen in a Blue Prism

A rural cricket match in buttercup time, seen and heard through the trees; it is surely the loveliest scene in England and the most disarming sound. From the ranks of the unseen dead forever passing along our country lanes, the Englishman falls out for a moment to look over the gate of the cricket field and smile.

—J. M. Barrie

2009. Northern England

I sat with my grandfather Ernest in a very comfortable, spacious ward in the hospital in Goole. The doctors had said that he would not live for much more than a week.

Goole is as Goole sounds, a dirty-gray inland port in Yorkshire not far from England’s east coast. More than one hundred years earlier, Count Dracula might well have grimaced as he passed through, en route from Whitby to Carfax Abbey. Most foreigners (and some southerners) think it is spelled Ghoul , especially after their first, and invariably only, visit. This is where Ernest’s final days were to be spent, though at least the hospital sat at the very edge of town and his window faced the more pleasant countryside.

It had been a rapid decline for a man who, well into his nineties, on the eleventh day of the previous November, had walked the three and three-quarter miles to the train station before daybreak. He had traveled south on three trains of varying decrepitude and two rickety tubes to stand by the Cenotaph on Whitehall with thousands of others. Many were bemedaled, some wheelchaired, but each had a shared something behind the eyes and a similar thought focused just above the horizon, as the high bells of St. Stephen’s in Westminster struck eleven and the nation fell silent. Then, with only tea accompanied by Bovriled and buttered crumpets from the Wolseley on Piccadilly as fuel, he had made the return trip the same day, pushing open, with untroubled lungs, his unlatched door way past the time that saw most decent folks in bed. He had told me that it was the only day he could ever remember when he had not conversed with a single person. He had had his reasons.

Now he tugged at a length of clear plastic tubing, which disappeared under sterile white tape and into the wattle of his forearm; an artificial tributary into the slowing yet still magnificent deep red tide within. He did not appear to be uncomfortable. On the contrary, he exhibited a strong and urgent desire to speak.

He gestured toward the clock above his bed with his right hand. “In the story I am about to tell, please bear in mind the possible minor defects and chronological leaps in the memory of a dying man or two. Exaggeration is naturally occurring in the DNA of the cadaver known as the tale. This is important.” He looked straight at me in the way that he always had, in order to let me know that this part of the game was not to be taken lightly.

I do not paraphrase, for my grandfather spoke this way from as far back as I can recall. His deliberate and florid verbals had always transformed the planning, execution, and completion of what for a young lad might otherwise have been everyday chores, into marvelous adventures of joyous nonsense. He turned tuneless whistles into lush arias effortlessly.

He had been my mentor and teacher, instructing me on how to hold a fish knife, stun a billiard ball. He taught me the subtleties and implications of en passant on the chessboard. He knew whether to introduce the team to the Queen or the Queen to the team. He taught me that the correct answer to “How do you do?” is indeed “How do you do?” Of his early life, I vaguely recall references to his days as an emetic, vicious, ear-tugging martinet of a schoolmaster; his inherited connections to and shares in the Cunard shipping line, gained through an ancestor’s good fortune in a Cape Town card game over ever-cheapening rum with bothersome (but luckily pie-eyed and wobbly) pirates; his junior partnership with Sir Thomas Beecham, 1England’s greatest-ever conductor and founder of both the Royal and the London Philharmonic orchestras; dinners with royalty, with Niven and Korda, Gielgud and Fonteyn, Olivier and Churchill. I remember framed monochrome photographs of him at that time, as a young man in a Savile Row tuxedo, Jermyn Street cuff links, well-heeled Bond Street shoes, a heavily starched shirt, and a head of black hair expertly topped off with a light Brylcreem.

Читать дальше