From the opening hours of the Korean War, therefore, the American attitude was to look for a conspiracy emanating from Moscow. This strategic stance would colour much of the policy towards the Korean situation over the next three years. Millions of words have since been written on the role played by Russia and, indeed, China in the North Korean attack. Given the secrecy of those regimes, and notwithstanding the volume of information made available since the collapse of the Soviet Union, historians remain divided as to the extent of Russian or Chinese culpability.

Some things are indisputable. The North Korean Army had been supplied with large amounts of Soviet military hardware, making it a much stronger force than its southern counterpart. Crucially, the armour meant that this was an army capable of offensive operations – unlike Rhee’s. Soviet instructors had been seconded to North Korean units since 1948. Kim was close to the Russians, having spent several years there. He had visited Moscow and Beijing earlier in 1950. It is stretching credulity to imagine that the possibility of invasion was not mentioned. Chinese railways would be needed to maintain the North Korean logistical effort, and, in particular, any resupply from Russia. It is, therefore, difficult to imagine that either China or Russia was entirely in the dark prior to the North Korean assault.

That is some way from asserting, however, that the attack was ordered by Moscow, Beijing, or both. Perhaps the most that can be said is that while it is possible that Kim initiated the attack under direct instructions from Moscow, it is more likely that Stalin’s headquarters at the Kremlin was simply content that it should go ahead.

Russia and/or China may have been willing to take a gamble with Korea at this level – to offer support without full-scale involvement. The Truman Administration was after all emitting confusing political signals during these critical months of the Cold War. Although secretly resolved to confront Communist aggression robustly, a speech by Secretary of State Dean Acheson in January 1950 seemed to concede that Korea was not a vital American interest.

Yet China was in no position to entertain war with the United States. Mao had only recently secured power in Beijing and was much more interested in finishing the war against Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan than he was in new adventures to the north. Chiang’s KMT (Kuomintang) Nationalist forces were now confined to this large island and Mao hoped to invade it. This would eliminate final opposition to Communist rule in China, putting a definitive end to the Civil War there.

Although Moscow had exploded an atomic device in 1949, it was in no position to risk a nuclear confrontation which, in 1950, it would have lost. But if the United States was ambivalent about Rhee’s regime in South Korea, then why not let their ally Kim Il Sung see what he could achieve?

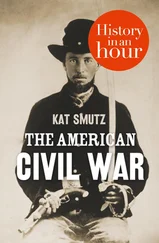

This kind of speculation must have been academic to the South Korean troops thrown into the line across the 38th Parallel in June 1950. Such was their routing, that of the 100,000 men notionally under arms on 25 June, about 80 per cent were unaccounted for after the first week. Rhee himself fled the capital with his key ministers on the 27th. By the 29th, the city had fallen. The bridge across the Han river was choked with refugees as families fled Kim’s troops. South Korean Army vehicles barged through in their panic. The elderly or infirm were run over, some falling into the water. Children lost their parents – sometimes for ever.

South Korean refugees flee the invasion in 1950 (Image by US Defense Department)

The North Korean drive was organized into four fighting columns. Two of them converged on Seoul, one cleared the Ongjin peninsula to the extreme west, and one pushed down the east coast, supported by a small-scale amphibious assault. After the fall of the capital, these were consolidated into two – an eastern and a western thrust.

About thirty miles south of Seoul lies the small town of Osan, spanning the main route south. On the morning of 5 July 1950, elements of the North Korean 4th division advanced towards the town from the north. As they did so they came under fire from infantry and artillery. After a sharp firefight, during which the defenders attempted to knock out several tanks using antiquated bazookas, the attacking North Koreans enveloped the position and the defence collapsed. The poorly disciplined troops scattered, many of them falling prisoner to the advancing Communists, others making their way south in dribs and drabs. Before too long, it dawned on the North Korean commanders that the battalion they had steamrollered consisted of American troops.

They were members of ‘Task Force Smith’: infantry of the US Army. Smith’s five hundred or so troops had not acquitted themselves particularly well. This is perhaps understandable when one considers that they were under-equipped and poorly trained. The first foreign troops to arrive in the Korean theatre, they had been in the country for only four days, hurriedly moved north and put into the first blocking position available. MacArthur’s Far Eastern Command, of which they formed a part, was in poor shape. Starved of men and equipment, they were accustomed to the soft life of garrison duty in Japan. In contrast, Task Force Smith had been outnumbered and outfought by a competent opponent with excellent equipment, training and motivation. If this was to be representative of the American response, then the North Koreans had little to worry about.

Fortunately for South Korea, Task Force Smith represented a lot more than MacArthur’s run-down garrison troops. Already, US Air Force planes were beginning to make their presence felt in the skies above the battlefield. The 7th Fleet had orders to cordon off Taiwan, as well as support operations in Korea. In less than two weeks, the Korean War had spiralled beyond Kim Il Sung’s hopes of a swift and decisive local war.

For the poorly equipped Task Force Smith also represented the initial ground contingent of the UN forces. The Americans were responding to a call to arms from the UN Security Council and had made their troops available on that basis. In the absence of an appointed overall UN commander, MacArthur took on leadership responsibility.

At the international level, events moved very quickly following the North Korean attack of 25 June. That same day, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 82, condemning the North Korean onslaught. By the 27th, Resolution 83 had been passed, calling on all member states to provide military assistance to resist the invasion. Truman immediately ordered American air and naval assets into the theatre and that ground troops should be despatched as quickly as possible. Task Force Smith would be the first of these. Meanwhile, American diplomats set about assembling a coalition of nations willing to support this first real test of UN collective security.

The United Nations, a new organization, was keen to demonstrate the strength of its solidarity. It had been established in 1945 at the instigation of the Allied victors of the Second World War. Importantly, its architects were anxious to avoid the perceived weaknesses of the League of Nations, its forerunner. With far fewer members than today (and most broadly supportive of what might be termed an ‘American-led agenda’) there was the strong sense that the United Nations must not be allowed to fail. The catastrophe of the Second World War was fresh in people’s minds. It was felt that had Hitler been challenged earlier, rather than appeased by the League, then much of the suffering could have been avoided. Attitudes to collective security in the face of breaches of international order were a lot more robust than tends to be the case today.

Читать дальше