Had fate been different, they would have shared their lives and had children, and together grown old. That she would never know what had happened to him was his saddest thought. When the fighting between the British and Italians finally came to an end, someone in Eritrea, maybe even one of the enemy officers who had pursued him, would confirm that he had still been alive several months after the fall of Asmara. But nothing more. She would never know of the dungeon on the other side of the Red Sea, which had cost him so much to cross. Here he would die and be buried and quickly forgotten as the crazed Ahmed Abdullah al Redai. And then no trace in this world would remain of the man he had been.

NAPLES, AUGUST 1935

Amedeo Guillet rested his arms on the railings of the ancient steamer, taking care not to mark his olive-grey uniform, and looked towards the crowd. Ever since he had come aboard, two hours before, they had been slowly gathering, milling about in the shade under the palm trees in the piazza and beneath the glowering grey walls of the Maschio Angioino, the Angevin castle on the city’s waterfront. A dense mass was waiting expectantly at the point where the tree-lined avenue that led from the railway station entered the square, and it was there, too, that the attention of those looking down from the balconies seemed to be concentrated. Tall carabinieri, in full dress uniform of bicorn hats, distinctive white cross belts and swords, were standing together, with studied insouciance, indifferent to the excitement around them. But with Naples reinvigorated by its afternoon siesta, the sense of anticipation in the crowd carried to the quayside where the passenger ships were docked.

Amedeo was surprised at the multitude. Troop ships had been embarking all summer, yet the city seemed determined to see off the last with the same enthusiasm as it had done the first. Every so often the crowd’s steady murmur was ruptured by youths chanting ‘Eià!, Eià!, Alalà! ’, the supposedly ancient Greek war cry that the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio had popularised with the early Fascists. Or one of them would bellow: ‘For whom, Abyssinia?’ ‘A noi! To us!’ came the resounding reply. A noi! ’ It was the latest gimmicky catchphrase put about by the propagandists of the regime. All of a sudden, a ripple spread through the crowd. A second later a roar greeted the arrival of a column of marching men. Amedeo watched as figures began scurrying across the piazza towards them, drawn like iron filings to a magnet. Flowers were thrown to the soldiers or pressed into their hands, and amid the waving and the sea of faces could be seen little flags with the green, white and red of the Italian tricolour. It must have been something like this in May 1915, Amedeo felt, when his father and uncles had gone to war.

The column was mid-way through the throng when the sound seemed to change to a loud and delighted cheer. They were the Alpini, Amedeo could see, mountain troops from the north, whose beards and peaked felt caps made them look a little like William Tell. Children edged to the front, encouraged by smiling mothers who stooped and pointed, for behind the officers and regimental flags at the head of the column were half a dozen German shepherd dogs, leather satchels strapped to their backs. Trained to carry dispatches over frozen Alpine passes, the regiment’s canine messengers were being mobilised for service on the Ethiopian ambas .

Then it was the turn of the Bersaglieri (literally ‘marksmen’) who emerged into the piazza with a fanfare of trumpets and at their customary jog, the cascades of cockerel feathers on their hats rippling through the crowd like merrymakers at carnival. It was the first time, though, that Amedeo had seen their distinctive headdress attached to tropical pith helmets. As they came through the gateway to the port, the foreground to countless paintings of the Neapolitan waterfront, a military band struck up the Hymn of the Piave . For the first time Amedeo, who had been watching unmoved by the scene, felt his emotions stir. No other song of the Great War had such resonance as this melancholic, but defiant morale-raiser, which had been sung to rally the Italian troops after the rout at Caporetto in 1917. Her allies had urged Italy to abandon the whole of the Veneto, as the Austrians, backed by German divisions, broke the front. But the king himself, Vittorio Emanuele III, had brought the shattered army to heal at the river: ‘And the Piave murmured, ‘‘The foreigner will not pass’’.’

The tune changed once more and Amedeo’s attention was drawn again to the piazza, cast in lengthening shadows as the sun gently expired over the Bay of Naples. A legion of Black Shirts had arrived, young volunteers determined to give victory in Africa a distinctively Fascist stamp. And they were singing as they came on. It was that idiotic, jaunty song that had been unavoidable for weeks, and it grew louder as the marching men approached the port:

Faccetta nera, bell’Abissina ,

Aspetta e spera: la vittoria s’avvicina …

Little Black Face, beautiful Abyssinian girl,

Await and hope: victory is approaching …

Amedeo looked down to those gathered on the quay and caught Bice Gandolfo’s eye. They smiled as the men strode past in a swaggering march, swinging their bare forearms, for a black shirt, it seemed, was always worn with the sleeves rolled up. Ethiopia’s days of serfdom, they sang, would be replaced by the slavery of love. Then came the rousing finale:

Little Black Face, you will be Roman

And for a flag, you will have the Italian.

We will march past, arm-in-arm,

And parade in front of the Duce

And in front of the King!

In the cheering that followed, Bice made a dismissive little gesture with one white-gloved hand. Her father beside her, Amedeo’s Uncle Rodolfo, shouted up: ‘I am sure the king would be delighted to meet her!’ And the three of them laughed as the column headed down the quay.

From the far end of the docks, a foghorn blasted. One of the troop ships, festooned in bunting and paper streamers, was casting off. Every available space on deck was filled with cheering men, waving their hats, hurling flowers and last minute protestations of love at their women below. On the ship’s two funnels were giant, stylised, portraits of the Duce, wearing a helmet, jaw clenched in martial resolution, his head thrown back to iron out the chins. Other ships joined in the cacophony, sounding their horns, and then fireworks exploded over the city, jarring its crumbling palazzi down to their tufa foundations as they had so many times before.

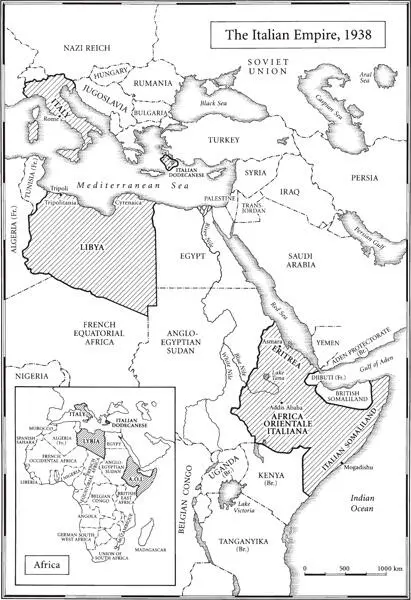

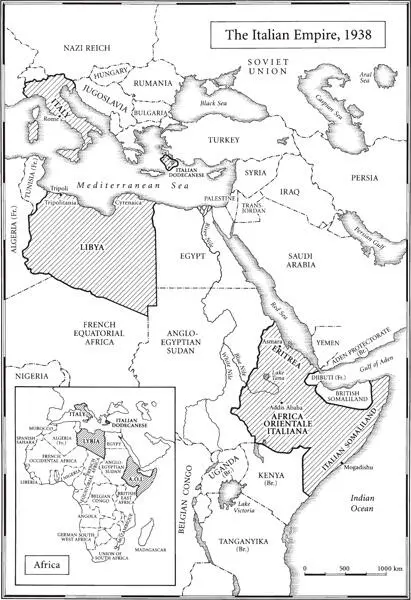

It seemed more like a wedding than war, and the small cluster of friends and relatives gathered at the quay beside Amedeo’s ship were the guests whom nobody knew. With half the Italian army being shipped to Eritrea and Somaliland, little fuss was being made of the old steamer that plied between Naples and Tripoli, the capital of Italian Libya. Amedeo had urged his uncle not to see him off. It would take the chauffeur at least an hour to pick his way back through the crowds to the Gandolfos’ palazzo on the Via dei Mille. But the older man had insisted and Bice, to his surprise, had wanted to come too. Amedeo felt grateful now that they had done so. For although he was bound for Libya, his final destination was the same as that of the cheering men. He, too, would be going to war in Abyssinia if, as seemed inevitable, war it turned out to be.

Читать дальше