When war started the Admiralty was calm and confident. With fifteen battleships, of which thirteen had been built before 1918 (and ten of these were designed before 1914), and six aircraft-carriers of which only HMS Ark Royal was not converted from other ships’ hulls, it knew exactly what sort of war it was going to fight. Unfortunately Germany’s naval staff, the Seekriegsleitung (SKL), had a different rule book.

A less parsimonious British government or a more realistic Royal Navy might have expected the Germans to break their agreements, but the interwar years had been noted for self-delusion, and the admirals did not readily learn lessons. The Royal Navy seemed indifferent to the threat of air attack. Its multiple pom-pom anti-aircraft guns had proved completely ineffective, but only when war was imminent were Swedish Bofors and Swiss Oerlikon guns put into production.

A closed eye had been turned to the potential of the submarine. With lofty disdain, most Royal Navy officers regarded the submarine service as a refuge for officers of low ability. Submarines participating in fleet exercises were always ordered to withdraw during the hours of darkness. Anyone who suggested that in a future war the enemy might not be willing to withdraw during the hours of darkness was told that the miracle apparatus asdic could counter submarines.

Asdic (later named sonar) was a crude device first introduced at the end of the First World War, although never used operationally in that war. Mounted under a ship’s hull, it emitted sound waves and picked up their reflections to detect submarines. Always demonstrated in perfect weather by well-rehearsed crews, it enabled a confident Admiralty to declare the U-boat to be a weapon of the past. By 1937 the Naval Staff said that ‘the submarine would never again be able to present us with the problem we were faced with in 1917’. Even if the Admiralty’s assessment of asdic had been right, there were only 220 warships equipped with it, while the British merchant service had 3,000 oceangoing ships and 1,000 large coasters to be protected.

The range of the asdic was a mile at best. It could not pierce the layers of differing temperature and salinity that are commonly found in large bodies of water. Nor could it be used by a ship steaming at more than 20 knots, or in rough weather. It was useless in locating a surfaced submarine and did not reveal the depth of a submerged one. All of these shortcomings could benefit a skilful U-boat commander, and it might have been remembered that by the end of the First World War attacks by surfaced U-boats had become the favoured tactic.

Admirals everywhere prefer big ships. The United States navy lined them up in Pearl Harbor and, even in the middle of the war, German admirals were still telling each other that the battleship was the most important naval weapon and pressing for a programme to build more and more of them. So the British navy, like the United States navy, began the war with plenty of expensive battleships for which there was little or no need and a grave shortage of small escort vessels.

Canada wanted to make a contribution to the war without having its soldiers decimated at the commands of British generals on some new ‘western front’. It elected to concentrate on ships, which could be kept under its own control. The Canadian navy started a construction programme exclusively devoted to escort vessels – corvettes and frigates – to protect the Atlantic traffic. The corvettes were slow and seaworthy, although the way in which they rolled and wallowed from wave top to wave top made crewing them one of the war’s most queasy assignments. Nevertheless by May 1942 Canada had 300 ships – a magnificent achievement.

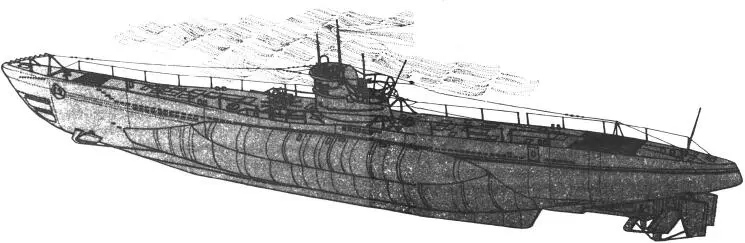

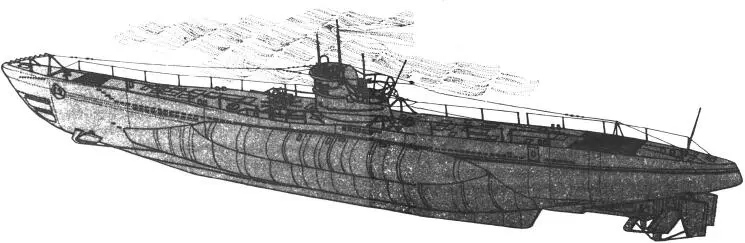

FIGURE 2

German submarine U-boat, type V11C

Since the First World War, submarine design had improved only marginally, and then chiefly in greater hull strength. This enabled them to dive far deeper, and provided escape for many U-boats under attack. (Due largely to inter-departmental squabbles, it took some time before British depth charges were designed for deep water use.) Although more efficient electric batteries enabled submarines to stay submerged longer, they still spent almost all their time on the surface, submerging only to escape attacks from the air or avoid very rough seas.

A submarine of this period consisted of a cylindrical pressure hull like a gigantic steel sewer pipe. To this pipe, a stern and bow were welded and the whole vessel was clad in external casing to give it some ‘sea-keeping capability’, although submarines could never be manoeuvred like ships with regular hulls. A casing deck and a conning tower – what the Germans called an ‘attack centre’ – was added to the structure. Directly below the conning tower was the ‘control room’ where the captain manned the periscope. The tower was given outer cladding to provide some weather protection to men standing there, as well as some measure of streamlining when the boat went underwater. An electric motor room and an engine room with supercharged diesels of about 3,000 bhp were positioned well aft for the sake of sea-keeping and to cut diving time. The great bulk of a submarine was below the water-line, and visitors going below are always surprised to discover how big they are, compared with the portion visible above water. For instance, the long-range Type IXC U-boat that displaced 1,178 tons submerged would still displace 1,051 tons when on the surface.

There were two basic types of German U-boat used operationally in the Atlantic campaign, the big long-range Type IX and the smaller Type VII, which was the standard German U-boat of the Second World War. 5The VII typically had a displacement of 626 tons, a crew of four officers and forty-four ratings (enlisted men), and carried about fourteen 21-inch torpedoes. Four tubes faced forward and one aft. All the tubes were kept loaded and when they had been fired, the awkward business of reloading had to be done. On the surface the diesel engines gave a range of 7,900 nautical miles at 10 knots. If they pushed the speed up to 12 knots it would reduce their range to 6,500 nautical miles. In an emergency the diesels could give 17 knots for short periods. With a fully trained crew a Type VII dived in thirty seconds and when submerged used electric motors. The rechargeable batteries could go for about 80 nautical miles at 4 knots. Maximum speed underwater was reckoned to be 7.5 knots, depending upon gun platforms which obstructed the water flow. Most reference books give manufacturer’s specification speeds which are faster than this.

The whole purpose of the submarines was to fire torpedoes. These big G7 – seven metres long – devices were no less complicated than the submarine itself, and in some respects exactly like them. They were treated with extraordinary care. Each torpedo arrived complete with a certificate to show that its delicate mechanisms had been tested by firing over a range. It had been transported in a specially designed railway wagon to avoid risk of it being jolted or shaken. One by one, with infinite concern, the ‘eels’ were loaded into the U-boat, which was usually moored inside a massive concrete pen. From then onwards, all through the voyage, each and every eel would be hung up in slings every few days, so that the specialists could check its battery charge, pistols, propellers, bearings, hydroplanes, rudders, lubrication points and guidance system.

To make an attack it was necessary to estimate the bearing and track of the target. Usually the submarine was surfaced, and the captain used the UZO ( U-Boot-Zieloptik ) which was attached to its steel mounting on the conning tower. This large binocular device had excellent light-transmission capability, even in semi-darkness, and from it the bearing, range and angle of the target vessel was sent down to the Vorhaltrechner . This calculator sent the target details to the torpedo launch device, Schuss-Empfänger , and right into the torpedoes, continuing to adjust the settings automatically as the U-boat moved its relative position. By means of these instruments the U-boat did not have to be heading for its target at the moment of launching its torpedo. The torpedo’s gyro mechanism would correct its heading after exiting the tube. Thus a ‘fan’ of shots, each on a slightly different bearing, could be fired without turning the boat. This device was coveted by British submarine skippers who aimed their torpedoes by heading their submarines towards the target.

Читать дальше