A Journey from Zanzibar to the Cape

William Collins

An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition 2000

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 1999

Copyright © Stephen Taylor 1999

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

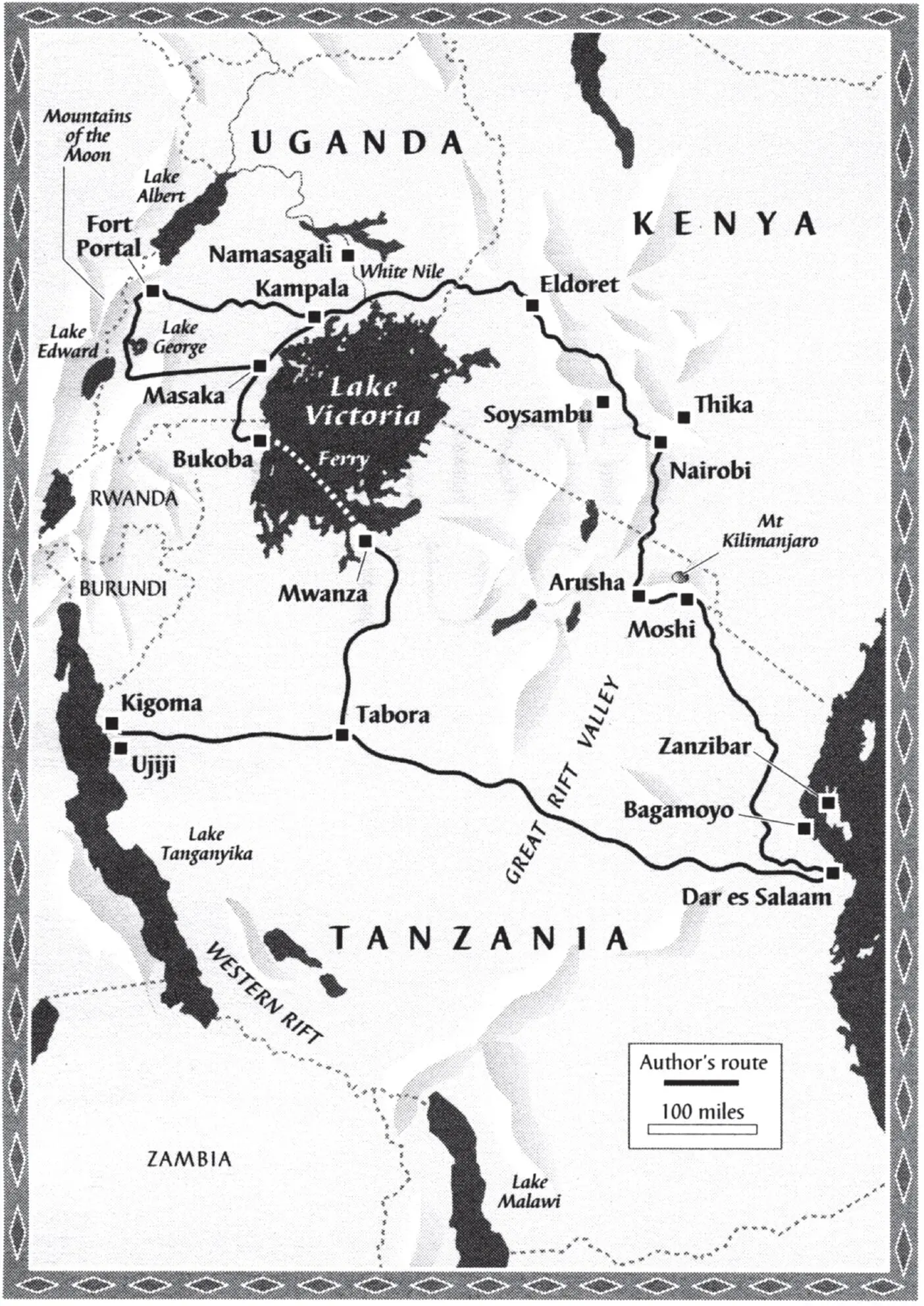

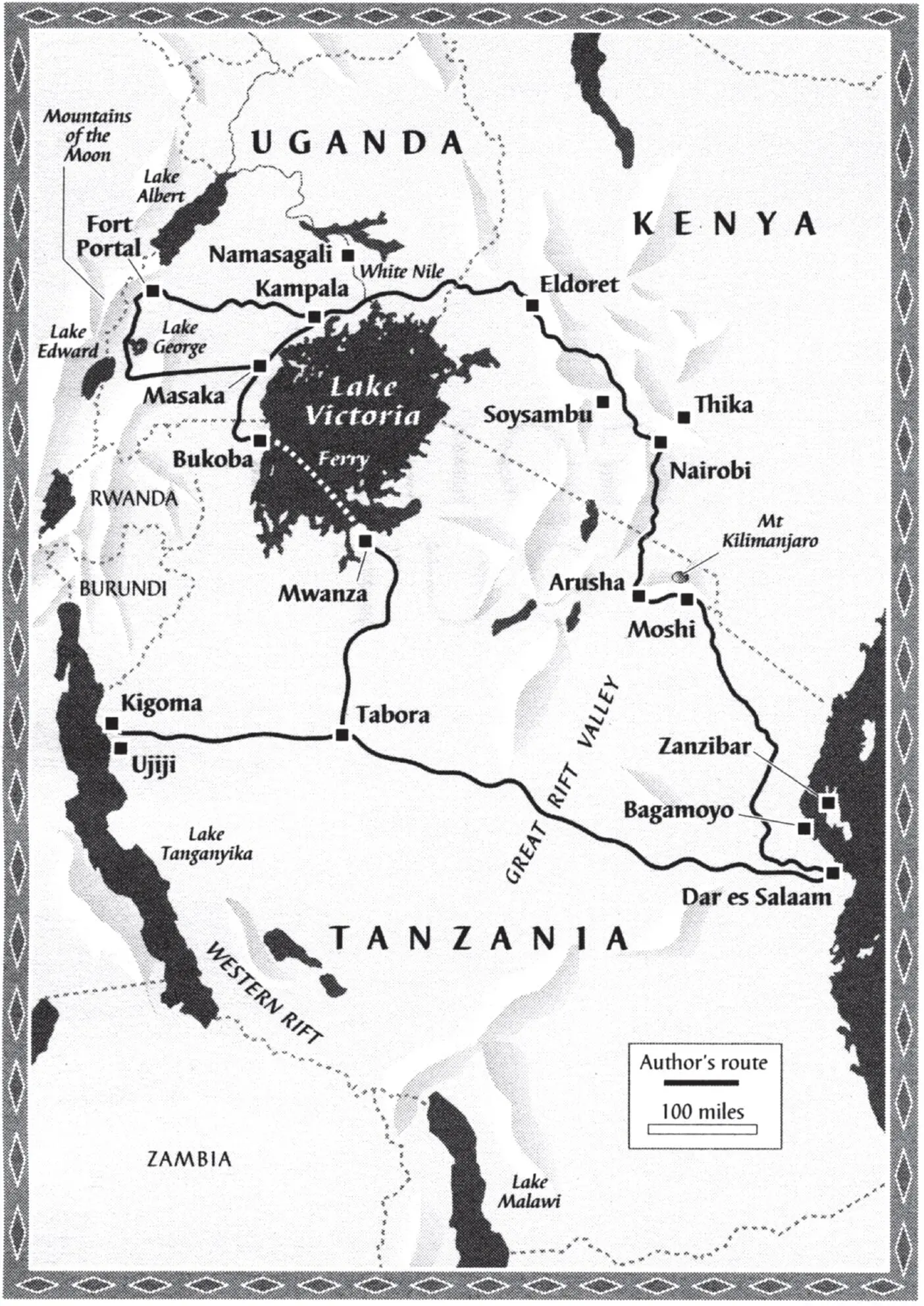

Maps copyright © Duncan Stewart 1999

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780006550693

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN 9780007394661

Version: 2016-01-12

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

To my children, Wilfred and Juliette

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

PART ONE GOING OUT

1. The Island

2. The Coast

3. The Inland Sea

4. The Nyanza

5. The Enclave

6. The Hills

7. The River

8. The Mountains

9. The Valley

10. The Plains

11. The Steppe

PART TWO COMING BACK

12. The Lake

13. The Mission

14. The Escarpment

15. The Plateau

16. The Ridge

17. The Kraal

18. The Reef

19. The Bay

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

THIS IS AN ACCOUNT of a journey in search of a dying tribe. Even at the time I was travelling, in 1997, it was clear that whites as an ethnic minority were doomed in most parts of Africa. It seemed as though the colonial era had belonged to another century rather than to the previous generation. In Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi and Zambia the whites had all but disappeared; in Kenya they clung on diffidently. In Southern Africa, however, there remained hope. Although politically redundant, their economic influence appeared to assure them a future.

My interest in the whites who stayed on in what used to be rather quaintly known as ‘Black Africa’ dates back to the imperial retreat. From the bastion of South Africa, I grew up in the 1960s observing what became a familiar process. As each new African state acquired its independence, the old colonial hands would decamp. Some returned to Britain, but most flinched from the prospect of rationed sunlight and costly alcohol. Ultimately, much of this human debris was borne by the winds of change to South Africa.

The fact that the withdrawal coincided with the seemingly unstoppable rise of apartheid helped shape my own response to these events. When self-styled refugees from African rule came among us, bursting with the same racism as the dour, resentful xenophobes in charge of our own society, it seemed only natural to identify with those they had left behind. Even when the promise of uhuru gave way to cupidity, corruption and worse, the whites who continued to identify with African aspirations to the extent of sharing their fate acquired a certain defiantly heroic status.

At the same time I confess my own attitude to the continent was ambivalent. When I felt compelled to leave South Africa, in the 1970s, it was not to the black states to the north that I looked to make my home but to the motherland of my British antecedents. Only in 1980, and the coming of independence to Zimbabwe, did I feel the summons to test years of conviction by going to live in an independent African state. In the end I stayed for four years.

Since the first publication of this book, Zimbabwe has returned to the headlines. On page 203 I describe visiting a farmer friend, Alan. His efforts had brought him prosperity and his workers conditions that were the envy of all who knew them. I was intoxicated at the time by a heady fusion of landscape and memory, wondering whether I might not yet return to Africa again. Alan – sceptical and pragmatic – was, however, more alive to the precarious status of whites. His words were to be prophetic. The tide of venomous racism whipped up by Robert Mugabe in the election campaign of June 2000 led to almost a thousand white farms being invaded by squatter gangs. Alan and his family were among hundreds forced to flee their homes. His workers paid a severe price for their loyalty; a third had their homes razed.

The land seizures in Zimbabwe had an eerie echo of events in post-independence Tanzania and Uganda. There too white farmers and planters were dispossessed in the name of agricultural and political reforms that proved to be disastrous. In Uganda, at least, lessons were learnt. In the midst of the turmoil in Zimbabwe, an official Kampala daily newspaper said that Uganda needed commercial growers and proposed that land be offered for white Zimbabweans to settle.

Nevertheless, the overall effect was devastatingly harmful. Africa watched helpless as one of its last productive economies was ruined by the same instincts, and the same methods, that had proved so self-destructive in the past.

At the end of my journey I reflected that only time will tell whether whites are capable of enduring in Africa. In just three years the prospects look less auspicious than they did even then. Increasingly parents, not only in Zimbabwe but also in South Africa, see their children attempting to make lives abroad. Inevitably, it is those with abilities and qualifications who are best able to leave. And as the brightest and most adventurous depart, the chasm between Africa and the developed world continues to widen.

THE DIRT ROAD FROM Dar es Salaam petered out at a hedge of bougainvillea. Off to one side lay the shell of a deserted hotel amid palm trees that hung darkly at the edge of the Indian Ocean like bats. Beyond the purple blossoms, on the verandah of a cottage, stood a tall, grizzled white man in a T-shirt, sarong and sandals made from car tyres. ‘And you must be Stephen,’ he said.

He motioned to a seat on the verandah which looked out over the pale sea. A pot of pitch-like coffee was produced and served, in the Muslim manner, in tiny cups. He looked at me intently, a rather forbidding figure with the head of a patrician, a great beak of a nose, thinning white mane and beard, and watchful eyes. I felt apprehensive. My letters had gone unanswered and my presence was unbidden. Now I was expected to explain myself.

I was interested, I said, in whites who had stayed on in Africa. I was starting a journey in the footsteps of the explorers, missionaries and settlers, along the routes of imperial advance and retreat, looking for those who had made their home in post-independence Africa, who had lived through coups and wars, and learnt to live with the corruption, the collapse of services and the generally miserable lot of the African citizen. In particular, I was interested in those who had faith in Africa and its people, and who believed it still had something to offer the world. And now that the last protective white laager had fallen, I was looking for lessons on how they might endure in South Africa.

Читать дальше