I nodded. ‘But that was last week,’ I said, as we headed back downstairs. ‘I thought I might have heard back by now. I might call him later, as it happens. See what the score is …’

Riley rolled her eyes. ‘You just can’t do it, Mum, can you?’

‘Do what?’ I asked her.

She burst out laughing. ‘Do nothing!’

I didn’t call John in the end. After all, if he had a child for us he’d have called me about them, wouldn’t he? But there was no denying I leapt for my mobile when I heard it buzzing at me the following afternoon. Riley was spot on. I was no good at doing nothing. And since I couldn’t take a job – that was a stipulation for our kind of intense fostering – without a child in, I’d soon be climbing all those freshly painted walls. There was only so much cushion plumping a woman can do and stay sane – even a clean freak like me.

And it wasn’t just through lack of an occupation that I was bored. Now we’d moved house, Mike, who was a warehouse manager, had a slightly longer journey to work and back every day, and with us new to the area, filling the day was itself a challenge. I needed to get out and about, make new friends and get to know the neighbours. But all of these things would take time.

It was also still winter, the days short and mostly murky, not really conducive yet to ambling round the neighbourhood, striking up conversations with strangers. And though our new garden was delighting me almost daily with tantalisingly unidentifiable green shoots, I’d never been much of a one for sitting around. I might be a grandma, but I was still only forty-four. A new challenge was exactly what I wanted.

I was in luck. I picked up my mobile to find John’s name on the display. ‘John,’ I said. ‘How very nice to hear from you. Are we on?’

‘Yes and no,’ he said, piquing my interest immediately. ‘Though, if you’re up for it, it’s going to be something of a change of plan.’

‘Oh?’ I asked, intrigued, pulling out a kitchen chair to sit down. He sounded a little tired and I wondered what he might have been up to. His wasn’t an everyday sort of job, for sure.

‘Well, if you and Mike are amenable, that is.’

‘You already said that,’ I said. ‘Which sounds ominous in itself.’

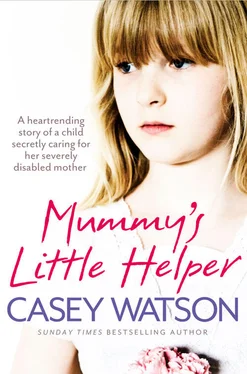

‘Not at all,’ he was quick to correct me. ‘Not in the way you probably mean, anyway. I mean as in we’re no longer planning on lining you up with that lad we talked about. Got something of an emergency situation on our hands. It’s a girl. Nine years old. Rather unusual scenario for us. I’ve spent most of the day at the General as it happens.’

‘The hospital?’

‘Yup. Got a call from social services first thing. The mother’s quite ill. She has multiple sclerosis –’

‘Oh, the poor thing.’

‘Yes, the whole situation’s pretty grim, frankly. Collapsed this morning, by all accounts, while out trying to buy her daughter a birthday present – she’s going to be ten soon. The little girl’s called Abigail, by the way – Abby – and she’s obviously terribly distraught. Looks like Mum’s going to have to be hospitalised for a period. And there is no other family, which means they have no choice but to …’

‘… take her into care?’ My heart went out to her. The poor child. Not to mention the poor mother. Having their lives ripped apart so suddenly like this. ‘No family at all?’ I asked.

‘Two second cousins, that’s all, both of whom live hundreds of miles away. And they’re not remotely close. Never even met the daughter, let alone know her. So it’s not workable. The last thing anyone wants is for little Abby to be dragged off somewhere, when Mum’s here in hospital, as you can imagine. So she’s had a social worker appointed – Bridget Conley. Have you come across her?’

The name was familiar, but I didn’t think our paths had yet crossed. But I was more interested in how Mike and I fitted into this. From what John was telling me this was a pretty straightforward scenario. A routine foster placement while a care package was presumably put in place for the mother so that they could both go home. Short term. Crisis management. Not the sort of thing Mike and I were needed for. Our speciality involved long-term placements and a defined behaviour-management programme, and was usually for kids who’d been in the care system a long time already and/or had come from profoundly damaging backgrounds. I said as much to John.

‘Ah, well, that’s where this isn’t quite what you might expect, Casey. The mum’s had MS for years. Periods of remission here and there, thankfully, but her condition is quite advanced. The fact that she made it into town at all was something of a miracle, apparently. She’s pretty much housebound and quite profoundly disabled …’

‘So how’s she been managing to look after her little girl, then? You say there’s no family …’

‘Not much of anything or anyone, really, it seems to me. Certainly no care or support in place. She’s mentioned a neighbour, but we’ve already had a clear impression that in terms of who’s looked after whom, it’s been the other way around. Little Abby’s been her carer, pretty much.’

Which was a sobering thought, but still didn’t fully answer my question. ‘But why us?’ I asked again. ‘I mean, we’re obviously happy to step in, you know that. But if it’s only going to be temporary …’

‘It’s not going to be that temporary,’ John corrected me. ‘That’s what we’ve been thrashing out today. The medics have given Mum a less than good prognosis, and there’s no way in the world they’re ever going to discharge a sick patient back to the care of a nine-year-old girl. Bottom line is that even if they manage to get her stable and home, and a package of medical support put in place for her, she’s clearly not going to be in a position to care for her daughter, which leaves social services with no choice but to take responsibility for Abby, doesn’t it? That’s the truth of it. Now the genie’s out of the bottle, so to speak …’

And the cat out of the bag, come to that. John was right, of course. Now they knew about it, they couldn’t un-know it. Which left everyone concerned in the worst of all situations. ‘God,’ I said, as the enormity of it hit home for me. I tried to imagine being told I could no longer look after my own children. Having to watch them being taken away from me, when they needed me. It hardly bore thinking about. ‘Poor, poor woman,’ I said to John. ‘She must be beside herself …’

‘Completely distraught,’ John agreed. ‘As you can imagine. But not stupid. She knows there’s no other choice here.’

‘And the poor little girl … how on earth is she dealing with all this?’

‘Badly,’ John said. ‘Which is where you and Mike come in. Because now we’ve met her we don’t think she’s suitable for mainstream care, basically. We’ve had a long chat with Mum this afternoon, and she wants what’s best for her child, after all.’

‘Of course …’

‘And, well, we’re all of the opinion that Abby might be, well, how shall I put it? A little idiosyncratic. I must stress that this isn’t coming from Mum, before you ask. It’s just our assessment, based on what Bridget has seen, and from what we know of how the two of them have been living. I’m obviously not conversant with all the details, but the bottom line would seem to be that this particular nine-year-old is not like any normal nine-year-old. She’s been caring for her mum from a very young age, and has basically had no sort of childhood. I know it sounds daft and, yes, we could be over-dramatising this, but our feeling is that being with you and Mike, and doing the programme kind of back to front, if you like, would give her the best chance of getting back on track. You know, getting her used to living as a child again, basically.’

Читать дальше