If built, Har Homa will close the last gap in a half-moon of Jewish settlements constructed on hilltops around the outer edges of Arab east Jerusalem. By encircling the Arab area with these self-contained Jewish townships, right-wing Israelis want to create ‘facts on the ground’ to ensure they will never have to cede an inch of Jerusalem to the Palestinians, who claim east Jerusalem as their capital.

Under the Oslo accord, the final status of Jerusalem is supposed to be decided in talks scheduled to conclude in 1999, but Palestinians argue that there will not be much to talk about if Israel keeps building. Netanyahu showed no sign of backing down. ‘I am building Har Homa this week and nothing is going to stop me,’ he said in an interview. The Israeli cabinet on Friday reaffirmed his decision, and government sources said the bulldozers are likely to move in tomorrow.

The army will no doubt be called in to keep back protesters, who have vowed to lie down in front of Shem-Tov’s machines. Palestinian leaders have pledged that the demonstrations will be peaceful, but emotions are running so high among Palestinians that they are widely expected to explode into violence. ‘The minute the bulldozers go in I think only God knows the consequences of what will happen,’ said Saeb Erekat, a Palestinian minister involved in the Israeli–Palestinian negotiations.

Yesterday Arafat made a last-ditch effort to thwart Netanyahu diplomatically. Amid Israeli condemnations, he gathered American, European and Arab sponsors of the peace process to an emergency conference at his seaside headquarters in Gaza to seek their help in stopping the Har Homa settlement and putting the peace process back on track.

Although the Americans used their veto in the United Nations vote, they showed their opposition to the settlement plans by sending Edward Abington, the American consul in Jerusalem, to the talks, despite a direct Israeli request that Washington should boycott the meeting. The Palestinian president is making no secret of his anger. ‘The situation is really serious,’ Arafat told envoys to yesterday’s meeting. ‘We are facing a plan to destroy the peace process.’

The conference in Gaza is not expected to make any difference on the ground. Arafat called the meeting to send a signal to Netanyahu that he is not alone; the governments who sent envoys wanted to reassure Arafat of support, which they hoped would head off an explosion of Palestinian violence.

The threat of bloodshed is no secret. Under the codename Thornbush, Israeli army units with tanks have been practising manoeuvres to re-enter cities on the West Bank controlled by Arafat’s Palestinian authority, in case Palestinians fight to stop the building at Har Homa. Israeli intelligence sources said yesterday that the army wanted to be better prepared than it was in September, when 60 Palestinians and 15 Israeli soldiers were killed in clashes after Netanyahu’s decision to open a tunnel in Jerusalem.

Given the reluctance on both sides to fight, there is still a good chance violence can be avoided. Crises have come and gone since Netanyahu’s government took over from Labour in May, and generally he has compromised.

Nor is Arafat in a strong position. His army is no match for the Israeli forces. If he had to fight, the peace process that would finally win a homeland for Palestinians would be shown up as a failure. He would then be vulnerable to Islamic extremists.

Netanyahu needs the support of the ultra-right-wing parties in his coalition government. But he may well have miscalculated the strength of anger his moves have inspired among Palestinians. The test of that will come when the bulldozers close in on Har Homa.

Arafat encircled in battle for Jerusalem

6 April 1997

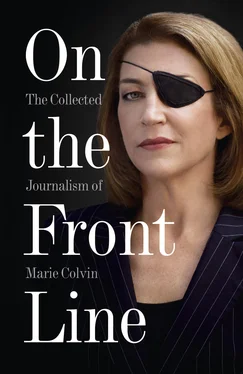

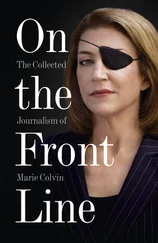

In his first interview with a foreign journalist since the latest Middle East crisis erupted, the Palestinian leader tells Marie Colvin in Gaza why the new Israeli township must be stopped.

It was an odd spectacle: Yasser Arafat marched briskly around his modest office, arms swinging, eyes fixed on the carpet. He might have been deep in thought. But the diminutive Palestinian leader calls his compulsive pacing ‘speed walking’, a form of daily exercise that seems a perfect metaphor for his political predicament: he has little room for manoeuvre.

Sweating in the heavy military jacket he wears in all seasons, he marched round and round on Friday, skirting the conference table and ignoring the breathtaking view from his windows of the sparkling Mediterranean sea. After half an hour’s wear of the dull, grey carpet, he sat down, mopped his forehead with a yellow Kleenex and turned his attention to a visiting reporter.

On his desk were reports of yet another day of violent Palestinian protests in the West Bank against the decision by Binyamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, to build a new Jewish settlement in Arab east Jerusalem.

‘I am asking Netanyahu to understand exactly the sensitivity of the question of Jerusalem,’ Arafat said, swivelling his chair to face the sea, then turning it abruptly back again. ‘I am astonished at how he does not understand it. Or perhaps he understands it but insists on challenging the Palestinians, Arabs, Christians and Muslims.’

On the eve of Netanyahu’s summit with President Bill Clinton tomorrow, Arafat knows he has no alternative but to continue the Israeli–Palestinian peace process. Yet if he accepts the new Jewish township he will lose any credibility among his own people.

From the Israeli side, Arafat is faced with overwhelming force and an intransigent prime minister. The Americans, meanwhile, are pressuring him to halt street protests. They also want him to arrest extremists who have dispatched three suicide bombers to attack Israel since the bulldozers began clearing the way for homes to be built for 30,000 Jews on a pine-covered hill known as Har Homa to the Israelis and Jebel Abu Ghneim to the Palestinians.

An Arab League decision last week to sever Arab ties with Israel gave Arafat some support for what he calls ‘the battle for Jerusalem’. But the backing of other Arab countries has been largely rhetorical. Thus Arafat feels very much alone as he marches in his headquarters by the sea.

For his part Netanyahu, say those who know him, believes that if he can force Arafat to accept the new settlement, the Palestinians will ‘lower their expectations’ in future peace talks. Yet Arafat, already under attack for conceding too much to the Israelis in the Oslo agreements, cannot give up any more if he is to survive as leader.

‘Netanyahu must stop this settlement on Jebel Abu Ghneim,’ he insisted, adding that this was a condition for Palestinians returning to the peace talks. ‘Netanyahu must return to the honest and accurate implementation of the peace process. Nothing less.’

Arafat says he has ‘no contact’ with Netanyahu these days. He has ordered his security chiefs to stop sharing intelligence information with their Israeli counterparts. Netanyahu’s generals have warned that this is dangerous. Since Arafat took over Gaza and the West Bank cities, shared information from Palestinian security forces has prevented several planned attacks against Israeli targets.

But the Palestinian leader has lost faith in any idea that Netanyahu can be a partner in the peace process. Instead, he sees him as dangerously dependent for his political survival on the support of religious and ultra-right-wing parties who believe in Eretz Israel, or greater Israel.

‘I am sorry to say Netanyahu is following the ideology of the (Jewish) fanatic groups,’ said Arafat. ‘He must remember he is committed to Oslo, which was signed by the previous Israeli governments, or we will be at a real impasse.’

Читать дальше