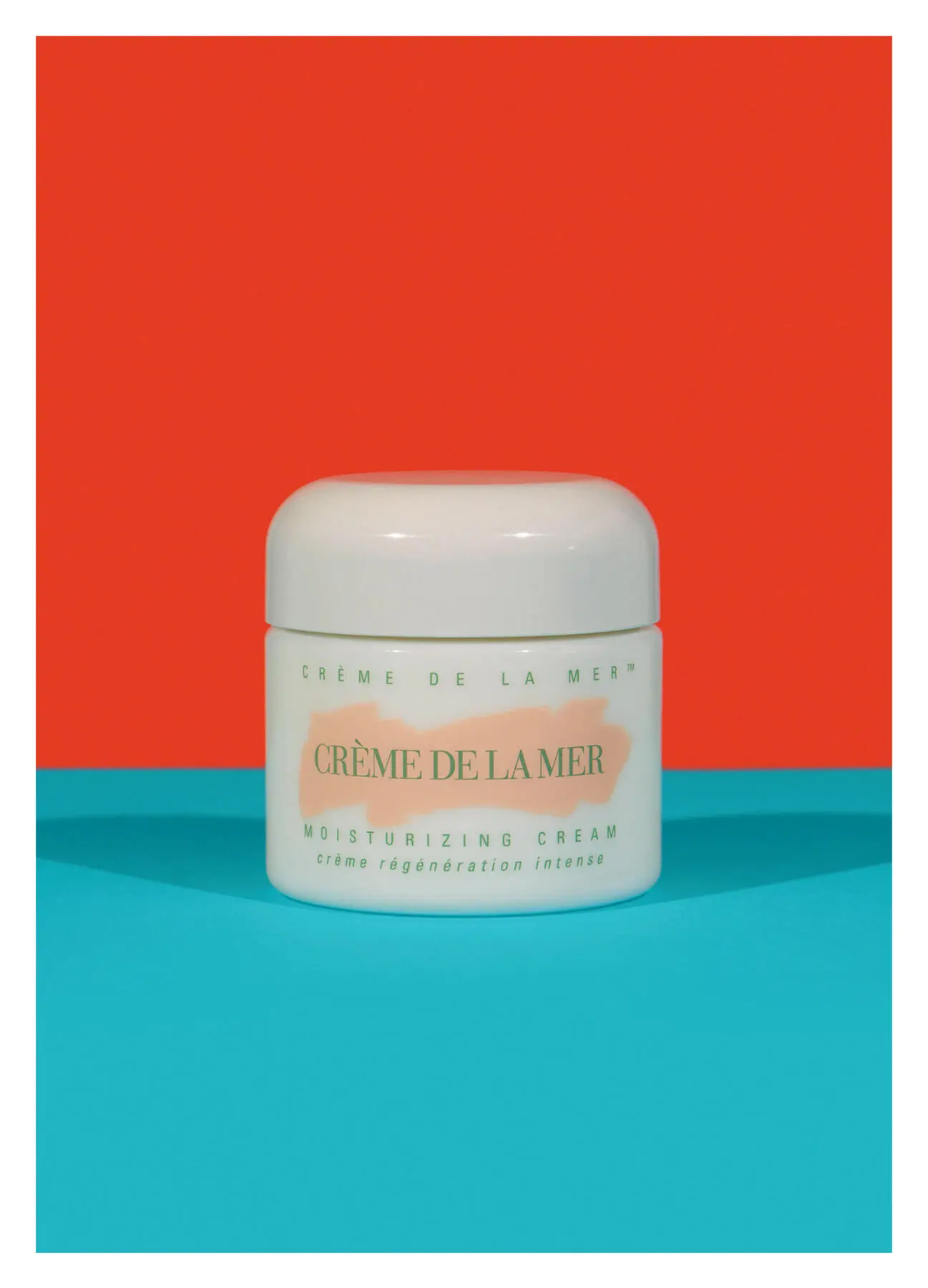

Personally, I use this simple, uncomplicated, pleasurable cream as a skin saver when things go pear-shaped, not as a daily moisturiser, and certainly not as an anti-ageing cream. I suggest people should manage their expectations on that score – this is not a wrinkle cream, or an exfoliant, or an antioxidant of any remarkable merit. It’s a softening, soothing, rich, buttery moisturiser that looks and feels luxurious. You can certainly do as well for much less money and those with oily or combination skin are unlikely to find the original Crème suits them (bafflingly, it contains mineral oil. Some of the other products in the range, like the oil, do not). But nonetheless Crème de la Mer is an icon. Its launch, cachet and subsequent success absolutely marked a sea change in skincare – perhaps an unwelcome one, since in terms of exclusivity and high price point, it’s now far from unique – and, I think, helped spark an increased public interest in skincare. ‘It-creams’ (a term invented by the media for Crème de la Mer, but applied at one time to any cream over £50 – oh, but were that still exceptional) now exist in the portfolio of almost every luxury brand, and yet truly there is still no product more coveted, more intriguing to the average consumer after all these years, than Crème. So there is my answer. Imagine how many polite party-goers wish they’d never asked.

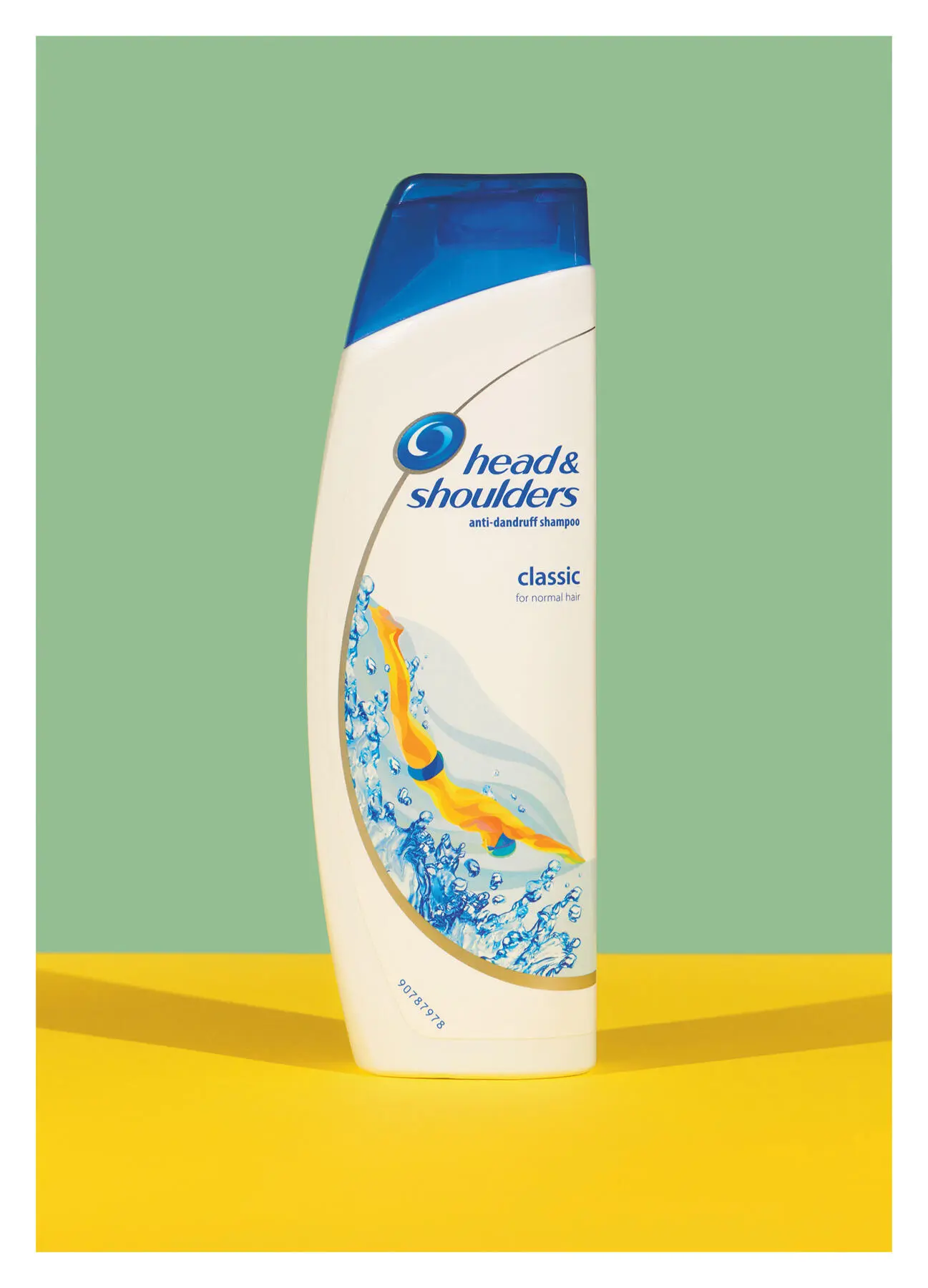

I knew about Head & Shoulders before I even knew what dandruff was. The weird vase-shaped bottle lived around our bath and on TV commercials featuring brooding male models slowly raking their side partings to reveal for the camera an infestation of props department snow. They’d then lather one side of their scalp with Head & Shoulders, the other with a generic shampoo, the miraculous results shown on split-screen TV. It wasn’t until secondary school, and I discovered the pitfalls of wearing the regulation black cardigan, that I realised why – a few Timotei fanciers aside – seemingly everyone used Head & Shoulders. And it’s a credit to P&G’s clever marketing that a potentially embarrassing problem like dandruff became so normalised that the shampoo was such an accepted mainstream beauty staple. Celebrities such as Jeff Daniels, Ulrika Jonsson, Sofia Vergara, Jenson Button and now premiership goalkeeper Joe Hart have all cheerfully cashed a cheque regardless of the inherent implication they have scalp fungus. And why not?

Head & Shoulders is still the world’s bestselling shampoo, still has a strong, slightly chalky whiff of big box washing powder, and to give credit where it’s most due, it still works – with a couple of caveats. Head & Shoulders uses zinc pyrithione to control the levels of micro-organisms on the scalp (the most common form of dandruff comes from yeast growing in skin sebum) and so can only do its job for as long as you’re using it. If you stop, or dramatically cut down, your dandruff will return. And back to my school cardigan: I soon found that Head & Shoulders had little or no effect on me, because I didn’t have traditional dandruff from oiliness and sebum. I just had a dry scalp. If you’re the same, seek out a shampoo – preferably sulphate-free – for this specific problem and treat your scalp to the odd olive oil massage the night before shampooing. You’ll see much lighter snowfall.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned it previously, but I hate most mascaras. Which is an inconvenience if you’d sooner saw off your big toe than never wear it again. My issue with it is that it’s not good enough. I so often despair of how little progress the industry has made over the years in developing just one mascara that does everything I want: separate, curl, define, darken, thicken, lengthen, lift, stay, remove. On shoots, make-up artists will invariably use several different mascaras on just one model. Maybe a Maybelline to build up, a little Tom Ford to kick out at the sides, some MAC Gigablack to really blacken, some Kevyn Aucoin tubing to lock the whole thing down … Now brands are pushing this whole (potentially very lucrative) mascara portfolio nonsense, but really, who on earth has the time? I’m lucky to get two coats on between Brighton and Hayward’s Heath, never mind rustle around for different wands for different jobs.

But what I’ve found, time and time again, when looking into the make-up bags of industry figures as pushed for time and space as the rest of us, is this. When it comes to mascara, most experts will agree that Lancôme is a safe pair of hands. They know their mascara better than almost anyone and for a number of years were head and shoulders above the competition. They make no attempt at subtlety (natural-looking mascaras are the chocolate teapot of beauty), but go all out for the kind of fluttery, separated and thickened lashes most of us desire. The formula of Hypnôse is neither wet and messy, nor dry and spiky. It stays fresh for longer, the expertly designed brush coats each and every lash perfectly. The black is real black, not some insipid shade the colour of a faded sock. It is probably the best we have.

In terms of iconography, Vaseline is the Campbell’s soup tin, Coke can or Brillo pad box of beauty. Practically everyone owns it, and those who don’t could readily identify its blue-capped jar – and probably list at least five uses for its contents, some of them downright filthy. Robert Augustus Chesebrough, a 22-year-old British chemist, could not have conceived of such success when he invented Vaseline by chance in 1859. He was visiting a Pennsylvania town where petroleum had recently been discovered. He became intrigued by the by-product of the oil-drilling process and observed the oil workers rubbing drill residue into their cuts and burns to heal them. Inspired, he triple-distilled it, cleaning out impurities (Vaseline is still the only petroleum jelly that goes through this process), perfecting the formula over ten years. He then opened a factory in New York and got on his horse and cart to sell his ‘Wonder Jelly’ to the public (mainly by burning himself with acid before an audience, then smearing the wound with it, like some sort of lunatic).

It was a massive success. He renamed it, expanded his distribution, and soon found himself at the helm of a large beauty brand, growing by the month. His petroleum jelly was taken by explorers on the first successful expedition to the North Pole (on account of it not freezing), was made standard issue for US soldiers in the trenches of the First World War, coated special healing gauze for use on the front line during the Second World War, and was stocked in both hospitals and home first-aid kits. A tub of Vaseline is sold every thirty-nine seconds somewhere in the world, and is utilised in a vast petroleum-based product range. Poured into a tin it becomes Vaseline Lip Therapy, the world’s biggest lip brand. Whipped with glycerin into lotion, it becomes Vaseline Intensive Care Lotion, the first port of call for many dry skin sufferers. In beauty alone, it has endless applications. It slicks down unruly brows, adds sheen to cheekbones, mixes with any powder to become coloured gloss, adds shine to legs, removes old glue from false lashes, blends with sugar to act as a lip scrub, diverts self-tan headed for dry spots, and lines cuticles to prevent nail polish migration. It is never missing from photo shoots, where in the past it even greased up camera lenses to give film stars a misty, otherworldly glow.

Читать дальше