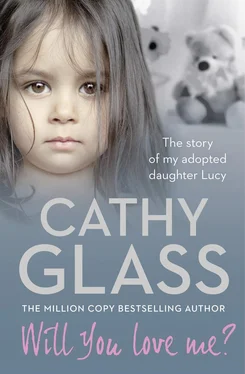

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2013

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2013

Cover layout design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2016

Cover photograph © Urban Zone/Alamy (posed by model)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007530915

Ebook Edition © September 2013 ISBN: 9780007530922

Version: 2018-04-06

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Epigraph

Prologue

PART ONE

Chapter One: Desperate

Chapter Two: Escape

Chapter Three: Concerned

Chapter Four: Too Late to Help

Chapter Five: Family

Chapter Six: Neglect

Chapter Seven: No Chance to Say Goodbye

Chapter Eight: A Good Friend

Chapter Nine: ‘I Hate You All!’

PART TWO

Chapter Ten: ‘A Family of My Own’

Chapter Eleven: Lucy

Chapter Twelve: No Appetite

Chapter Thirteen: ‘Do Our Best’

Chapter Fourteen: Control

Chapter Fifteen: ‘I Don’t Want Her Help!’

Chapter Sixteen: Testing the Boundaries

Chapter Seventeen: Progress

Chapter Eighteen: ‘I’d Rather Have You’

Chapter Nineteen: Happy Holiday

Chapter Twenty: ‘Will You Love Me?’

Chapter Twenty-One: ‘No One Wants Me’

Chapter Twenty-Two: A New Year, a New Social Worker

Chapter Twenty-Three: ‘She’s OK for a Girl’

Chapter Twenty-Four: Special Day

Chapter Twenty-Five: Thunderstorm

Chapter Twenty-Six: ‘I’ll Try My Best’

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Special Love

Cathy Glass

If you loved this book …

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

A big thank-you to my editor, Holly; my literary agent Andrew; and Carole, Vicky, Laura and all the team at HarperCollins.

‘Every time I hear a newborn baby cry …

Then I know why,

I believe.’

‘I Believe’ by Ervin Drake

I heard Pat, Lucy’s carer, knock on Lucy’s bedroom door, and then a slight creak as the door opened, followed by: ‘Your new carer, Cathy, is on the phone for you. Can you come and talk to her?’

There was silence and then I heard the bedroom door close. A few moments later Pat’s voice came on the phone again. ‘I told her, but she’s still refusing to even look at me. She’s just sitting there on the bed staring into space.’

My worries for Lucy rose.

‘What should I do now?’ Pat asked, anxiously. ‘Shall I ask my husband to talk to her?’

‘Does Lucy have a better relationship with him?’ I asked.

‘No, not really,’ Pat said. ‘She won’t speak to him, either. We might have to leave her here until Monday, when her social worker is back at work.’

‘Then Lucy will have the whole weekend to brood over this,’ I said. ‘It will be worse. Let’s try again to get her to the phone. I’m sure it will help if she hears I’m not an ogre.’

Pat gave a little snort of laughter. ‘Jill said you were very good with older children,’ referring to my support social worker.

‘That was sweet of her,’ I said. ‘Now, is your phone fixed or cordless?’

‘Cordless.’

‘Excellent. Take the handset up with you, knock on Lucy’s bedroom door, go in and tell her again I would like to talk to her, please. But this time, leave the phone on her bed facing up, so she can hear me, and then come out. I might end up talking to myself, but I’m used to that.’

Pat gave another snort of nervous laughter. ‘Fingers crossed,’ she said.

I heard Pat’s footsteps going up the stairs again, followed by the knock on Lucy’s bedroom door and the slight creak as it opened. Pat’s voice trembled a little as she said: ‘Cathy’s still on the phone and she’d like to talk to you.’

There was a little muffled sound, presumably as Pat put the phone on Lucy’s bed, and then I heard the bedroom door close. I was alone with Lucy.

Lucy and I believe we were destined to be mother and daughter; it just took us a while to find each other. Lucy was eleven years old when she came to me. I desperately wish it could have been sooner. It breaks my heart when I think of what happened to her, as I’m sure it will break yours. To tell Lucy’s story – our story – properly, we need to go back to when she was a baby, before I knew her. With the help of records we’ve been able to piece together Lucy’s early life, so here is her story, right from the start …

PART ONE

It was dark outside and, at nine o’clock on a February evening in England, bitterly cold. A cruel northeasterly wind whipped around the small parade of downbeat shops: a newsagent’s, a small grocer’s, a bric-a-brac shop selling everything from bags of nails to out-of-date packets of sweets and biscuits, and at the end a launderette. Four shops with flats above forming a dismal end to a rundown street of terraced houses, which had once been part of the council’s regeneration project, until its budget had been cut.

Three of the four shops were in darkness and shuttered against the gangs of marauding yobs who roamed this part of town after dark. But the launderette, although closed to the public, wasn’t shuttered. It was lit, and the machines were working. Fluorescent lighting flickered against a stained grey ceiling as steam from the machines condensed on the windows. The largest window over the dryers ran with rivulets of water that puddled on the sill.

Inside, Bonnie, Lucy’s mother, worked alone. She was in her mid-twenties, thin, and had her fair hair pulled back into a ponytail. She was busy heaving the damp clothes from the washing machines and piling them into the dryers, then reloading the machines. She barely faltered in her work, and the background noise of the machines, clicking through their programmes of washing, rinsing, spinning and drying, provided a rhythm; it was like a well-orchestrated dance. While all the machines were occupied and in mid-cycle, Bonnie went to the ironing board at the end of the room and ironed as many shirts as she could before a machine buzzed to sound the end of its cycle and needed her attention.

Bonnie now stood at the ironing board meticulously pressing the shirts of divorced businessmen who didn’t know how to iron, had no inclination to learn and drove past the launderette from the better end of town on their way to and from work. Usually they gave her a tip, which was just as well, for the money her boss, Ivan, gave her wasn’t enough to keep her and her baby. Nowhere near.

Читать дальше