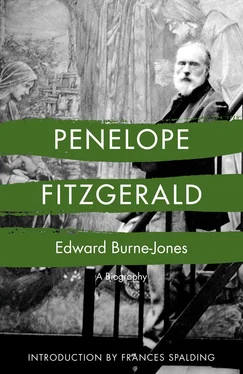

Frances Spalding

2014

Permission to reproduce illustrations has been kindly given by the following: Victoria & Albert Museum for photographs of Mrs Pat Campbell, May Morris, William Morris, Margaret Burne-Jones and Kate Vaughan; Sotheby’s on behalf of a private owner for Georgiana Burne-Jones by Burne-Jones; British Museum for cartoons of Burne-Jones in middle age (from Letters to Katie , by permission of Macmillan London and Basingstoke); London Borough of Hammersmith Public Libraries for photographs of the Burne-Jones and Morris families, Georgiana Burne-Jones by Edward Poynter, Edward Burne-Jones and his son Phil, and Edward Burne-Jones and Angela Mackail; St Cecilia’s Window, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, by kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church Cathedral.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in future editions.

FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Burne-Jones regarded with gloomy distaste the prospect of becoming the subject of a biography. Yet he was a late Romantic, whose pictures, on his own admission, are a series of images scarcely to be understood without a knowledge of the life which projected them. In this book I have tried to trace faithfully the daily life with its successes and disasters which he accepted with a modest irony peculiarly his own, and the inner life of a painter who might have said, with Jung: ‘If I had left these images hidden in my emotions, they might have torn me in pieces.’

Any biographer of Burne-Jones must start from the Memorials collected during the six years after his death by his wife Georgiana, and from the materials for it which she deposited in a tin box in the Fitzwilliam Museum. There are, however, many other sources, particularly for the second part of his career, from 1870 to 1898. Most of the bibliography given at the end of this book consists of contemporary accounts and reminiscences. But beyond these there are diaries, notebooks and work-lists and more than three thousand letters written by Burne-Jones to his friends, who kept them out of affection, even when they were asked to throw them away

My gratitude is due to the following people for their kindness and hospitality, and for generously allowing me to make use of papers in their possession: Miss Mary Chamot, who encouraged me to begin to research, and Professor W.E. Fredeman, who explained to me how to set about it; Mr Oliver Bagot, Mr Francis Cassavetti, Mrs Imogen Dennis, Lord Hardinge of Penshurst, the Dowager Lady Hardinge of Penshurst, Mr George Howard, Mrs Celia Rooke, Mr Lance Thirkell, Lady Tweedsmuir and the Society of Antiquaries of London.

I should also like to thank the following people who have answered enquiries and helped me in many different ways: Mrs Raymond Asquith, Lord Baldwin of Bewdley, Mme Marielle de Baissac, Mr Wilfrid Blunt, Mr Toby Buchan, Dr Raymond Chapman, Mr Charles Carrington, Mr Leslie Cavan, Lord and Lady Clwyd, Mr Norman Colbeck, Dr Malcolm Easton, Professor Leon Edel, Dr Irmgard Feldhaus (Clemens-Sels Museum), Lady Gibson, Miss Phyllis Giles (Fitzwilliam Museum Library), Sir William Gladstone, Professor Gordon Haight, Miss L.F. Hasker (Hammersmith Borough Libraries), Mr Philip Henderson, Miss Helen Henschel, Mr Charles Jerdein, Mr Jeremy Maas, Lady Mander, Professor Roderick Marshall, Mrs June Moll (University of Texas at Austin), Mr David Masson (Brotherton Collection, University of Leeds), Mr Tom Nelson, Mr Peter Norton, Mr Richard Ormond, Mrs Dorothy Parish, Mr Terry Pepper, Mrs Louis Reynolds, Mrs Mary Ryde, Mr A.C. Sewter, Mr E.E.F. Smith (Clapham Antiquarian Society), Mr D.E. Clayton-Stamm, Miss Susie Svoboda, Mr E.F. Thomas (churchwarden of St Margaret’s, Rottingdean), Mr W.S. Taylor, Mr F.H. Thompson (Society of the Antiquaries of London), Mr Raleigh Trevelyan, Mrs Elizabeth Wansbrough, Miss M. Walls (The Grange Museum, Rottingdean). In particular I should like to thank Mr John Christian for his patience and expert knowledge in correcting the typescript; the staff of the Print Rooms of the British Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Watts Galleries, Compton, the William Morris Galleries, Walthamstow; and my own family.

The following publishers have kindly given permission for extracts quoted in the text: George Allen & Unwin (The Winnington Letters edited by Van Akin Burd); Peter Davies Ltd (The Macdonald Sisters by Lord Baldwin, and The Young du Maurier edited by Daphne du Maurier); the Yale University Press (The Letters of George Eliot edited by Gordon S. Haight).

P.M.F.

1 1833–53

A CHILDHOOD WITHOUT BEAUTY

Edward Burne-Jones was born on 28 August 1833, as Edward Coley Burne Jones, the only surviving child of Edward Richard Jones. He never knew his sister, who died in infancy, nor his mother, who died a few days after his birth, but he felt all through his life that he had lost them and sorely missed them.

Mr Jones was a not even moderately successful Birmingham gilder and frame-maker. He was probably of Welsh descent, but his ancestry is lost among many Joneses; as Burne-Jones pointed out when he at last took the step of hyphenating his name; to be called Jones is to ‘face annihilation’. He did not know the Christian names of his grandparents on either side: his mother might have been more likely to keep the family annals, but she was dead.

The widower and his pale, delicate, unassertive little son continued to live over the shop, sharing a small bedroom overlooking the timber-yard behind it, where the raw wood for the frames was kept. Every Sunday, after listening to an Evangelical sermon with other small tradesmen at St Mary’s, Whitall Street, they went to visit Mrs Jones’s grave, and Ned was frightened to see his father cry. ‘There’s one thing I owe to my father, that is his sense of pathos. Oh, what a sad little home ours was and how I used to be glad to get away from it.’ 1Half-holidays also meant a visit to the churchyard where Mr Jones sometimes gripped his head so hard that he cried out with pain. This kind of commemoration did not strike him, then or afterwards, as strange. He only pointed out that, had he guessed then what adult life was like, he wouldn’t have passed his childhood in such a ‘needlessly saddish manner’. 2His clothes were made out of what was left over from his father’s suits, every penny was saved, and Mr Jones, putting in long hours in the workshop, tiptoed up to bed so as not to wake the child. In an age of self-help, this father could show thrift and sobriety, but not confidence. His failure in business was the result of unworldliness and inefficiency in the craft itself; as a hard worker, he set an excellent example.

Housekeeping for the disconsolate family was undertaken by a Miss Sampson, described by Lady Burne-Jones as ‘uneducated, with strong feelings and instincts’. Ned recalled being sometimes given a penny and spending it on a ‘mutton-pie, sodden with rancid fat’ 3as a relief from her cooking. It was Miss Sampson who told him, when he was building a child’s city of small stones, that ‘you must not call it Jerusalem, Edward’; she acted as a represser of fantasy, useful to a child whose imagination is strong enough to thrive on opposition and to become – as Burne-Jones pointed out – ‘his private torment’. Ways had to be devised early on to avoid telling Miss Sampson what he was thinking about, so that it could remain to trouble him. He suffered for as long as he could remember from bad dreams, and from waking to find ‘large anxious faces of grown-ups’ bending over him. It was his habit as an artist to speak of his dream world, where real and unreal mixed without priority, as if it were his own retreat, but in fact he never seriously entered it without apprehension.

Читать дальше