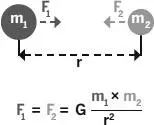

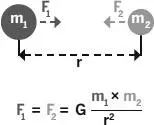

The end of the revolution started by Copernicus around 1510, and the beginning of modern mathematical physics, can be dated to 5 July 1687, when Isaac Newton published the Principia . He demonstrated that the Earth-centred Ptolemaic jumble can be replaced by a Sun-centred solar system and a law of universal gravitation, which applies to all objects in the universe and can be expressed in a single mathematical equation:

The equation says that the gravitational force between two objects – a planet and a star, say – of masses m 1and m 2can be calculated by multiplying the masses together, dividing by the square of the distance r between them, and multiplying by G , which encodes the strength of the gravitational force itself. G , which is known as Newton’s Constant, is, as far as we know, a fundamental property of our universe – it is a single number which is the same everywhere and has remained so for all time. Henry Cavendish first measured G in a famous experiment in 1798, in which he managed (indirectly) to measure the gravitational force between lead balls of known mass using a torsion balance. This is yet another example of the central idea of modern physics – lead balls obey the same laws of nature as stars and planets. For the record, the current best measurement of G = 6.67 × 10 -11N m 2/kg 2, which tells you that the gravitational force between two balls of mass 1kg each, 1 metre apart, is just less than ten thousand millionths of a Newton. Gravity is a very weak force indeed, and this is why its strength was not measured until 71 years after Newton’s death.

NEWTON’S LAW OF GRAVITY

F

Force between the masses

G

Gravitational constant

m 1

First mass

m 2

Second mass

r

Distance between the centres of the masses

This is a quite brilliant simplification, and perhaps more importantly, the pivotal discovery of the deep relationship between mathematics and nature which underpins the success of science, described so eloquently by the philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell: ‘Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty – a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show. The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as in poetry.’

Nowhere is this sentiment made more clearly manifest than in Newton’s Law of Gravitation. Given the position and velocity of the planets at a single moment, the geometry of the solar system at any time millions of years into the future can be calculated. Compare that economy – you could write all the necessary information on the back of an envelope – with Ptolemy’s whirling offset epicycles. Physicists greatly prize such economy; if a large array of complex phenomena can be described by a simple law or equation, this usually implies that we are on the right track.

The quest for elegance and economy in the description of nature guides theoretical physicists to this day, and will form a central part of our story as we trace the development of modern cosmology. Seen in this light, Copernicus assumes even greater historical importance. Not only did he catalyse the destruction of the Earth-centred cosmos, but he inspired Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, Newton and many others towards the development of modern mathematical physics – which is not only remarkably successful in its description of the universe, but was also necessary for the emergence of our modern technological civilisation. Take note, politicians, economists and science policy advisors of the twenty-first century: a prerequisite for the creation of the intellectual edifice upon which your spreadsheets, air-conditioned offices and mobile phones rest was the curiosity-driven quest to understand the motions of the planets and the Earth’s place amongst the stars.

AT THE CENTRE OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM

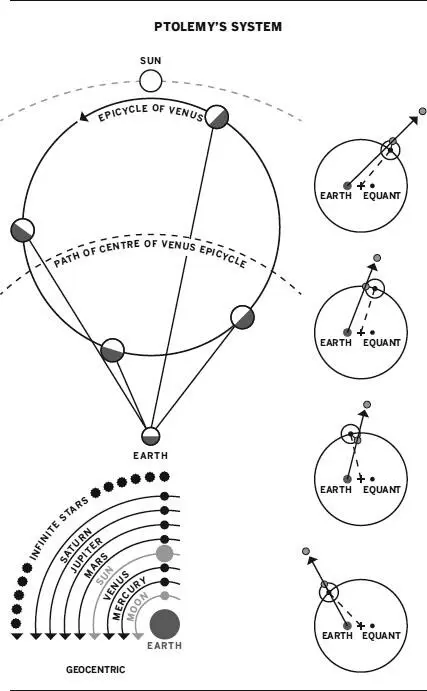

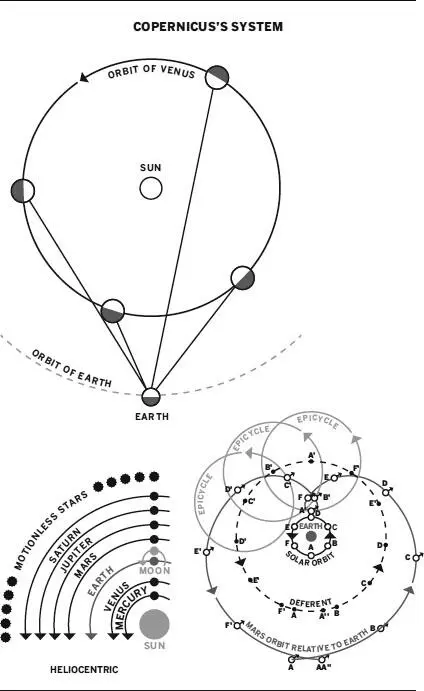

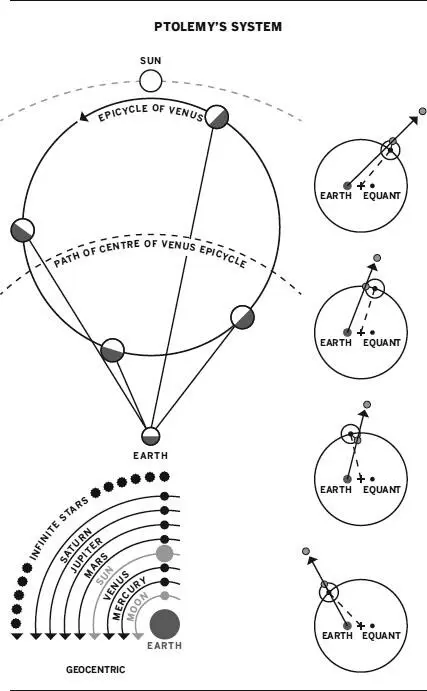

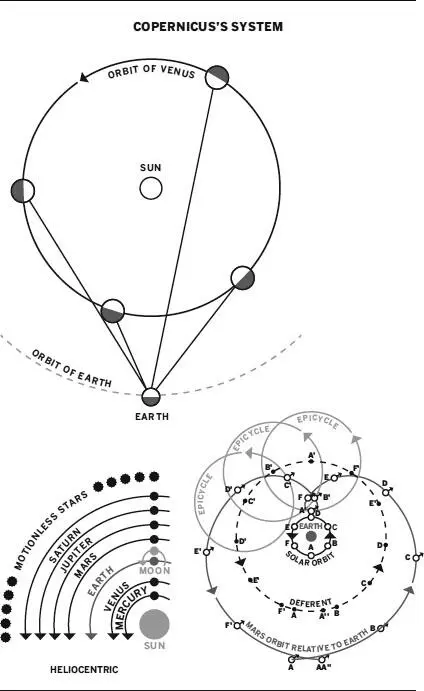

Matching the observations of the wandering stars – the planets – of the night sky with the idea that the Earth was at the centre of the solar system required extremely complex models. In the case of Venus, combining the Earth at the centre with the observations meant that Venus had a circular orbit around a point midway between the Earth and the Sun, so-called epicycles, with all the other planets having similar complicated orbits around various points scattered around the solar system. Placing the Sun at the centre of the solar system, with the planets arranged in their familiar order, with the Moon orbiting the Earth, gave a much simpler system.

CHANGING PERSPECTIVE Changing Perspective Outwards to the Milky Way Searching for Patterns in Starlight Beyond the Milky Way The Great Debate The Political Ramifications of Reality, or ‘How to Avoid Getting Locked Up’ The Happiest Thought of My Life A Day Without Yesterday Are We Alone? Science Fact or Fiction? The First Aliens Listen Very Carefully The Golden Voyage Alien Worlds The Recipe for Life Origins A Brief History of Life on Earth A Briefest Moment in Time So, are We Alone? Who are We? Spaceman Apeman Lucy in the Sky From the North Star to the Stars Climate Change in the Rift Valley and Human Evolution ‘An Unprecedented Duel with Nature’ Farming: The Bedrock of Civilisation The Kazak Adventure: Part 1 Intermission: Beyond Memory The Kazak Adventure: Part 2 Why are We Here? A Neat Piece of Logic New Dawn Fades The Rules of the Game Nature’s Fingerprint A Brief History of the Snowflake How the Leopard Got Its Spots A Universe Made for Us? A Day Without Yesterday? What is Our Future? Making the Darkness Visible Sudden Impact Seeing the Future Science Vs. Magic The Wonder of It All Dreamers: Part 1 Dreamers: Part 2 The End Plate Section Credits Picture Section Footnotes Index Acknowledgements About the Authors About the Publisher

1968 was a difficult year on planet Earth. The Vietnam War, the bloodiest of Cold War proxy tussles, was at its height, ultimately claiming over three million lives. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, prompting presidential hopeful Bobby Kennedy to ask the people of the United States ‘to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world’. Kennedy himself was assassinated before the year was out. Elsewhere, Russian tanks rolled into Prague, and France teetered on the edge of revolution. As I approached my first Christmas, my parents could have been forgiven for wondering what kind of world their son would inhabit in 1969. And then, as Christmas Eve drifted into Christmas morning, an unexpected snowfall decorated Oakbank Avenue and Borman, Lovell and Anders, 400,000 kilometres away, saved 1968.

Apollo 8 was, in the eyes of many, the Moon mission that had the most profound historical impact. It was a terrific, noble risk; a magnificent roll of the dice; a distillation of all that is great about exploration; a tribute to the sheer balls of the astronauts and engineers who decided that, come what may, they would honour President Kennedy’s pledge to send ‘a giant rocket more than 300 feet tall, the length of this football field, made of new metal alloys, some of which have not yet been invented, capable of standing heat and stresses several times more than have ever been experienced, fitted together with a precision better than the finest watch, carrying all the equipment needed for propulsion, guidance, control, communications, food and survival, on an untried mission, to an unknown celestial body, and then return it safely to Earth, re-entering the atmosphere at speeds of over 40,000 kilometres per hour, causing heat about half that of the temperature of the Sun – almost as hot as it is here today – and do all this, and do it right, and do it first before this decade is out’. If I heard that from a leader today I’d be first on the rocket. Instead I have to listen to vacuous diatribes about ‘fairness’, ‘hard-working families’, and how ‘we’re all in it together’. Sod that, I want to go to Mars.

Читать дальше