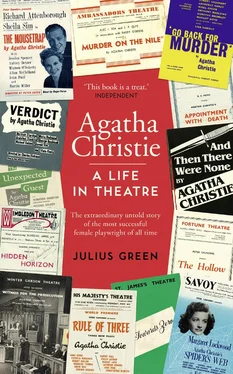

Christie was passionate about theatre and was deeply involved in the processes of making it. She attended and contributed to rehearsals, and her delightful ‘author’s notes’ at the front of some of the published editions of the plays show her engaging with everything from the mechanics of creating the effect of a lift ascending and descending in Appointment with Death to the problems associated with the unusually large dramatis personae of Witness for the Prosecution and the ‘ageing’ of actors and multiple locations in Go Back for Murder . She was very aware of the practicalities of putting on a play, favouring single sets and relatively small casts ( Appointment with Death and Witness for the Prosecution are notable exceptions), and this partly accounts for her enduring popularity with cash-strapped repertory theatres and touring companies over the years, and the consequent law of diminishing returns in terms of both production values and credibility within the theatre community.

Born in 1890, for the first ten years of her life Agatha was a Victorian; Gladstone became Prime Minister for the fourth time shortly before her first birthday. As a teenager and a young woman she was an Edwardian. She waved husbands off to both world wars, and women got the vote on the same basis as men when she was thirty-eight. In 1969 she watched man land on the moon on television, and when she died in 1976, Harold Wilson was Prime Minister. Her first success as a novelist came when she was thirty; but although she started writing plays as a teenager, none of her work was staged until she was forty, and her playwriting career didn’t really take off until she was in her sixties. This is an interesting inversion of the timeline of Noël Coward’s career; Coward and Christie were contemporaries, but his success as a playwright came much earlier in life and reached its pinnacle in the Second World War with Blithe Spirit and Present Laughter , just as Christie was experiencing her first West End hit with Ten Little Niggers . (The history of this play’s problematic title is examined later in this book.)

All but one of Christie’s plays are firmly set in the period in which they were written, and they resist any attempt at updating in just the same way that the work of Noël Coward does. Although the moral dilemmas faced by the characters and their guilt, obsession, love and jealousy are timeless, their behaviour and interactions are very much a function of the social mores of the time in which each play is set; not to mention the fact that modern communications technology would severely compromise key elements of the plotting. The stakes are raised in several of the storylines by the ever-present threat of the hangman’s noose; particularly in Verdict , where the existence of the death penalty clearly informs the protagonist’s decision not to turn the murderer over to the police, and in Towards Zero , where it accounts for an extraordinary plot twist. The acceptability of smoking provides a continuous subtext of cigarettes, pipes and cigars both as a form of social interaction (offering someone a cigarette can be as good as a chat-up line) and to underscore key moments of tension. A nervous character will reach for a cigarette and a pipe smoker is usually to be trusted.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the society reflected in the majority of Christie’s stage work is a halcyon one of pre-war vicarage tea parties. Ironically, this relatively elderly woman, whose upbringing was defined by the mores of the previous century and whose frame of reference is generally assumed to be that of the pre-war era, found lasting fame as a playwright in the decade when ‘angry young men’ were allegedly redefining the theatrical playing field at the Royal Court. Christie did not live a cocooned middle-class life. She was adventurous, widely travelled and politically aware, and encountered people of all classes and cultures. She worked in a hospital dispensary during the First World War (gaining a comprehensive knowledge of poisons in the process), was one of the first people to surf standing up on a surfboard (whilst visiting South Africa) and made use of recent changes in the law to divorce her cheating first husband, Archie Christie, in 1928. Her work spans a century of massive social and political change and this does not go unacknowledged within it, from The Hollow with its crumbling aristocracy facing up to the loss of empire to the overtly political challenge to the conservative orthodoxy represented by Alderman Higgs in Appointment with Death , the ‘not a Red, just pale pink’ Miss Casewell in The Mousetrap , the post-war suspicion of foreigners in Witness for the Prosecution and the persecuted East European immigrants at the centre of Verdict .

Whilst the received wisdom is that Christie’s novels are to a certain extent formulaic, and much scholarly time has been devoted to analysing these alleged formulae, the same most definitely cannot be said of her work as a playwright, and it almost seems that she found herself enjoying greater freedom of expression as a writer in this genre. A repertoire encompassing the edge-of-your-seat chiller Ten Little Niggers , the definitive courtroom drama Witness for the Prosecution , the Rattiganesque psychological drama Verdict and the ‘time play’ Go Back for Murder can hardly be described as formulaic and there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ Agatha Christie play. Despite the enduring perception of her work as little more than an extended game of Cluedo, Christie’s plays tend to be character-led rather than plot-led, and she clearly relishes entrusting the entire momentum of the story-telling to the voices of her ever-colourful dramatis personae. Her dialogue fairly trips off the tongue and is spiced with witticisms and observational comedy frequently worthy of Wilde. In her plays the detectives and police inspectors are usually relegated to minor roles, with the solving of a crime taking second place to the human drama that is being played out. It is as if we come closer to what Christie wants to say as a writer without the dominating presence of Poirot and Marple. With the exception of Poirot’s appearance in Black Coffee , the first play of hers to be produced (in 1930), neither character features in any of her own stage plays, and indeed she removed Poirot from the storyline when undertaking her own adaptations of four of the novels in which he appears, maintaining, doubtless correctly, that he would pull focus on stage.

Explorations of guilt, revenge and justice loom large in Christie’s stage work and are timeless subjects that go back to the very dawn of playwriting, but although the concept of justice and the many forms that it can take is central to many of her plays, the image of the policeman leading away the guilty party in handcuffs is rarely part of her theatrical vocabulary. An inability to escape the past is a recurring theme, and man’s infidelity is often the catalyst for its exploration, a frequently used storyline that some have attributed to the philandering of Christie’s own first husband. In Christie’s work for the stage, the murder itself is usually nothing more than a plot device to move forward the action and to set the scene for Christie’s exploration of the human condition and the dilemmas faced by her characters. ‘Who’ dunit is far less important than ‘Why’.

Agatha was a regular theatregoer from childhood and engaged in theatrical projects from an early age, was hugely theatrically literate and drew on a broad frame of reference from Grand Guignol to Whitehall farce, all of which can be seen in her work. But her lifelong passion was for Shakespeare, and her theatrical vocabulary was defined in particular by an enjoyment and understanding of his works, gained as an audience member and a reader rather than a scholar. In a 1973 letter to The Times she wrote: ‘I have gone to plays from an early age and am a great believer that that is the way one should approach Shakespeare. He wrote to entertain and he wrote for playgoers.’ 7And in her autobiography she says,

Читать дальше