At eight years old I was sent to a small boarding school miles away in the countryside near Salisbury. For the first few terms I was poleaxed by homesickness, but after a while I lightened up, and then suddenly – for the only time in my life – school became a complete delight. We wore cool navy-blue boiler suits when we went outside to play, and there was an old quarry in the vast school grounds, and hardly any girls to be scared of. I was extremely lucky to be there; my parents had had to borrow money to send me in the first place, and slowly I began to repay some of their investment. I developed a random obsession with Austria and, aged nine, began a James Bond style novel, casting myself as the heroic Austrian protagonist. I supported Austria passionately at football and in the skiing on television on Sundays, and had an Austrian flag on my bedroom wall. No-one knew what had triggered this Austrian obsession, not even me; I’d never even visited it.

During my school holidays back in Winchester I made friends with my next-door neighbour. Alexander was a spoilt only child, which meant he could get hold of almost anything. We liked playing toy soldiers, sci-fi laser war and Lego – he had so much Lego he had to keep it in buckets and giant Tupperware boxes, and his armies were so huge that wherever you walked in his house your feet would get spiked by the piles of discarded military enmeshed in the carpet. We also liked ABBA and spent many evenings dancing chaotically in Alex’s front room. We even made ABBA compilation tapes, for no better reason than Alex’s posh stereo had twin tape decks. And, for a while, that was all we knew about music.

AC/DC changed all that. First chance I got, I rushed over to Alex’s to tell him about my discovery. He went straight downstairs to request an AC/DC album from his parents, and a day later he was the proud owner of their 1979 masterpiece Highway to Hell . I was so jealous I refused to listen to it, but I couldn’t keep this up for long. As we cued-up the record for the fiftieth time, I realised that this wasn’t just a passing phase – this was the real deal, the meaning of life . There were rampant phalanxes of guitars, drumming so hefty it felt like dinosaurs were stomping round the room, and a voice so astringent it could strip paint off the walls. Alex said he was going to change his name to Alexander AC/DC and that his parents had said it was OK, and I, temporarily, believed him.

Together Alex and I learned that AC/DC had had two different singers: Bon Scott, who sang like a snake and was dead (he choked on his own sick in 1980), and his replacement Brian Johnson, who wore a flat cap and a vest and sounded like a vomiting pensioner (maybe that’s what had pissed Granny off so much). Alex and I liked Bon the best – too much Brian all in one go was distressing, and Bon sounded sexy, though we didn’t know what ‘sexy’ was exactly. We just knew Bon was cooler, and funnier, and being dead we knew he couldn’t turn around and decide to write a ballad.

Bon was great, but our favourite thing about AC/DC was their iconic lead guitarist, Angus Young. Angus was a short Australian man with straggly hair who always wore a school uniform: velvet shorts, velvet jacket, velvet cap, shirt and tie. It wasn’t the fact that he dressed like us that impressed us particularly – although we respected the gimmick – it was the sheer feral noise he made with his guitar. Every note that Angus played seemed to possess a kind of taut, evil shiver; it got us right in the diaphragm. His perpetually blazing Gibson transfixed us and we devoutly mewed every note in exhausting bouts of keep-up air guitar in Alex’s bedroom. While the rest of the DC stood rooted to the spot in their tight mucky T-shirts under their curtains of hair, Angus duck-walked his way around the stage like a depraved goblin Chuck Berry, dripping rivers of sweat behind him as he methodically, ritually disrobed. We duck-walked with our air guitars around Alex’s room, careful not to skip the needle.

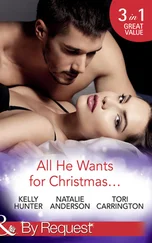

Me as Angus at my sister’s fancy-dress birthday party. L – R: dog, sister, me.

A month later, Alex’s parents took us to Le Havre for a weekend. They were both doctors and were travelling over there for a medical conference. Alex and I spent hours locked in the hotel room, squinting out over the docks, watching sea-gulls attacking cars. When we were eventually let loose in a giant department store called Les Printemps, Alex was allowed two new AC/DC albums and I was allowed one. It took us hours to choose. In the end I went for Powerage while Alex demanded Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap and If You Want Blood, You Got It (I still feel estranged from both to this day). Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap featured songs called ‘Big Balls’, ‘Love at First Feel’ and ‘Squealer’. It was getting harder to avoid the sexual connotations.

We were banned from listening to the tapes back at the hotel or during the journey home, which was probably a good thing anyway with all that talk of big balls. So instead we bickered over whose tape was better before we’d even heard them, and learned the track listings and the times of the songs and every detail from the covers. My tape had a picture of Angus with a crazed, electrocuted expression on his face and wires coming out of his sleeves instead of hands, which I soon discovered was exactly how he sounded inside. But Alex and and I were worried: had Angus really impaled himself upon his Gibson SG on the front of If You Want Blood, You Got It? It looked extremely convincing. How had he survived that?

Angus – dead?

Back in Winchester, we bought up the DC back catalogue using Alex’s parents’ money and waited impatiently for their first new album since we’d discovered them. It was called Flick of the Switch and had an exciting though minimalist cover, with Angus and his guitar hanging off a giant switch. My favourite song was ‘Bedlam in Belgium’. I imagined the devastation the DC could cause in Belgium – Angus duck-walking down a blazing street that looked a bit like Le Havre, but bigger and engulfed in flames. Unfortunately for us, Flick of the Switch was their worst album to date, but we hadn’t discovered the music press yet, so it took a few years to realise.

My family’s appetite for AC/DC hadn’t progressed at quite the speed I’d initially expected. I was particularly let down by my father’s response, who, as a brilliant pianist, bass player and all-round musical Svengali to our family (when he felt like it), should have been the most appreciative. He became agitated when I played the DC on his fragile and expensive record player at objectionable volume while the family sat watching The Two Ronnies . He wasn’t completely anti-pop – he owned ‘Strawberry Fields’/ ’Penny Lane’, a T-Rex album, and a Chris Squire (out of Yes) solo album that someone had once given him by mistake. But whenever he heard the DC he would wrinkle up his face comically and hold his ears as Brian Johnson screeched out ‘What Do You Do for Money, Honey’ and ‘Let Me Put My Love Into You’ and ‘Givin’ the Dog a Bone’. I convinced myself that if he listened long and hard enough he’d eventually get it, just as I had. I said, ‘OK, maybe that one wasn’t so good, perhaps not the best, I agree, but hold on, listen to this one.’ And he’d light another Silk Cut and turn up the darts on the television and I would translate an annoyed movement of his mouth into acquiescence.

Читать дальше