For Flora and Izzy

Contents

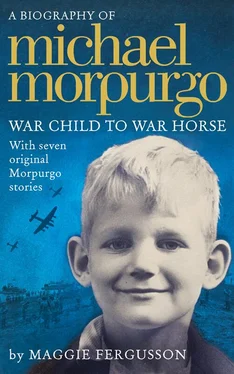

Cover

Title Page

Dedication For Flora and Izzy

Preface by Michael Morpurgo Preface For me the telling of stories has been my way of communicating with everyone around me. Each of us sees the world differently from anyone else, has our own perspective on who we are, who we have been, and what kind of a world it is that we find ourselves living in. We have our own views on what influences, which individuals, what happenings, have made us who we are. Most writers use memory, to a greater or lesser extent, as a stimulus for their stories or poems, but I think I probably have relied on it more than most. Maybe it’s because I have a less fertile imagination, and have always needed that bedrock of memory on which to construct my stories. But memory is not that reliable, is always biased – after all memory is simply your own life remembered from your own point of view – and not necessarily then a reliable source, if truth be told! That doesn’t matter of course if you’re writing fiction, but, when trying to discover the truth about yourself, it’s important not to confuse it with fiction. All my writing life I have confused the two, which is why I knew I would find it almost impossible to tell my own story without straying into fiction, either unintentionally or intentionally. So, when it was suggested I write my own memoir, I knew I couldn’t and probably shouldn’t do it. I knew I would have to find someone who could tell the story of that life objectively, critically and with integrity. I had read Maggie Fergusson’s biography of the Scottish poet George Mackay Brown, and found it compelling and deeply moving. So I asked her if she might like to write my life story, and do it her way, the story of a story maker. And that is what she has done wonderfully well. I learnt much about life from this book, long forgotten memories, distorted memories. It is like looking into a mirror – not that comfortable an experience, particularly as you get older. The mistakes and the fault lines are there in every wrinkle, but so is the living. We wanted it, though, not to be simply a straight biography, but to weave into it fictional stories that reflect my life as it was lived. Shakespeare it was who suggested we have ‘seven ages’ in our lives. So tell the biography in seven chapters, we thought, alongside a story inspired by each ‘age’ of my life. It seemed to us that the fact might illuminate the fiction and vice versa, a fusion from which both might benefit. Michael Morpurgo Devon, 2013

1. Where to Begin?

‘Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble’

2. Spotless Officer Number One

‘A Fine Night, and All’s Well’

3. Situation Critical

‘Littleton 12–Wickhamstead 0’

4. A Winning Formula

‘Didn’t We Have a Lovely Time?’

5. The Heat o’ the Sun

‘A Bit of a Daredevil’

6. Better Answer – Might Be Spielberg

‘The Saga of Ragnar Erikson’

7. Still Seeking

‘Snug’

Activities

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

For me the telling of stories has been my way of communicating with everyone around me. Each of us sees the world differently from anyone else, has our own perspective on who we are, who we have been, and what kind of a world it is that we find ourselves living in. We have our own views on what influences, which individuals, what happenings, have made us who we are.

Most writers use memory, to a greater or lesser extent, as a stimulus for their stories or poems, but I think I probably have relied on it more than most. Maybe it’s because I have a less fertile imagination, and have always needed that bedrock of memory on which to construct my stories. But memory is not that reliable, is always biased – after all memory is simply your own life remembered from your own point of view – and not necessarily then a reliable source, if truth be told! That doesn’t matter of course if you’re writing fiction, but, when trying to discover the truth about yourself, it’s important not to confuse it with fiction.

All my writing life I have confused the two, which is why I knew I would find it almost impossible to tell my own story without straying into fiction, either unintentionally or intentionally. So, when it was suggested I write my own memoir, I knew I couldn’t and probably shouldn’t do it. I knew I would have to find someone who could tell the story of that life objectively, critically and with integrity. I had read Maggie Fergusson’s biography of the Scottish poet George Mackay Brown, and found it compelling and deeply moving. So I asked her if she might like to write my life story, and do it her way, the story of a story maker. And that is what she has done wonderfully well. I learnt much about life from this book, long forgotten memories, distorted memories. It is like looking into a mirror – not that comfortable an experience, particularly as you get older. The mistakes and the fault lines are there in every wrinkle, but so is the living.

We wanted it, though, not to be simply a straight biography, but to weave into it fictional stories that reflect my life as it was lived. Shakespeare it was who suggested we have ‘seven ages’ in our lives. So tell the biography in seven chapters, we thought, alongside a story inspired by each ‘age’ of my life. It seemed to us that the fact might illuminate the fiction and vice versa, a fusion from which both might benefit.

Michael Morpurgo

Devon, 2013

Where to begin, when telling the story of a writer’s life?

Perhaps simply with the moment of his birth. Michael Morpurgo, then, was born on 5 October 1943, at the height of the Second World War.

On the morning of his birth The Times announced that Corsica had fallen to the French Resistance – the first department of France to be liberated. In the days that followed it became clear that the Allies had the Germans on the run. On 7 October the Red Army mounted a new thrust on enemy positions along the River Dnieper, breaking the Germans’ 1,300-mile defence front; a week later Italy declared war on Germany. By the end of the month the Allies were bombing the Reich from Italian soil. In early December the British government announced that there would only be enough turkeys for one in ten families at Christmas, but any sense of joylessness was eased, on Boxing Day, by the news that the British navy had sunk the last of the great German battleships, the Scharnhorst , off the coast of Norway.

War has been a constant presence in Michael’s stories. And it is significant, as you will see in the story Michael has written to end this section of the book, that he was a child at a time when the war was just over, yet when its influence was still keenly felt and seen.

But if you want to understand the threads of Michael’s work – the ingredients that combined to make him a storyteller and performer – you need to start earlier, with his family. You see, Michael comes from theatrical roots, something which won’t surprise anyone who has seen him talk about his books on stage. For generations, theatre and stories have been part of the fabric of his family’s life.

Читать дальше