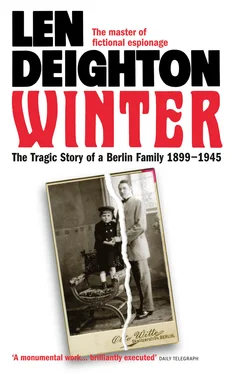

Winter was a biography of the Germany I had come to know over the years. We had lived in Vienna and in an Austrian village near Salzburg, which was now not all that far away, and my sons spoke a strongly accented German. For many Germans, and many historians too, Germany and Austria do not have a separate existence. AJP Taylor, who taught me so much about German history, persuaded me to consider both in unison and for that reason the story of Winter begins in Vienna. One of our neighbours in Riederau village had a son writing for a newspaper in Vienna. At my request, he rummaged through the archives to find out what the weather was like in Vienna on ‘the final evening of the 1800s’. Now I had no excuse for delay.

I knew what I wanted to say; I had been planning it for years. My hesitation had come from the problems of continuity. In the beneficial absence of formal instruction in the skills of writing fiction, I found it natural to write sequences in ‘real time’. In my book conversations and physical actions as depicted were apt to take about the same time as the reader took in reading about them. Of course there were expansions and compressions so that only the highlights of dinner party chit-chat were necessary; split-second reactions were expanded to encompass thought and reactions. But now I was going to relate the events of fifty years; I faced many problems I never even guessed about. Somerset Maugham, a writer I much admired, would often write in the first person of a man who observed the events of which he wrote. Maugham’s voice was apt to bridge his narrative with ‘…it was three years before I was to see either of them again, and it was in very different circumstances’. As a reader I rather delighted in this voyeur writer but I didn’t feel confident enough to use such leaps in time. And the frantic pace of German history would not survive a leisurely survey.

I sought advice from my literary agents Jonathan and Ann Clowes – the most widely read friends I have – and examined several family saga novels, old; and new. There was a lot to learn. More than once I decided to abandon my project but while I was sorting and sifting my research notes the solution became evident. I would eliminate connective material. My chapters would be brief human interactions, like flashes of lightning illuminating long nights of darkness. This format would require careful selection of material so that each chapter provided a vital link in the story. And yet Winter must not be a history book; it had to be an interesting and emotive story of a family living through Europe’s nightmare past.

I returned to Vienna. Vienna is a town different to any other that I know. The small central area is defined by the Ringstrasse around which, according to his son, the amazing Sigmund Freud ‘marched at a terrific speed almost every day’. Vienna is not so much a town as a spectacle: if you don’t want to visit Sankt Marxer Friedhof – where Mozart’s corpse was tossed into a common grave – you can chew on the famous chocolates that bear his name. If you don’t like the music of Mahler, what about Franz Lehar? If Klimt is too opulent, what about Schiele? If you don’t like the Hotel Sacher; savour your Sachertorte in Demels. If you don’t fancy Graham Greene’s sewers; seek Harry Lime on the big wheel in the Prater. Vienna has something for everyone; from the Wiener Werkstätte to the Wienerwald. Within the Ringstrasse there are more churches, historic buildings, restaurants and shops than anyone needs. But the greatest wonders of the city are its magnificent old cafes. So you can see why, for anyone inflicted with insatiable curiosity, or easily diverted, Vienna is no place to write books.

I chose Munich because that city uniquely links Vienna with Berlin. The inhabitants of these three great German cities view each other with dispassionate superiority. While the mighty Austria-Hungary Empire dominated Europe, Vienna ruled. It was Bismarck, and the Prussian armies that in 1870 marched into Paris, that displaced Vienna and established Berlin’s ascendancy. At the turn of the century, Berlin’s music hall comics got guaranteed laughs from jokes that depicted Bavarians and the Viennese as hopeless country bumpkins. But Hitler changed all that. Hitler was an Austrian and his Nazi Party was born in Munich and when Hitler named that town as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung – ‘capital of the movement’ – all jokes about its citizens were hushed.

I visited all three cities frequently while working on this book but Munich was the place where it all began. My sons attended a local boarding school at Schondorf, and put their Austrian accents on the shelf. With the aid of my wife, I interrogated anyone old enough to provide me with memories of the old days. I was listening to the recollections of a fellow customer in a stationery shop when I spotted a small grey ‘typewriter’ that turned out to be Hewlett Packard’s radical new product. It was the world’s first laptop: a unique, strange and awkward beast by today’s standards – and started writing.

Len Deighton, 2010

Nuremberg 1945

Winter entered the prison cell unprepared for the change that the short period of imprisonment had brought to his friend. The prisoner was fifty-two years old and looked at least sixty. His hair had been thinning for years, but suddenly he’d become a bald-headed old man. He was sitting on the iron frame bed, sallow and shrunken. His elbows were resting on his knees and one hand was propped under his unshaven chin. The prison authorities had taken from him his belt, his braces, and his necktie, and the expensive custom-made suit from Berlin’s most famous tailor was now stained and baggy. And yet the dark-underlined eyes were the same, and the pointed cleft chin made him immediately recognizable as a celebrity of the Third Reich, one of Hitler’s most reliable associates.

‘You sent for me, Herr Reichsminister?’

The prisoner looked up. ‘The Reich is kaputt, Germany is kaputt, and I’m not a minister: I’m just a number.’ Winter could think of no way to respond to the bitter old man. He’d become used to seeing him sitting behind the magnificent hand-carved desk in the tapestry-hung room in the ministry, surrounded by aides, secretaries, and assistants. ‘Yes, I sent for you, Winter. Sit down.’

He sat down. So it was all to be formal.

‘I sent for you, Herr Doktor Winter, and I’ll tell you why. They told me you were in prison in London awaiting interrogation. They said that any of us on trial here could choose any German national we wanted for our defence counsel, and that if the one we chose was being held in prison they’d release him to do it. It seemed to me that a man in prison might know what it’s like for me in here.’

Winter wondered if he should offer the ex-Reichsminister a cigarette, but when – still undecided – he produced his precious cigarettes, the military policeman in the corridor shouted through the open door, ‘No smoking, buddy!’

The ex-Reichsminister gave no sign of having heard the prison guard’s voice. He carried on with his explanation. ‘Two, you speak American …speak it fluently. Three, you’re a damned good lawyer, as I know from working with you for many years. Four, and this is the most important, you are an Obersturmbannführer in the SS…’ He saw Winter’s face change and said, ‘Is there something wrong, Winter?’

Winter leaned forward; it was a gesture of confidentiality and commitment. ‘At this very moment, just a few hundred yards from here, there are a hundred or more American lawyers drafting the prosecution’s case for declaring the SS an illegal organization. Such a verdict would mean prison, and perhaps death sentences, for everyone who was ever a member.’

Читать дальше