Elsewhere in the lorry I can hear my mates chatting. It’s just the usual army banter. They’re saying nothing of any great importance. Why would they? They don’t realize what is about to happen. None of us does.

There are only eight of us in the truck. There might have been more, but we’re laden down with boxes of ammo. Sometimes you have to be grateful for small mercies. If there had been more of us, the carnage that lies ahead would have been all the greater.

I look out of the vehicle and smile to myself. I’m just a young man, a kid from the Midlands, but already I’m seeing the world. Having an adventure. Doing what I’ve wanted to do ever since I was a child. And it’s picturesque here. Breathtaking. The kind of place that tourists come to from far and wide to take the air and recharge their batteries. A famous beauty spot. But it’s about to become famous for a very different reason.

On the left-hand side of the truck is a stretch of water, a wide estuary that separates Northern Ireland from the Republic. And, on the other side of the water, thick forest coming down to the shore. It’s impossible for any of us to know what dangers those trees are hiding. Why would we even think about it? They are far away, and in any case we are members of the Parachute Regiment. We’ve passed one of the most rigorous selection procedures in the British Army. We are young and fit, well prepared and confident. Why should we fear what may be lurking in the woods?

The lorry trundles on. The lads continue to chat.

I continue to look out of the lorry, killing time till we reach our destination, little knowing that, for so many of my friends, time is coming to an end.

The worst horrors come without warning. The most brutal shocks are those for which you are the least prepared. And although, deep down, I know what the reality of conflict is, nothing could have prepared me for what is about to happen.

We drive past a trailer parked in a lay-by and filled with bales of hay. I do not notice it because there’s nothing to notice. It’s an ordinary scene. An innocent one.

And I do not hear the bang, nor the screams that follow. I do not smell the stench of burning flesh, or witness the confusion. All I know is darkness.

It’s as though a curtain has been drawn. A curtain that signals the end of my old life, and the beginning of a new one, though what this new life will be like, nobody can say.

It is a darkness that means the lights of many lives have been extinguished. And that my own world can never be the same again.

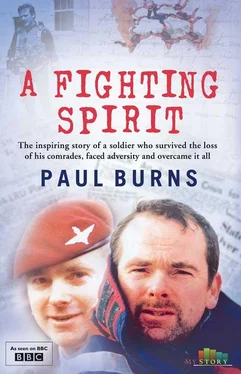

Chapter One The Terror of Toton Contents Cover Title Page PAUL BURNS A FIGHTING SPIRIT The inspiring story of a soldier who survived the loss of his comrades, faced adversity and overcome it all Dedication This book is dedicated to all those who lost their lives at Warrenpoint, Northern Ireland, on 27 August 1979, and to their families. ANDREWS, Corporal Nicholas J. (2 Para)—aged 24 BARNES, Private Gary I. (2 Para)—aged 18 BEARD, Warrant Officer Walter (2 Para)—aged 31 BLAIR, Lieutenant Colonel David (Queen’s Own Highlanders)—aged 40 BLAIR, Private Donald F. (2 Para)—aged 23 DUNN, Private Raymond (2 Para)—aged 20 ENGLAND, Private Robert N. (2 Para)—aged 23 FURSMAN, Major Peter (2 Para)—aged 35 GILES, Corporal John C. (2 Para)—aged 22 IRELAND, Lance Corporal Chris G. (2 Para)—aged 25 JONES, Private Jeffrey A. (2 Para)—aged 18 JONES, Corporal Leonard (2 Para)—aged 26 JONES, Private Robert D.V. (2 Para)—aged 18 MacLEOD, Lance Corporal Victor (Queen’s Own Highlanders)—aged 24 ROGERS, Sergeant Ian A. (2 Para)—aged 31 VANCE, Private Thomas R. (2 Para)—aged 23 WOOD, Private Anthony G. (2 Para)—aged 19 WOODS, Private Michael (2 Para)—aged 18 Foreword Prologue Chapter One The Terror of Toton Chapter Two The Maroon Machine Chapter Three Knowledge Dispels Fear Chapter Four Warrenpoint Chapter Five Broken Chapter Six Moving On Chapter Seven A Leap of Faith Chapter Eight Red Devil Chapter Nine The Wrong Way Round Chapter Ten Preparing for the Race Chapter Eleven The Lonely Sea and the Sky Chapter Twelve The Southern Ocean Chapter Thirteen Sea Change Chapter Fourteen Not Forgotten Chapter Fifteen The Silver Screen Acknowledgements Copyright About the Publisher

It was a quiet, sunny day in the early part of the 1960s when my mum received the phone call.

‘Joan speaking,’ she said.

It was a neighbour, Marjorie, who lived next to our comfortable house in Toton, a suburb of Nottingham.

‘Er, Joan,’ she said. ‘Don’t panic or anything. Just nip upstairs and quietly go into the back bedroom.’

‘Why? What’s wrong?’

‘Just be quick, eh?’

So my mum put down the phone, went upstairs and opened the door to one of the bedrooms. And there she saw me. Somehow I had managed to open the window, climb into the frame, then hold onto the window itself and swing outside. I was rocking to and fro with a big smile on my face. The only problem was that I was 3 years old, and my makeshift playground was twenty feet up in the air with nothing to break my fall. Quite how Mum managed to hold it together enough to gather me in her arms and pull me back inside to safety, I don’t know. But I guess, with antics like that, it’s no surprise that my family started to call me the Terror of Toton.

That wasn’t the only time I gave my mum cause to catch her breath. Far from it, if the stories I’ve heard about my earliest years are true. Our house was in a cul-de-sac about 100 metres from the busy A52. This major road linked the north Midlands with the east of England and, even in those days, it was full of lorries and other fast-moving traffic. Not the ideal place for a toddler to go walkabout, but that’s just what I did, not long after the window incident. The Terror of Toton was found wandering across this road on the back of his treasured hobbyhorse, oblivious to the danger he was in.

Perhaps it’s a bit too much to say that as a toddler I was a free spirit. Perhaps all toddlers are free spirits, and in many ways I was no different from a lot of children. As for so many little boys, my Action Man and soldiers were always my favourite toys. And I certainly remember being taken to a playgroup in a big Victorian building and spending the whole time sitting by the exit, waiting to be collected, while all the other kids happily played nursery games. I hated being cooped up inside—I just wanted to be out in the fresh air, left to my own devices. No doubt my tendency to swing from first-floor windows or venture alone across busy main roads was a source of some anxiety for my mum and dad, but I sometimes wonder if I’ve changed so much since those very early years.

Ours was a large family. When I was born, on 25 March 1961, my oldest brother John was already 18, my oldest sister Jill 16, and my youngest sister Rosalind was 8. John and Jill were more like an uncle and an aunt than a brother and sister, and I probably couldn’t help but be inspired by them in some way. Jill became a midwife and John a policeman—both professions in which they served the community, just as I would aim to do when the time came for me to make my own choice of career.

My dad, Matt, worked for the TV company Rediffusion as an area manager and general troubleshooter. It was a good job and it meant we lived comfortably in a large, four-bedroomed house, had a nice car, and my older brother and sisters went away to private schools. But in 1965, just as my earliest memories start to take shape, disaster hit our happy, well-to-do family. Dad suffered a massive heart attack and stroke. He died, leaving Mum widowed with a 4-year-old boy and a 12-year-old girl to look after. So I barely remember my father, and those memories I do have come more from creased old black and white photographs and from what other people have told me about him than anything else.

Читать дальше