By the time Lily was born, Papa was working in the stables of the Swan Hotel in the town square, and the family was living in a cramped house in North Street, which stood directly opposite Sis’s parents’ house in South Street. The first few years of Lily’s life were spent in the shadow of a series of Colvin crises, which taxed Sis until she was red in the face with exhaustion and despair. Sis’s father was becoming increasingly demented (he would report Papa for abusing his horses but the inspectors always found them healthy and grazing happily, as round as barrels). Sis’s youngest brother, Arthur, her mother’s favourite, had not survived the war. (12 per cent of those who fought on the western front were killed, rising to 27 per cent of officers; Duns alone lost seventy-five men to the war.) Her mother, engulfed by grief, had taken to guzzling pitchers of whisky to numb the pain. She had also contracted dropsy and swollen to gargantuan proportions. She rarely rose from her bed. Those brothers still living at home, Jock and Jim, were indolent and disinclined to help. And then, in March 1918, Sis’s younger sister died in childbirth. Her daughter was also named Lily, but when it became apparent that nobody could or would care for her but Sis, the child was deposited at North Street and renamed Rose to avoid confusion.

If these burdens took their toll on Sis, she took them out on her own family. As a result Papa spent more time at the bar of the Swan, which angered Sis further, and the children learned never to approach their mother when she was in a rage or to contradict her even when they knew her to be wrong. Later Lily would write in the patchy beginnings of her memoirs, which she called No Silver Spoon , ‘Mother had a strong character … life had been hard for her as a child. Her environment hadn’t broken her as it might have done but had given her determination and a strong will, so it was she who set the rules, we were taught the difference between right and wrong, and if we broke the rules we were punished.’

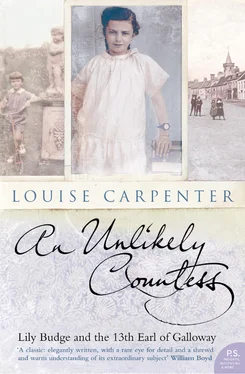

The Miller girls, always impeccably dressed and groomed, with laundered smocks and over-combed hair, were as temperamentally different as their parents. In personality Lily was closer to Rose, a fiery, hot-headed girl quick to lose her temper. Rose would be the first to challenge Sis and the first to escape Duns, running off to Edinburgh at the age of sixteen. It was Rose with whom Lily clashed. Each night Etta would look on, dismayed, as her sisters tugged crossly at the oil lamp Sis had placed between them. Etta was far more bovine, round and plump and compliant, the prettiest of the three; a simple and uncomplicated child with no inclination to gaze to the horizon. Lily, with her odd, bony little face, bulging eyes, and pale knobbly legs protruding from her skirt like matchsticks, was the bridge between Rose and Etta. She possessed Etta’s gentleness and Rose’s bravado and courage. She was quixotic in attitude and agile in her movements – quite the opposite of the stolid Etta – and liked to dance and spin around, tossing her head so that her bunches twirled and bobbed about her ears. It was a show put on for anybody who would look, but the best audience was always Papa. Really, though, despite her love of dancing – ‘what rubbish,’ Sis would mutter – Lily learned early on that the most effective way of winning affection and love was by saying what people wanted to hear, and in this her acting skills came in useful.

Just before Lily’s fifth birthday, Papa was offered a position on a private estate in Ayrshire looking after hunters and racehorses, accommodation included. If ever there was a chance for Sis to slip the Colvin leash, it was now. The family packed up their possessions, piled them onto Papa’s horse and cart and set off for a new, independent life. Lily was devastated. It meant leaving behind her best friend, a wiry haired old woman called Hannah who lived in the bottom half of their council house. Hannah was an Irish immigrant, an agricultural labourer of the sort known in the lowlands as a bondager, and every night she was to be found in her bonnet and flounce sleeves, drunk in the town square, lashing out with her wizened legs at the local constable. She was, Lily later recalled, ‘very special. I have never met anyone like her since.’ It was life without Hannah, rather than leaving Duns, that Lily found intolerable. The old woman had fed her stories of taking to the road in a gypsy caravan, ‘with a horse to drive like a pedlarrman [ sic ], just the two of us,’ and one day went a step further, rasping hotly in the child’s ear ‘take care of those hands – one day you will become a great lady’.

Hannah might have been filling Lily’s head with bunkum, but it was to have one effect: it confirmed what Lily had already begun to feel, that she was different and wanted to escape. But climbing on Papa’s cart, squashed in next to Sis and her sisters, did not have the same appeal as bumping along in Hannah’s imaginary caravan.

Lily need not have worried. Within eighteen months the Millers were back. Annie Colvin’s health had taken a turn for the worst and, when duty called, Sis could not help but come running. Annie Colvin died on 19 December 1922, when Lily was eight years old. When the undertakers arrived, they found the corpse so heavy and large that it could not be carried down the staircase. Eventually the body was placed in a secure box and lowered to the pavement using a rope pulley. Given the location of the two houses and the fact that the horrible business must have attracted a crowd, it is likely that Lily witnessed her grandmother’s final indignity, lying on the pavement in her makeshift coffin.

The first time Lily felt what life might be like free of the Millers en masse , was at Duns Primary School, an unprepossessing low stone building close to North Street. The school was hardly a hotbed of self-expression. Once a week, for instance, the older girls were herded into line and marched over to Berwickshire High School so they could learn to cook for their future husbands and employers. There were also lessons in laundry and needlework, washing and ironing, hemming and patching, all practised on squares of white cotton and flannel. (At the end of the nineteenth century a series of codes was passed – by a government of men – that made it clear to schools that their grants would be adversely affected if such subjects were not included. Too many men had been rejected from fighting in the Boer War on medical grounds, and if the British male was puny and unhealthy, it seemed his wife’s cooking was to blame.) But compared to the atmosphere of chaos control and pleasure policing at North Street, school promised much. Lily did not warm to many of the spinster teachers – they were starchy and sharp-tongued and made her cry by thwacking maps with pointers and asking her questions she could not answer – but Mr Thomson, the headmaster, was heaven itself.

Danny Thomson was a strict, sprightly man who wore orange tweed plus-fours and liked to show the children clippings of the hybrid plants he grew in his garden. He taught academic subjects, but was especially keen on encouraging the dramatic arts. Although tone deaf, he was keen to involve his charges in the Borders Festival, a competition of performing arts in which many of the region’s schools took part. By 1928, after a string of victories that saw him banging on the school piano more fiercely than ever, in the interests of fairness, Duns Primary was asked not to enter. It was under Mr Thomson’s nurturing eye that Lily learned to tap dance. ‘I had been blessed with a good singing voice,’ she declared in later life, ‘a pair of light dancing feet and a certain ability to act.’ She became so good that Mr Thomson soon suggested she dance in shoes made for the job. Perhaps her mother would buy her some? Sis would no more pay for such frippery than she would prop up the bar at the Swan. Lily could go straight back to Mr Thomson and tell him what to do with such a ridiculous suggestion. Mr Thomson, keener than ever to ensure his star continued to sparkle, was not easily dissuaded. Shortly afterwards, he presented Lily with a pair of shoes he had found himself, cast-offs but tap shoes nonetheless. Lily ran home to North Street suffused with joy. The tap shoes entered through the front door and left through the window.

Читать дальше