Rain or shine, the 1,100 sanitation workers of Memphis collected what amounted to 2,500 tons of garbage a day. This all-male, exclusively African-American staff worked six days a week with one 15-minute break for lunch and no routine access to bathroom facilities. Their pay was based on their garbage routes, not their hours worked, so there was no overtime compensation when the days ran long. Workers supplied their own clothing and gloves, toted rain-saturated garbage in leaky tubs supplied by the city, and had no place to shower or to change out of soiled clothes before returning home. Even though the men worked full-time, their earnings failed to lift their families from poverty. To make ends meet, many found extra jobs, paid for groceries with government-sponsored food stamps, lived in low-income housing projects, and made use of items scavenged during their garbage runs.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks, who made up almost 40 percent of the city’s population, performed the backbreaking labor. Bosses expected to be addressed as “sir.” Workers endured being called “boy,” regardless of their ages. Whites presumed to know what was best for “our Negroes,” and blacks tolerated poor treatment for fear of losing their jobs, or worse. City officials had no motivation to recognize the fledgling labor union that sought to protect the workers and to advocate for their rights. As a result, employees “acted like they were working on a plantation, doing what the master said,” recalled sanitation worker Clinton Burrows.

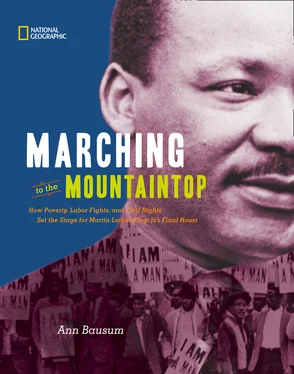

Memphis residents, or Memphians, called their sanitation workers garbagemen, walking buzzards, and tub toters, a name that reflected the washtubs they used for ferrying garbage from backyard storage barrels to city trucks. Workers (above, R. J. Sanders) balanced the large tubs on their heads or pushed them in three-wheeled carts.

Garbage collectors faced back injuries and other strains because of the physical demands of the work, and they fretted about the use of unsafe equipment. Willie Crain’s truck had been purchased on the cheap in 1957 at a time when Henry Loeb ran the department of public works. By 1968, when Loeb returned to public office as the newly elected Memphis mayor, the city had begun replacing the old trucks. Two of the vehicles, including Crain’s truck, had been retrofitted with a makeshift motor after the unit’s trash-compacting engine had worn out. As best as anyone could figure after the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, a loose shovel had fallen into the wiring for the replacement motor and had accidentally triggered the reversal of the trash compactor.

Like those of other sanitation workers, the families of Cole and Walker managed paycheck to paycheck, leaving no reserves for emergencies. Their jobs came without the benefits of life insurance or a guarantee of support in the case of work-related injury or death. Mayor Loeb honored the victims by lowering public flags to half-mast, but he offered scant assistance to their survivors. The city contributed $500 toward the men’s $900 funerals and paid out an extra month’s wages to Cole’s widow and the widow of Walker (who was pregnant).

The deaths of Cole and Walker wrapped up a particularly bad week for African Americans employed at the department of public works. This unit handled garbage collection, street repairs, and other city maintenance. On January 30, two days before the sanitation-worker fatalities, 21 members of the sewer and drainage division had been sent home with only two hours of “show-up pay” because of bad weather. The previous public works director had kept staff employed regardless of the weather, but Mayor Loeb had ordered Charles Blackburn, his new director, to return to Loeb’s old rainy-day policy from the 1950s. In a climate where rain fell frequently, workers lost their ability to predict their income. “That’s when we commenced starving,” explained road worker Ed Gillis.

Street workers turned to Thomas Oliver Jones for help. T. O. Jones was among 33 sanitation workers who had started a strike in 1963 and lost their jobs. When officials were pressured to rehire the workers, Jones refused to rejoin the force. Over time he established a fledgling union for public works employees and gained recognition for his small group by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, better known as AFSCME. Jones’s group called itself Local 1733 in honor of the 33 men fired during the 1963 strike. Jones tried to lead another walkout in 1966. This time 500 workers agreed to strike, but the work stoppage collapsed after a local judge declared the strike illegal. “All city employees may not strike for any purpose whatsoever,” the judge declared. This injunction, or prohibition against striking, had never been challenged in court, so it remained in force and discouraged further strikes. Nonetheless, Jones continued to quietly recruit members for Local 1733 and became its unofficial spokesperson.

“THERE wasn’t too much opportunity for a black man at that time. Really wasn’t no other jobs hardly to be found. I was at a point I had to take what I could get.”

Taylor Rogers, who became a Memphis sanitation worker about 1959

Jones raised the men’s rainy-day concerns with Charles Blackburn and left the meeting thinking the public works director had agreed to pay the 21 men their missing wages. Blackburn said he would reconsider the rainy-day policy, too, and, within a few days, he instructed supervisors to try to keep everyone fully employed regardless of the weather. During that same period, Panfilo Julius Ciampa, field director for Washington, D.C.-based AFSCME, visited Memphis. Jones arranged for his union contact to meet the new public works director on February 1. P. J. Ciampa learned that Blackburn was a personal friend of the newly elected mayor and had gained appointment to the job after an unrelated career in insurance work. He would later describe Blackburn as “a guy who didn’t know a sanitation truck from a wheelbarrow.”

By 1968 the city of Memphis had replaced most of its garbage trucks with a rear-loading model (above, carrying unidentified workers). Echol Cole and Robert Walker died in an older side-loading vehicle nicknamed the wiener barrel because of its rounded shape. Their fatalities followed the deaths of two other sanitation workers during a 1964 truck rollover accident.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks performed the backbreaking labor.

Their afternoon meeting took place shortly before

Willie Crain’s truck began crushing two sanitation workers to death. Jones learned of the accident almost immediately. As he drove back from taking Ciampa to the Memphis airport, Jones followed a hunch that trouble was brewing and pursued an emergency public works vehicle that turned out to be racing toward the reported accident. Events snowballed as the news spread. Surviving workers knew they could just as easily have lost their own lives. They grew offended when the city didn’t cover the full costs of burying the victims. They fretted over the potential for lost wages during bad weather. They worried about how to survive on the money they earned even at full employment. And they fumed when the 21 workers opened their pay envelopes the following week and discovered no boost in pay for the rainy day of January 30.

Something snapped—or perhaps ignited—under the weight of these pressures in a system run with that plantation-style mind-set. In theory, slavery had ended 100 years earlier, but blacks in Memphis during 1968 had more in common with African-American slaves who had worked the region’s cotton fields than with the whites who ran Memphis businesses, served in city government, and covered the local news. Even poor whites, thanks to decades of segregated southern living, focused more attention on their racial superiority over blacks than the common interests they and blacks could have pursued through unions for higher wages and better working conditions. Poverty, racial isolation, and a history of voter intimidation left blacks underrepresented and their needs ignored.

Читать дальше