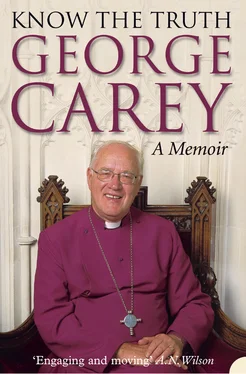

Even as a youngster I could tell what that commitment to Christ did for my mother and father. It changed them both, and gave them a great thirst to know more not only about the Christian faith, but about how to apply that knowledge to life around them. The limited education my father had received made it impossible for him to do anything other than lowly jobs, and soon after his conversion he became a porter at Rush Green Hospital in Romford, where he made a deep impact on the lives of many patients through his Christian goodness and kind words.

As for me, my learning too continued. My work at the London Electricity Board did not tax me, and I was eager to move on. The opportunity came when, not long before my eighteenth birthday, I received a letter informing me that I was due for my National Service call-up. I was delighted. It was time for me to move from my secure home, and I was ready to go.

‘Why couldn’t Quirrell touch me?’

‘Your mother died to save you. If there is one thing Voldemort cannot understand it is love … love as powerful as your mother’s leaves its own mark. Not a visible sign … but to have been loved so deeply, even though the person who loved us is gone, will give us some protection forever.’

J.K. Rowling , Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

WITH A YOUTHFUL IMAGINATION fired by Mr Kennedy’s stories of the Royal Navy, and fed by my experience in the Sea Cadets, my preference was to do my National Service in the navy. Unfortunately, the Royal Navy did not accept conscripts at that time, so it had to be the Royal Air Force. As it turned out I was not to be disappointed in the slightest. For a young man eager to explore life and widen his horizons, the Air Force suited me down to the ground.

First came a week of ‘kitting out’ at RAF Cardington, where hundreds of dazed and subdued eighteen-year-olds gathered to be allocated to billets, receive severe haircuts and don the blue uniform of the youngest service. Pit-Pat’s final advice to me the previous day seemed particularly daunting: ‘George, you must disclose that you are a Christian right from the start. Don’t be ashamed of your faith. When lights go out, kneel by your bed and say your prayers.’ This had seemed easy enough to agree to when in church, but I confess that as I surveyed the crowded billet on my first evening, with the good-natured banter of high-spirited young men all around me, my resolve wavered. Nevertheless, taking a deep breath, I knelt and spent several minutes in prayer.

The reaction was interesting. First there was a quietening-down of voices as everyone realised I was praying and, unusually courteously, gave me space for prayer. The second reaction – clearly predicted by Pit-Pat – was that it marked me out as someone who took his faith seriously. The following day at least six young men in the billet took me aside and declared that they were practising Christians. By the end of the second day we were told of a SASRA (Soldiers and Sailors Scripture Readers’ Association) Bible-study meeting that evening. SASRA was particularly favoured by nonconformist and evangelical Christians, and throughout my National Service I found it a wonderful source of fellowship and support.

I never found that my practice of public praying, which I kept going for a great deal of my time in the Air Force, limited or negatively affected my relationships with other servicemen. To be sure, there were often jokes when I knelt down to pray. There were several times when things were thrown at me, and once my left boot was stolen while I was on my knees – just minutes before an inspection. Somehow I managed to keep to attention with one boot on and one off as the officer advanced through the billet.

Years later, in fact just a few weeks before I retired, I was touched to receive a letter from a Mr Michael Moran, who wrote to my secretary at Lambeth Palace:

Dear Sir,

Are you able to tell me whether George Carey spent the early years of his National Service at the basic training camp at RAF Cardington? When I was there at that time I was deeply impressed (and this has remained with me ever since) by the devotion and courage of an eighteen-year-old named George who knelt to pray at the side of his barrack-room bed. At no time in the following two years did I see anyone else show such evidence of his faith.

I was rather uncomfortable to receive such praise, because I did not kneel down to impress people by my courage, or to be the odd man out. In fact, I shrank from doing so. I did it simply because I felt Pit-Pat was absolutely right: if prayer is important, and if one is in a communal setting with no private place to pray, one ought not to be ashamed or embarrassed to be known as someone who loves God and worships Him. Later in life I would put the issue as a question to others: ‘Muslims aren’t ashamed to pray publicly, so why should Christians feel embarrassed? If it is a good way of praying when one is alone, why should we be ashamed of acknowledging a relationship with God when we are with others?’

The relative calm of the kitting-out week was followed by eight weeks’ hard square-bashing at West Kirby, near Liverpool. To this day, while I am left with many questions about the psychology behind the tyrannising and brutal attitude of the Platoon Leaders and Sergeants, there can be little dispute that it is a highly efficient way of moulding young men into effective members of a military unit. For eight weeks we were terrorised by screaming NCOs who told us in unambiguous terms that we were the lowest forms of life ever to appear on earth: ‘You are a turd of unspeakable putrefaction’, ‘a cretin with an IQ lower than a tadpole’, ‘You are the scum of the earth! What are you? Repeat it after me: the scum of the earth’, ‘You are hopeless, hopeless, hopeless.’

The verbal ingenuity of some descriptions was rehearsed in the billet long into the evening, as we sympathised with victims or rejoiced at the misfortune of a rival platoon. There were times when I too became the object of the Squad Corporal’s wrath. ‘Carey, you little bleeder!’ he screamed into my face, his saliva making my eyes water, ‘I am about to tear your ****ing left arm off and intend to beat your ****ing ’ead in with the bloody end, until your brains – if you have any – are scattered far and wide.’ Imagine my disappointment when I discovered later that this threat was far from original, and was in fact a tried and trusty favourite of that particular NCO.

I was able to gauge attitudes to the Church from the viewpoint of the ordinary conscript. The vast majority of my ‘mates’ had no contact with institutional religion. Although most of them, deep down, had faith, few of them had the ability to convert it into anything of relevance. They were not, on the whole, helped by the Chaplains, who held officer rank and talked down to the conscripted men. We all had to go to compulsory religious classes, and I can only say that from a Christian point of view these were something to be endured rather than enjoyed. The talks were usually moralistic, and the most embarrassing were about sex, a subject on which the Chaplains were definitely out of touch with the earthy culture of working-class people. I remember asking myself: ‘Why are they so shy about talking about the subject where they are expert? About the existence of God, about spirituality and prayer, about Jesus Christ and His way?’

Even more frustrating to me was the fact that I never saw a Chaplain visiting the men, either in the mess or in the billets. Far more effective was the ordinary ‘bloke’ from SASRA, who at least had the courage to meet the men where they were. Church parades were no different. The hymns were sung indifferently, and the sermons went over the heads of all. I was often embarrassed by the effete way services were conducted, and felt that overall they did more harm than good to the Church.

Читать дальше